DULUTH — For eight hours a day during the winter, Carson Spohn stone grinds, edges and waxes dozens of skis at the Ski Hut, where he’s worked since 2007.

“It’s my deal,” he said. “I love it. I get to sit back here, relax and scrape skis all day.”

ADVERTISEMENT

Just a few years ago, in preparation for cross-country races like the American Birkebeiner, he’d regularly melt on fluorinated wax for customers that sold for $100 a gram.

Fluorinated, or fluoro, wax boasts superior water and dirt repellency, leading to blazing-fast skis on warm winter days. This better skiing through chemistry was made possible by PFAS chemicals, which in recent years have been found to be harmful to people and the environment, prompting widespread bans.

PFAS, an abbreviation for "perfluoroalkyl and polyfluoroalkyl substances," are called "forever chemicals" because they linger for centuries. While waxing, skiers take chemicals into their bodies through inhalation, ingestion and skin absorption.

Until recently, fluoro waxes were widely used in all forms of skiing and snowboarding. In the first study to measure PFAS levels specifically in skiers, the Boston University School of Public Health released results in November that it found PFAS chemicals in 100% of the skiers and snowboarders tested, with higher levels in cross-country skiers.

According to the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency, PFAS chemicals “cause reproductive and developmental effects, impair liver and kidney functions, disrupt thyroid hormones, impact the immune system in laboratory animals, and cause cancer tumors in animals.”

The Boston University study found skiers with higher PFAS levels also had correspondingly higher levels of cholesterol, a surprise given the superior fitness level of the skiers tested.

“As Nordic skiers we’ve always known it’s not good, but we justified it by, ‘Oh, we’re only using a small amount and it’s very expensive and we only use it for important races,'" said Dave Johnson, Nordic ski coach at Marshall School in Duluth.

ADVERTISEMENT

When health warnings about fluoro waxes began circulating several years ago, Johnson purged the Marshall team’s waxing shed and brought all the fluorinated waxes to Duluth's Western Lake Superior Sanitary District Household Hazardous Waste facility, which will properly dispose of such waxes.

PFAS exposure is not limited to those who apply the wax; it flakes off skis and snowboards and enters the environment.

“Think about Spirit Mountain and all those skis,” said Jake Boyce, wax guru at Ski Hut. "All that snowmelt draining into Knowlton Creek and then the river and Lake Superior.”

A study done in Norway found voles living near a ski trail had PFAS levels six times higher than voles that live deeper in the forest. Those levels are not considered toxic, but due to the persistent nature of the chemicals, predators of the voles could accumulate much higher levels.

“Cross-country skiing is such a silent sport that’s built around the environment,” said Spohn, “but then everyone’s putting poison on the bottom of their skis and goes out in the woods, and nobody talks about it.”

Fluoro waxes are now banned from virtually all levels of competition.

The Boston University study found PFAS levels were highest in ski coaches, veteran athletes and those who waxed more than 100 pairs of skis in a year. A 2010 study on professional waxers found PFAS concentrations in the blood of cross-country wax technicians were as high as workers in a factory that manufactured PFAS chemicals, at levels 45-50 times above average.

ADVERTISEMENT

These days, when Spohn is asked to put on fluoro wax, he’ll wear a respirator.

“There are a couple people, and their kids ski race, and they want to cheat, and they’re like, ‘Put the good stuff on,’ wink, wink,” he said.

Ski Hut no longer sells fluorinated wax, nor does Continental Ski & Bike in Duluth, which sold its last in 2021. Spohn hasn’t applied any this season. Despite a national ban by the EPA, fluoro waxes are still available for purchase online.

The Minnesota High School Nordic Ski Coaches Association began banning fluoro waxes from regular season use during the 2016-17 season, though the wax was allowed in postseason races for several years. At the planet’s elite level of skiing, the International Ski and Snowboard Federation, or FIS, instituted a complete ban on fluoros for the 2021-22 season. The Birkebeiner ski marathon in Hayward, Wisconsin, followed suit.

“We test some skis,” race director Ben Popp said. “We hope the fear of maybe getting tested stops most.”

Fluoro bans are mostly on the honor system. Testing devices that provide immediate results are prohibitively expensive, costing around $25,000, and only used by the highest level of competition. Last March, when Minneapolis hosted the world’s best skiers during a World Cup race at Wirth Park, Duluth resident Gary Larson ran the PFAS testing machine for the FIS.

Larson is one of a handful of Minnesotan International Technical Delegates with the FIS. “It’s a pretty slick thing,” he said of the tester, which is a spectrometer connected to a laptop.

ADVERTISEMENT

A former ski coach at the University of Minnesota Duluth and the U.S. national team, Larson said violations of the fluoro wax ban among FIS skiers are rare. The only instance he is aware of happened last year in a downhill ski race and resulted from tainted waxing equipment rather than ill intent.

“The new waxes are not quite as fast,” Boyce said, “but they’re pretty dang good. The trade-offs for saving our bodies and the environment are well worth it.”

“I’m glad the fluros are gone,” Spohn said as he stood at his wax bench. “But these companies will just find something to replace it. You don’t know what’s in any of these. The stuff is crazy.”

He points to health warnings on the back of a bottle of new, nonfluorinated spray wax that has an icon of a fish floating belly up in water, followed by the word "vaara," which means "danger" in Finnish. As an avid fly fisherman, Spohn said the dead fish image bothers him.

“What’s in them? I couldn’t tell you,” Larson said of the new waxes. “I would hope that anything being used is somehow tested ahead of time.” However, he’s not aware of any such testing.

“You just hope that whatever’s used doesn’t have the same effect as the PFAS," he said. "Who knows? We didn’t know that fluorocarbons were going to be bad.”

Mike Hecker lives in the Twin Cities and runs, with his two sons, a small distribution company that supplies wax to the Ski Hut.

ADVERTISEMENT

Hecker is well-known in the ski community for managing the Nordic high school state meet. His son, Chris, is the head glide wax technician to the U.S. Nordic team and is currently in Norway waxing skis for the national team, including Jessie Diggins, as she competes for another World Cup title.

When Chris Hecker waxes for the U.S. team, he wears gloves and a respirator. The Heckers sell Rex Wax, made, like most ski wax, in Europe. Hecker credits the European Union’s stricter environmental regulations with prompting the worldwide move away from fluoro wax.

Still, “I don’t have a clue,” he said, as to what the replacement chemicals are in the new waxes. Hecker trusts EU rules in making sure they’re safe.

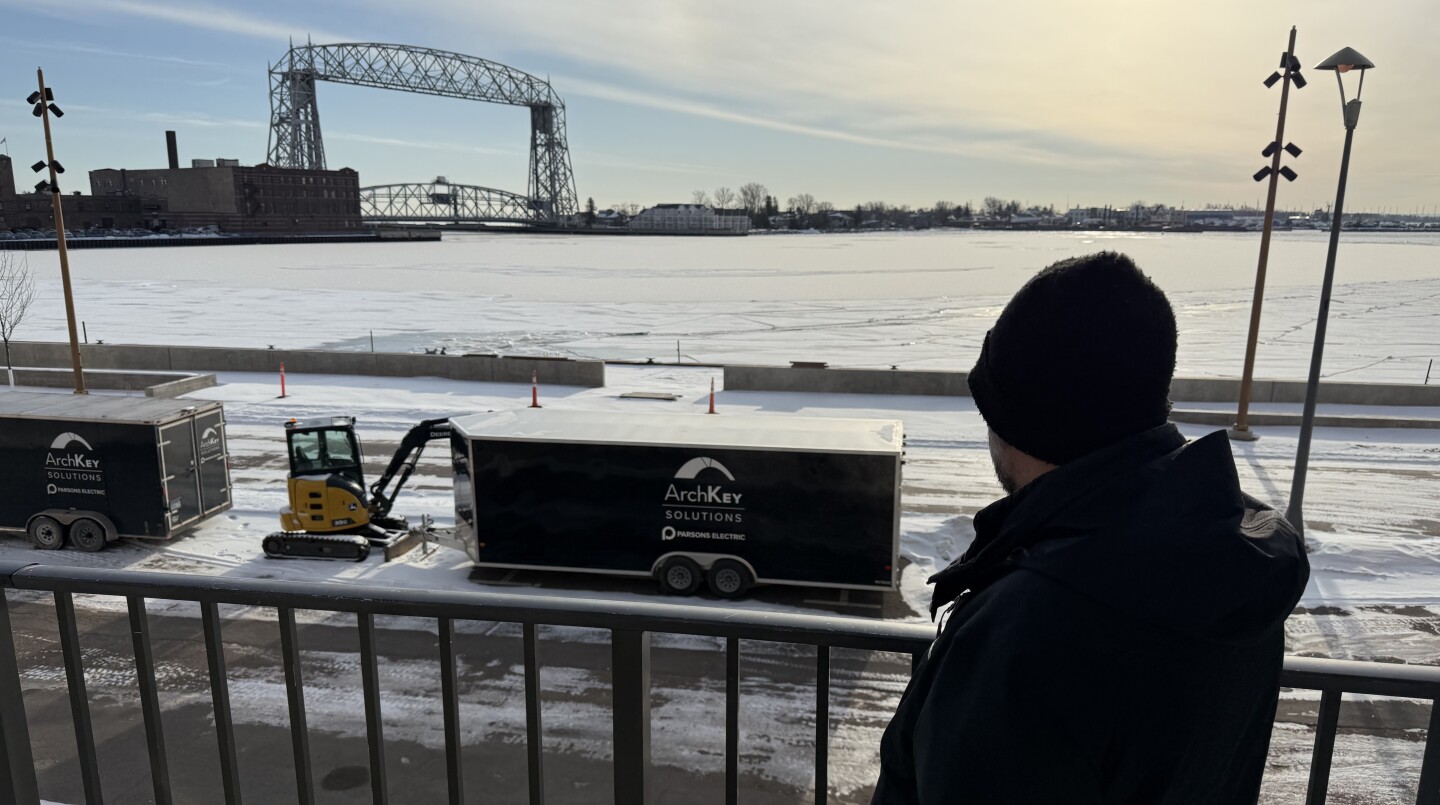

Student-athletes with Marshall and Duluth East high school ski teams no longer wax their skis. At Marshall, Johnson and the other coaches put on respirators and go into a well-ventilated trailer where they spray on nonfluorinated wax.

“We form an assembly line — one person applying, one person brushing. We can get through 20 or 30 skis in an hour,” Johnson said. “We’re finding our skis are fast, maybe not the absolutely fastest, but they’re competitive.”

East High School coach Bonnie Fuller-Kask said they've been "hearing about the dangers of fluoro wax for a long, long time."

"As a high school team, 10 or 12 years ago, we started waxing in a trailer outside with vents," she said.

ADVERTISEMENT

At East, too, coaches do all the waxing, both for the kids’ safety and also “because kids are notorious for using way more than they really need," Fuller-Kask said.

She hoped the new, nonfluorinated waxes would cost less, but they’ve proven to be just as expensive. A film canister-sized container can cost $100. East spends $2,000-$3,000 a season on wax.

Fluorinated or not, Fuller-Kask said the East team will continue to treat the new waxes as potentially toxic. “I don’t know what’s in them," she said. "I hope they’re safer. Our waxers will keep using masks.

“I think people should be really careful when we put these new waxes on because we just don’t know," she said.