You may not be familiar with the Quadrantids (KWAH-dran-tids) meteor shower, but it's an annual event just like the Perseid meteors of August. Every year in early January, the Earth zips through a trail of dust and rocky fragments released a few hundred years ago by the object 2003 EH1.

Most meteor showers have a "parent" comet. Comets are composed of dust and rocks bound up in ice. When a comet passes near the sun, solar heating vaporizes some of the ice, releasing the dust. That debris not only makes a tail, but also spreads around the comet's orbit to form a stream of rocky particles. When Earth passes through the stream, the fragments strike the atmosphere, heat up and streak across the sky as a shower of meteors. "Shower" implies a steady "rain," but for most of us these events might be better described as meteor "sprinkles."

ADVERTISEMENT

2003 EH1, the Quadrantid shower's parent, is classified as an asteroid, but its tilted orbit is more like that of a comet. Even though it's never looked fuzzy or sprouted a tail, many astronomers consider it a dormant or "occasional" comet rather than a rocky asteroid. Either way, it ejected a bunch of material sometime between the years 1700 and 1800. This now forms the dense core of the annual meteor shower.

Most meteor showers show strong activity over 2-3 nights. The "Quads" are unusual in having a brief but intense peak lasting only a handful of hours. This time around that occurs on Friday morning, Jan. 3 at about 9 a.m. CST — not exactly an ideal time for meteor-watching. But if you live farther west, say in Alaska, where it's still dark at that hour, it will be one of the best showers of the year. From a dark sky before dawn, you might see as many as 100-plus meteors per hour.

Those of us not so ideally situated will spy closer to 25 per hour Friday morning between 2 a.m. local time and dawn. Especially bright meteors called fireballs are common among the Quadrantids, so expect a few fireworks.

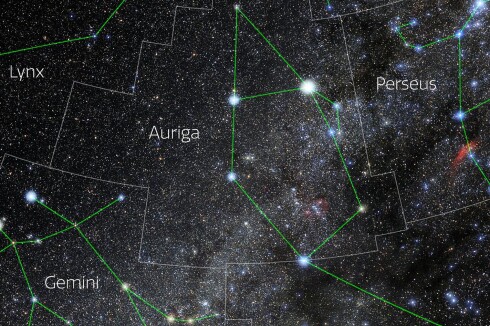

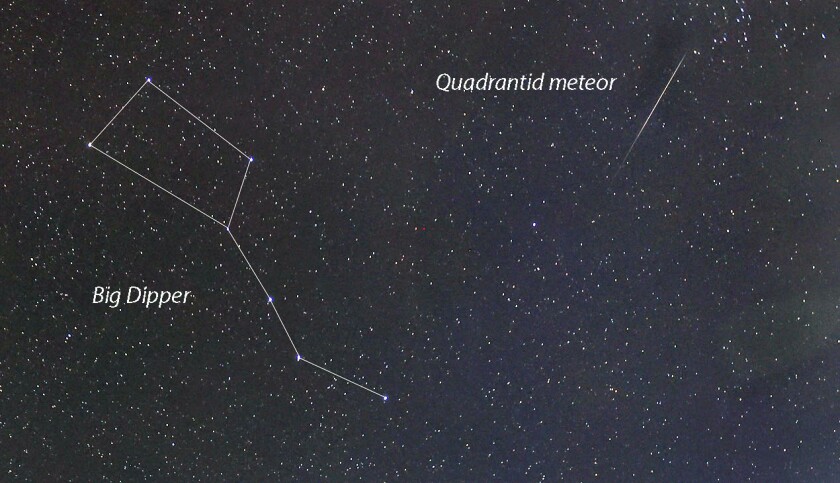

The shower gets its name from the obsolete constellation Quadrans Muralis the Mural Quadrant, a pattern of faint stars about 15 degrees below the handle of the Big Dipper. Long ago, astronomers used mural quadrants to measure the altitudes of celestial objects. Although both the constellation and instrument fell into disuse, the name is forever preserved in January's premier meteor event.

The streaming location, called the radiant, stands highest in the northeastern sky in the early morning hours. Each meteor you'll see was once a piece of 2003 EH1. Striking the atmosphere at around 92,000 mph, the particles compress the air along their path, which not only heats them up, but also excites oxygen and other atoms to glow.

Few people observe the Quadrantid shower because it occurs during the coldest time of night at the coldest time of year. Still, if you're able, I'd encourage you to go out and watch this well-kept secret. Meteors will appear in all parts of the sky, but your best direction is the one facing the least amount of light pollution. A wide-open spot with a lot of sky is a plus.

Dress warmly, relax in a lounge chair under a warm blanket and settle into the moment. I usually spend 1-2 hours watching. The regional forecast is for partly cloudy skies Friday morning, but if it turns out to be cloudy, you'll still see a few meteors the following morning. Happy gazing!

ADVERTISEMENT