DULUTH — Laura Arneson and four friends reached the Arctic Ocean after canoeing 400 miles down Alaska’s Noatak River last July.

From the river mouth, their destination, the town of Kotzebue, was just visible across 4 miles of open ocean. They camped at the mouth and woke at 3:30 a.m. hoping for calm seas. Even at this uncomfortable hour, the sun sagged over the eastern horizon, never setting on the high Alaskan summer.

ADVERTISEMENT

The five young paddlers pushed off in two canoes into calm water. As land receded behind them, the waves got bigger. They were using collapsable Pakcanoes — portable canoes necessary for the bush plane flight to the river’s headwaters they’d taken weeks earlier.

“Pack boats are bendy,” Arneson said, “so you could feel them bending in half a little bit as the bow was going over the waves.”

Her nerves sparked as water began running in over the gunnels. Their last day on the water suddenly became the scariest of the 20-day trip that unfolded. "Surprisingly smooth,” Arneson said.

A 27-year-old medical school student at the University of Minnesota Duluth, Arneson grew up in Minneapolis and moved to the city in August 2023.

“I really fell in love with Duluth,” she said. “I’m hoping to be here. In residency, they might send me who knows where, but I’d really love to be back here.”

The Noatak River sources in the Brooks Range of northern Alaska, in Gates of the Arctic National Park, and flows 425 miles west-southwest to the Arctic Ocean. The river is unreachable by road and never strays beneath the Arctic Circle. One small, roadless community lies along its banks and is inhabited by Inupiaq people, or Alaskan Inuit, who live a traditional, mostly subsistence lifestyle based on fishing and caribou hunting.

Arneson’s group consisted of four women and one man. They’d become friends at YMCA Camp Menogyn, located off the Gunflint Trail and on the edge of the Boundary Waters Canoe Area Wilderness. The fivesome, who heard the Noatak was an excellent paddling river set in unparalleled wilderness, wanted an adventure together before their lives got too complicated.

ADVERTISEMENT

Camp Menogyn was where Arneson got into canoe tripping. When she was 18, she went on a 50-day paddle journey through Nunavut, Canada. She later guided for the camp. This coming summer, she is going to introduce her father to Boundary Waters canoe camping.

On July 10, with 1,500 pounds of gear and their canoes collapsed into bags, Arneson and company boarded a bush plane in Coldfoot, Alaska, and flew across the Brooks Range to a lake near the Noatak’s headwaters. The plane touched down on the lake, and the paddlers portaged through short willows to the upper reaches of the Noatak.

The first section flows through a gorgeous mountain valley. Small willow trees grow along the river. Above, the mountains climb, their flanks clad in short alpine plants. On the first day, they spotted 36 Dall sheep grazing the slopes.

Throughout the trip, they tallied six grizzly bears, including a mother and two cubs. Some people had advised them to carry a firearm, though.

“None of us are well-versed in guns,” Arneson said, “and we would have felt less safe with one.” They carried bear spray and were careful about cooking away from their tents and never saw a bear closer than a couple hundred yards.

Arneson was surprised to see many seals. "Super cute," she said. "They’ll pop their little heads up and look at you. They swim upriver from the ocean following salmon migration.”

The canoeists were hoping to see caribou, but the annual migration hadn’t started yet and they spied only a single caribou, along with a couple quintessential Arctic wildlife, the muskox. They also spotted two Arctic wolves and an ancient mammoth tusk emerging from an eroded riverbank.

ADVERTISEMENT

On most days some rain fell. Some days were chilly and rainy and temperatures never left the 40s, while others were sunny and in the 70s.

Early on, in the mountainous section of the river, Arneson’s group met two other paddling parties doing shorter trips. Later, the Noatak leaves the Brooks Range for rolling tundra flats, and they saw nobody for a week until they met an Inupiaq man living alone in a cabin next to the river, 50 miles upriver from the roadless village of Noatak. The man’s name was Ricky and he invited the paddlers into his cabin for dinner, feeding them pilot biscuits (also known as hardtack) and pickled beluga whale.

I’m pretty worried the Arctic isn’t going to be there in the way it is for very much longer.

“I feel like I got to know the land a lot better through the people,” Arneson said. “By paddling the river, by experiencing it, I felt I understood the people we met a little better.” Her favorite part of the trip was spending time with the Inupiaq, who repeatedly invited the canoeists into their riverside homes and kept them flush with fresh salmon steaks.

Arneson was surprised by dramatic signs of climate change caused by melting permafrost. Eighty percent of Alaska’s ground is permafrost, and its melting is destabilizing the land. “The tundra is falling apart,” Arneson said. “There were massive sinkholes in the ground. We passed a lot of chasms where you could hear the chunks falling.”

Inupiaq people in riverside Noatak village told her about how a cemetery holding victims of the 1918 Spanish flu pandemic, which devastated the Alaskan Inuit population, had recently slumped into the river.

The Inupiaq are more worried, Arneson said, about new mining, which they fear will hurt the fish and caribou populations that make up most of their diet. Despite the area being one of the last great wildernesses left on an increasingly exploited planet, mining companies are pushing for a new 211-mile road to the south of the Noatak. The private Ambler Road would cross Gates of the Arctic National Park to access copper, lead, silver, gold and zinc deposits.

Last year, the Biden administration blocked the road from crossing federal land.

ADVERTISEMENT

“(T)he road would have required over 3,000 stream crossings and would have impacted at risk wildlife populations, including sheefish (a type of large whitefish) and the already-declining Western Arctic caribou herd," read a Department of the Interior news release in June.

After the recent presidential election, however, stock prices for the company, Trilogy Metals, which would profit from the road, quickly doubled on speculation that the Trump administration will greenlight the road.

Arneson is committed to returning to the far north but admits it might be a few years while she contends with the grueling schedule of medical school followed by residency. For her coming career, she is pondering both family and emergency room medicine. Yet, she’s going back north as soon as she can.

“I’m pretty worried the Arctic isn’t going to be there in the way it is for very much longer,” she said, if climate change and mining development make it unrecognizable.

A photo caption of Laura Arneson and her group with canoes incorrectly stated what they are doing. They are shown wading and lining their canoes in shallows. It was updated at 10:27 a.m. Jan. 27. The News Tribune regrets the error.

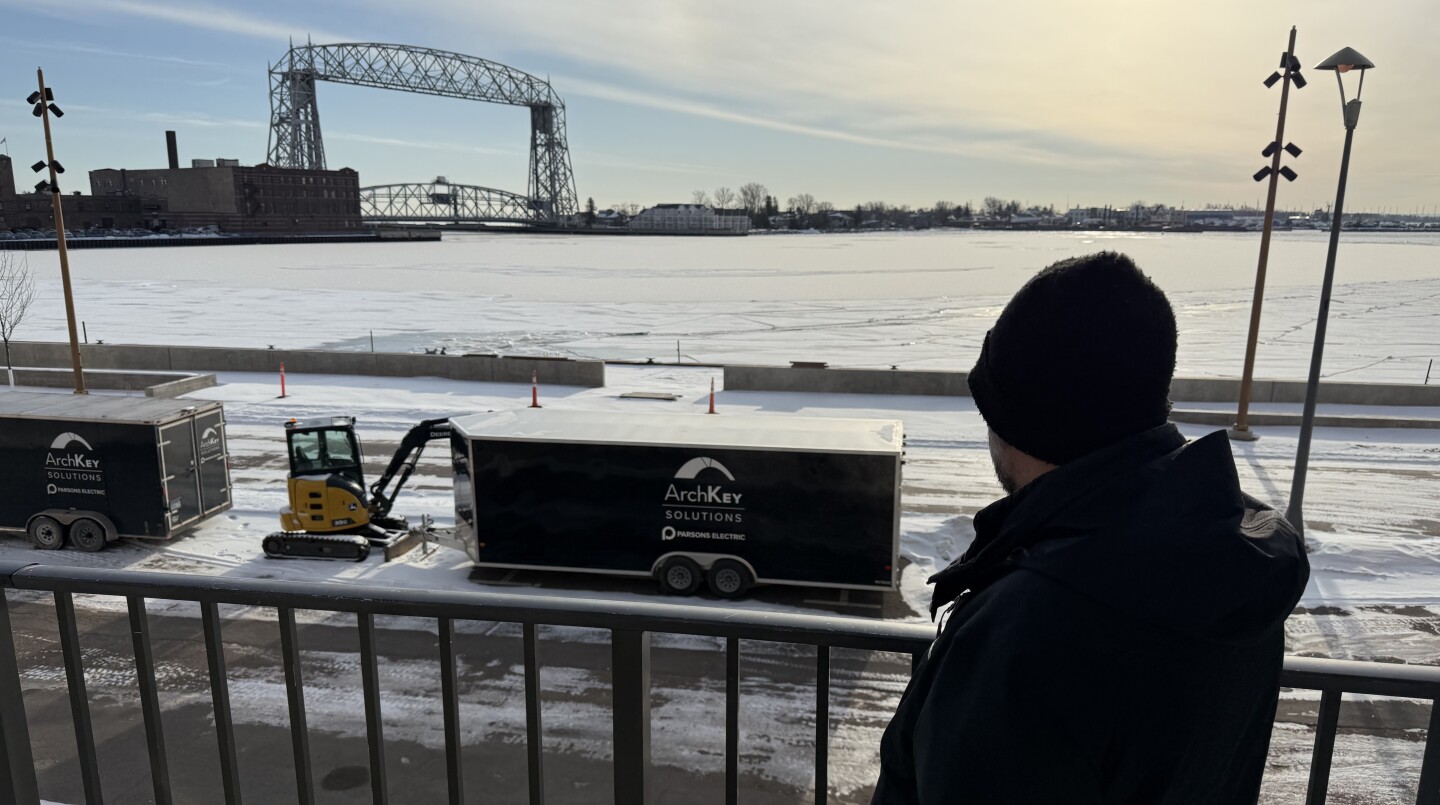

Laura Arneson spoke and showed slides to more than 100 people Jan. 16 at the Spirit Mountain Grand Avenue Chalet in Duluth. Her talk was part of the Duluth Climbers Coalition’s winter series, the Duluth Explorers Club, which highlights adventures done by locals and is not limited to climbing. Climbers Coalition co-founder David Pagel said the talks have been going for nine years and feature a wide variety of trips.

“We’ve visited both poles, climbed mountains from Kilimanjaro to Mount Everest, dived Mexican caves and Lake Superior shipwrecks, paddled the Amazon, and run around Mont Blanc,” he said. “And along the way we’ve been hit by lightning, mauled by a grizzly, and wrestled a boa constrictor.

"And all of these have been the experiences of fellow Minnesotans, most of them our immediate friends and neighbors.”

Pagel has climbed rock and ice on multiple continents, including summiting the Eiger north face, an infamous route in Switzerland that’s killed dozens of climbers. He wrote for national climbing magazines, often humorously about the frustrations of being a serious climber in the topographically challenged Midwest. His work is compiled in "Cold Feet: Stories of a Middling Climber,"a book illustrated by Duluth artist and climbing partner Rick Kollath.

The Duluth Explorers Club is usually held the third Thursday of the month. Attendance is free, but a climbing helmet gets passed around for donations that go toward funding youth climbing programs.

If you go

- What: Duluth Explorers Club featuring Duluthian Randolph Beebee, who will discuss his 4,000-mile trip in a Piper Cub floatplane across the far Canadian north, tracing the routes of famous Arctic explorers like Sir John Franklin, whose entire expedition perished on the Arctic Ocean.

- When: 7 p.m. Feb. 20

- Where: Spirit Mountain Grand Avenue Chalet, Duluth

- More info: duluthclimbers.org/duluth-explorers-club