CHAFFEE, N.D. — Becky Dooley was a versatile athlete growing up in the rural Cass County community of Chaffee. But sports, especially women’s sports, were still in their infancy in the early 1970s.

“You have to realize that North Dakota had many small schools and Chaffee was a very small school, probably 150 students K through 12, and so there weren't a lot of girls that wanted to play sports,” Dooley told the Sports Time Machine recently.

ADVERTISEMENT

In the spring of 1974, Dooley stepped to the plate as a senior on the school’s baseball team.

Let’s rewind more than 50 years ago and follow Dooley’s footsteps as North Dakota's first girl to play on a boys high school sports team.

She played basketball, but as she said, “we barely had six players to play.” She played summer softball, playing in the 1973 state women’s slowpitch championship game. She competed in track, even though there was not a fully assembled girls team. She kept score for the boys basketball team and at home, she was the oldest of eight children.

“It's a farming community and the neighbors would get together and we would play baseball and we’d play football, and you know it was mixed girls and boys,” she recalled. “Whoever was in the neighborhood to play.”

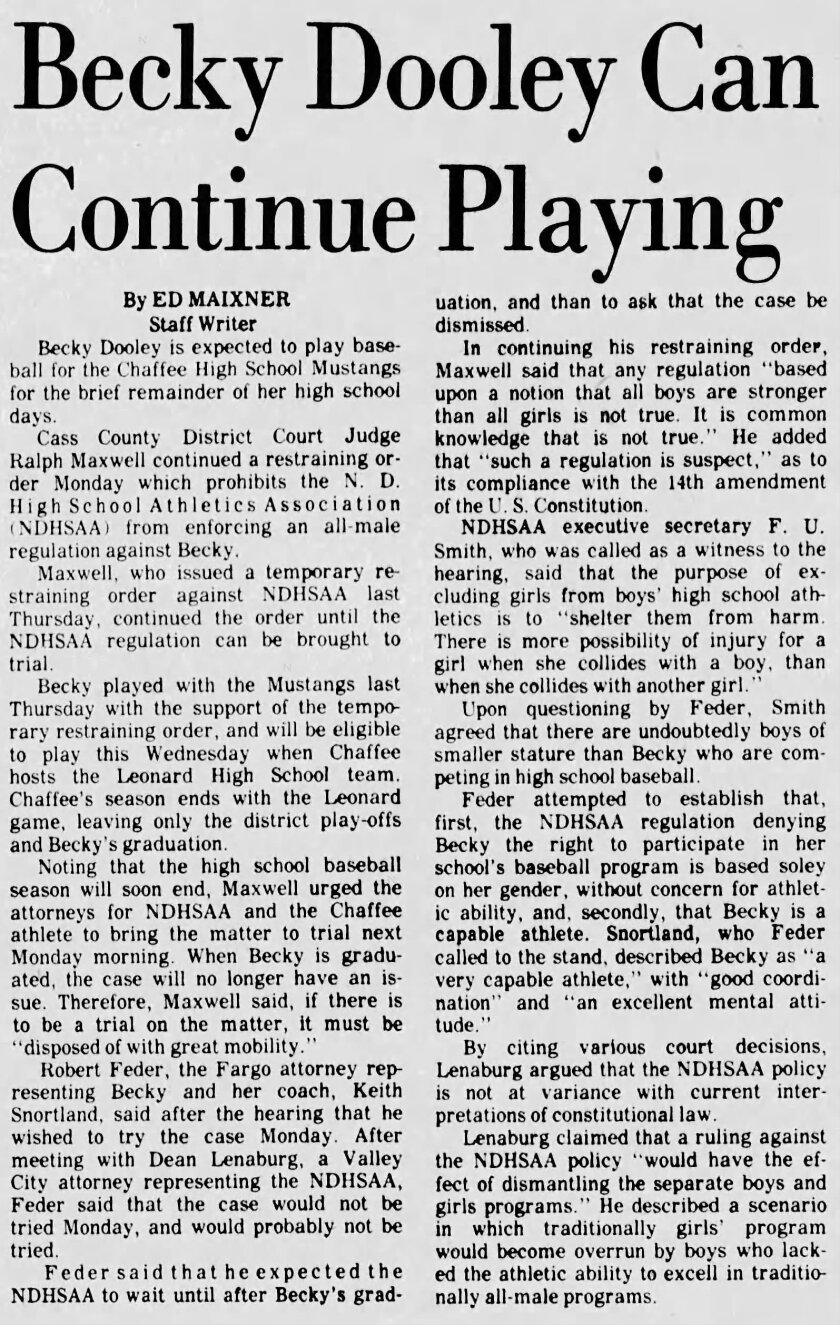

It gave her the idea to ask Chaffee baseball coach Keith Snortland if she could play. After all, she had brothers playing, too. But it would require more than just inserting her in the lineup. In 1974, the North Dakota High School Athletic Association did not allow girls to play on boys sports teams.

So Dooley took legal action. Fargo attorney Robert Feder took the case pro bono. Feder, who would later play a large role in the passage of the state’s human rights act in the early 1980s , helped secure a temporary restraining order against the NDHSAA.

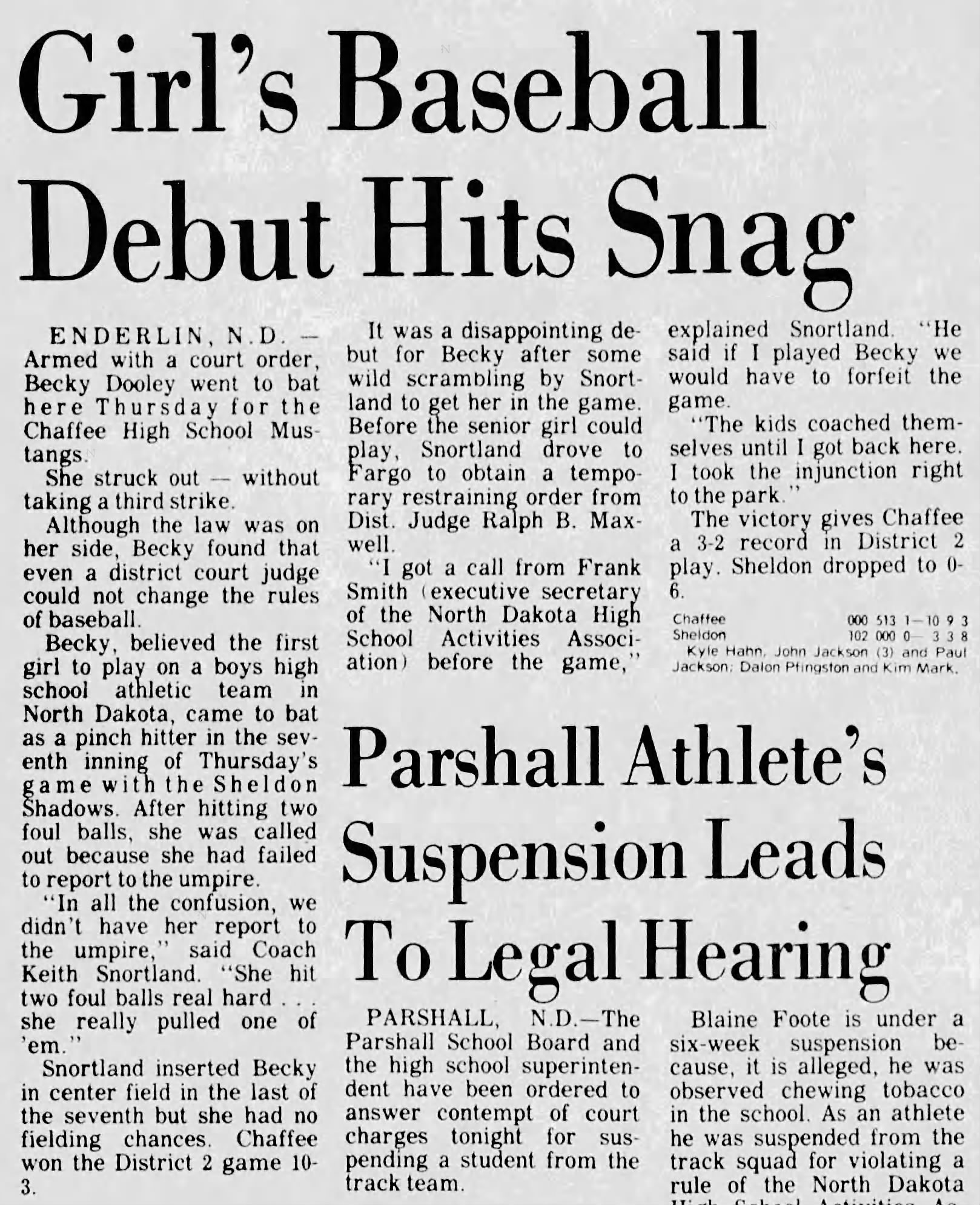

Snortland traveled those 40-some miles to Fargo on May 2, 1974 to secure the paperwork, arriving by the middle innings of a game against Sheldon.

ADVERTISEMENT

“He showed the other team [the paperwork] and he subbed me in to bat,” Dooley recalled of the game played in Enderlin. “I hit a foul ball to left field almost over the fence, but it was a foul ball and they pitched again, and I swung again and just slammed it way out there.”

The two foul blasts caught Sheldon’s attention. But there would be no third pitch after Sheldon’s coach made his plea.

“So my first up-to-bat, I had two good cuts, even though they were foul balls,” Dooley said. “I was automatically out because the coach, in the midst of all the excitement, forgot to go up to the ump and tell him my name and number for the substitution.”

Dooley doesn’t recall her first official hit, though she would finish the remainder of the season on the team. She had her share of getting on base, and though her teammates supported her, that wasn’t always reciprocated by the opposing teams.

“I remember getting hit by pitches and them trying to do brushback pitches, or pitch real hard and try to make you swing when you knew you weren't supposed to,” Dooley recalled. “They just made it difficult. It wasn’t easy when they pitched toward your head or toward your body instead of just going for the strike zone.”

Randy Rusch, a 1974 graduate of Leonard, remembers playing against Dooley.

“It can still picture her at bat,” said Rusch, who struck Dooley out in a May 22, 1974 game.

ADVERTISEMENT

Dooley and her teammates beat Leonard 5-2 that day. Dooley was 0 for 2 with a walk.

“It was obviously a novelty but we just kind of took it in stride,” he added. “It was long before the days of things like this were coming across in the world. It was small-town baseball.”

Dooley’s actions, however, made big-city headlines.

The Forum, Bismarck Tribune, Minneapolis Star and Fargo sports personality Jim Adelson and his “Sports Reel” carried her story. A Sports Illustrated edition from May 30, 1974 with the NBA's John Havlicek and Kareem Abdul-Jabbar on the cover, a blurb about Dooley's efforts appeared inside. Politicians and organizations wrote her letters of support.

“I didn't understand the scope at that time because all I wanted to do was play,” Dooley said. “I really didn't like the publicity. I didn't like the newspeople coming in and interviewing and making more out of it than it was.”

That’s all it was because it would take another decade for the NDHSAA to change its ruling for baseball and other contact sports.

“It really wasn't about making it for other girls to play — equal rights and all that. That really wasn't what it was all about, I just wanted to play and be part of a team,” she told the Sports Time Machine.

ADVERTISEMENT

In October 1974, the NDHSAA approved permission for schools to form teams of both sexes in non-contact, non-collision sports if the school does not provide separate teams for each sex.

However, North Dakota would follow an Illinois ruling that baseball is a collision sport.

More than 50 years later, the coach who retrieved that temporary restraining order is proud of his former player.

“It surprised a lot of people,” Snortland, now 75 and living in Fargo, told the Sports Time Machine. “She wasn’t expected to do anything, but she did a wonderful job.”

As for Dooley, she went on to have a successful basketball career under coach Collette Folstad at Concordia College in Moorhead before teaching in Floodwood, Minnesota. She then worked for an insurance company and moved to Iowa.

An outdoors enthusiast, she returned to Minnesota and got a job as a recreation therapist at the Minnesota Correctional Facility-Willow River/Moose Lake in 1991. Several positions later, she was named its warden in 2010 and she retired in 2017. She lives in Cloquet, Minnesota.

Her athletic background was the backbone of her career.

ADVERTISEMENT

“Sports is a lifelong activity that you can do and whether it was in the school system or in the prison system, it's to teach people healthy living, lifestyles and things to do.”