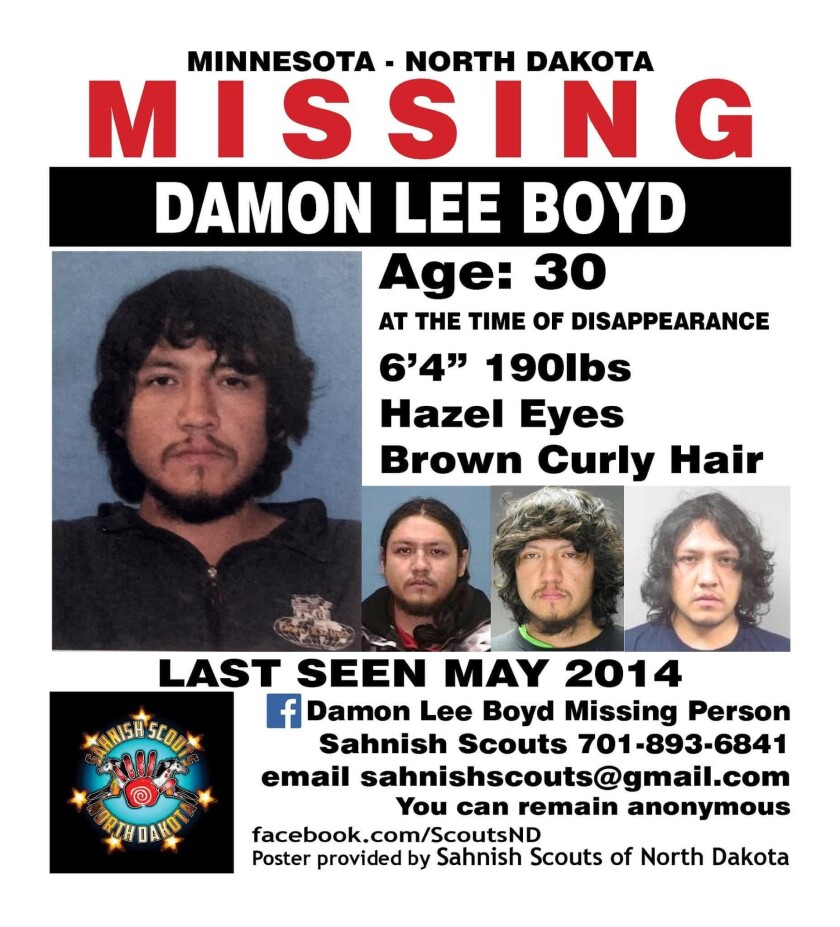

MINNESOTA — Lissa Yellow Bird Chase is asked for guidance or assistance with a new Indigenous person's disappearance almost every day, but she never forgets those who remain missing, including Damon Lee Boyd, who hasn't been seen for a decade.

"That's like my grandson," Yellow Bird Chase told the Grand Forks Herald.

ADVERTISEMENT

Boyd, an enrolled member of the Leech Lake Band of Ojibwe, was reportedly seen in the Grand Forks area on April 30, 2014, shortly before he vanished, seemingly without a trace. He was something of a transient, Yellow Bird Chase said, but had a room at his grandfather's home in S. Lake, Minnesota, and also spent time in Bemidji.

Damon Boyd was raised by his grandfather, Louis Boyd, whom Yellow Bird Chase knew as her brother, though they're not biologically related. He died in April 2024, just shy of 10 years after his grandson's disappearance.

"His last wish was to find Damon," Yellow Bird Chase said. "We'll be reviving those efforts this year."

As founder of the Sahnish Scouts of North Dakota, an organization that publicizes missing persons cases and searches for the missing, Yellow Bird Chase and her cadaver dogs have held many searches for Boyd throughout the years, but her work is not over.

She plans to do more research to prepare for additional search efforts in the Bemidji area later this year — keeping Boyd in mind, but also the others who are missing: Jeremy Jourdain and Nevaeh Kingbird.

By becoming Boyd's legal guardian, Yellow Bird Chase was able to access medical records that confirmed he'd been in the emergency room at Bemidji's Sanford Medical Center shortly before he disappeared. She knew to check there because Boyd was commonly hospitalized for his severe withdrawals.

"Because of his addiction, he would drink, and then coming down from that, he would always need medical assistance," Yellow Bird Chase said. "So he was a regular in the ER, and I was able to track him. We’re talking maybe a minimum of two visits a week.”

ADVERTISEMENT

Boyd's alcoholism ran deep, she said; he was born with fetal alcohol syndrome. He had been seeking treatment at Douglas Place in East Grand Forks in the days leading up to his disappearance.

The issue of Missing and Murdered Indigenous Peoples is so pervasive that it, at times, results in a number of disappearances within one family — including Yellow Bird Chase's and Boyd's.

Boyd's father — whose name Yellow Bird Chase didn't remember, and the Herald was unable to find — vanished and was found deceased, underneath a fish house, within years of his son's own disappearance, Yellow Bird Chase said.

Authorities said he crawled under the structure and died there, but while he was missing, Damon Boyd's mother — Dawn Boyd — was suspected of involvement. Yellow Bird Chase said the woman had nothing to do with it, and died not long after in a vehicle crash caused by a drunk driver.

"There's a lot of tragedy there," she said.

Yellow Bird Chase believes addiction is the most common factor that makes Indigenous people vulnerable to these tragedies. The second is homelessness, followed by domestic violence and so on — and they're all connected, she said.

'It's our own people'

Another issue, Yellow Bird Chase said, is that Indigenous people often fail to understand, or refuse to admit, that these disappearances can't always be attributed to the creepy, white farmer down the road or migrant oil field workers.

ADVERTISEMENT

"It’s not ... the propaganda that’s been put out there," she said. "Maybe it was in yesteryear, but it’s our own people killing our own people. And we have to face that fact or we’re never going to get past it. We’re never going to make a difference."

She acknowledges that this can be difficult though, and even dangerous.

As sovereign nations that govern themselves, tribal communities are very close-knit, seeing each other as family. But when tribal affiliation is everything, tribal politics can spread throughout everything.

"If you make waves, you will lose a job, you will lose housing, they will do everything to target you," she said. "And then comes the violence."

In some instances, people may end up in the same position as the loved one they were attempting to seek justice for.

For others, it's just not worth it — especially if the suspected perpetrator is someone they know well. Yellow Bird Chase has had parents tell her they don't see a point in pursuing justice for their loved one because it won't bring them back; it will just cause another person they love to suffer.

"So just let (them) go ahead and find other victims?" she said. "And usually they do, because that behavior doesn't resolve itself."

ADVERTISEMENT

Yellow Bird Chase does admit that her and Louis Boyd's own desires for justice lessened as more and more time passed.

"We just want Damon back," she said. "We just want to lay him next to his mother."

Completely cold

It has been close to 11 years since Boyd disappeared.

"Damon's case is completely cold," Yellow Bird Chase said. "There's nobody inquiring."

Nobody, that is, except her.

Yellow Bird Chase is from the Fort Berthold Reservation, with lineal ties to the Standing Rock Sioux. She saw a need for people like her, with no government or law enforcement affiliation, to assist with locating people who disappear on tribal lands reservations. The need became especially apparent when a young, white man disappeared from the reservation where she lived, and nobody seemed to do much about it.

"(Kristopher 'KC' Clarke's murder was) one of the biggest cases ever, and it almost slid under the rug because of politics," Yellow Bird Chase said.

ADVERTISEMENT

The disappearance, which she believes was ignored because it occurred on the then-tribal chairman's property, appeared to mirror how people treat the disappearances of Indigenous people off of their reservations.

"Now, a young, white, male oil field worker comes to the rez, and he’s treated like we are off-rez," Yellow Bird Chase said.

Knowing that if her own child went missing, she would want someone to step up, she decided to be that person.

Clarke's remains were never found, but many other questions were answered. A business rival, James Henrikson, was found responsible for hiring someone to kill Clarke. Timothy Suckow was paid $20,000 to carry out that murder, as well as another, according to reporting by Reuters.

In 2013, a year after Clarke's disappearance, Yellow Bird Chase founded the Sahnish Scouts of North Dakota. She has made it her life's work to search for her missing and murdered people, and teach others how to do the same.

She believes people trust her because she doesn't care about the politics or power dynamics involved; she only cares about finding out what happened and bringing people home so their loved ones can start the grieving process.

"We’re the boots on the ground," Yellow Bird Chase said of her team. "We’re the ones who go knocking on doors. We’re the ones who are uninhibited and unafraid to go ask people hard questions — and get the answers.”

ADVERTISEMENT

She believes her practices have made waves, and she's very, very proud to see that others are catching on.

Yellow Bird Chase implores those who hear or see something to say something, because there are are a lot of people who have information but hold back from reporting it.