DULUTH — For two nights in 1953, Duluth News-Tribune reporter Walter Eldot and a staff photographer donned old clothes and walked into the Bethel Building at 23 Mesaba Ave.

No one at the facility, which provided board and lodging to indigent or elderly men, questioned the pair or asked them to sign in. So for two nights, they wandered the building posing as transient men, spoke with those staying there and took candid photos of its conditions.

ADVERTISEMENT

The result? A two-page spread in the Sunday, May 31, Cosmopolitan magazine insert of the News-Tribune titled “Some Men Prefer to Sleep on the Floor,” a quote by Bethel’s superintendent, William Grobe.

It included Eldot’s observations and several photos by the unnamed photographer showing men sleeping on the floor, a bench and a crowded bunk room.

“I saw a night clerk walk past a bathroom where two men were sleeping on the wet floor. He made no attempt to wake them. I saw men flop down where they fell,” Eldot wrote. “No one cared.”

But they didn’t need to sleep on the floor. Beds were available.

“Petty thefts are common at the Bethel, and that is one of the reasons why men sleep in their clothes,” Eldot wrote. “On both nights I observed a score of empty bunks in which someone could have slept.”

The article is a deeply reported investigation into living conditions at Bethel. It detailed five men who contracted tuberculosis at Bethel in the first five months of that year, and two of them died. The building was “infested” with bedbugs and cockroaches, yet men slept in their street clothes and blankets were used for months without a wash. There were showers and a bathtub, but towels and soap were not provided. "Men with contagious ailments, open sores and rashes have been found on kitchen duty.”

Eldot is quoted in a preview of the article saying he spent a week in the Bowery — a seedy area that included the 400 and 500 blocks of West Superior Street — exploring the “flop houses, bars, hallelujah mission, hash joints, street corners and hangouts where down-and-outers in our city while away their days.”

ADVERTISEMENT

“Whoever I talked to, wherever I went, the road led back to the Bethel — regarded as a haven of refuge by many, a despised dungeon of indifference by some,” Eldot said.

Supporting his observations with documentation from civic and health officials, Eldot’s article spurred much-needed reform, repairs and improvements at Bethel.

Within days, men were taken to Nopeming Sanatorium for TB examinations, sleeping was prohibited on floors and hallways if beds were available and three truckloads of years-old and “spoiled” canned goods were taken to the city dump, Eldot reported in the June 4, 1953, Duluth Herald, the evening paper.

Meals improved, too, with the addition of butter and bacon, he wrote.

Over a year later, the News-Tribune revisited Bethel for an article in the Sep. 26, 1954, News-Tribune with the headline, “No Palace — But It’s Much Better.”

Those changes included fresh paint and a sanitary kitchen with new equipment and meals. Everyone also received soap, towels, bed sheets and pillowcases. Eldot wrote that there were fewer bedbugs and lice.

“Life on the Bowery doesn’t change much in a year. The bars, hock shops, the old fire-trip flop houses — they’re all the same. And the shabby men who live in those environs also still go about their habitual ways,” Eldot wrote. “But up at the Bethel on Mesaba avenue and First street, the changes of the past year are impressive. They are bright spots in a dismal pattern and reflect credit on those who, in Jesus’ name, say: ‘Come!’”

ADVERTISEMENT

Today, Duluth Bethel is in its 151st year of serving the area. It’s secular now, with a focus on substance abuse and corrections. It still operates out of the same facility on Mesaba Avenue and West First Street that Eldot would have visited.

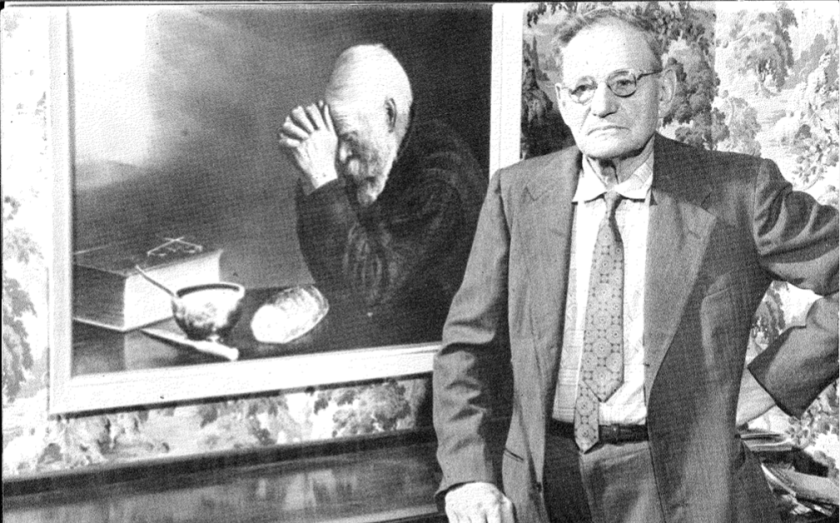

After the article came out, Bethel invited Eldot to serve on their board, which he did until his death on June 30, 1987.

According to the biography attached to his collections at the University of Minnesota Duluth Archives and Special Collections, Eldot experienced poverty in childhood, which shaped his volunteer and community work.

Born in Germany to Jewish parents in 1920, he and his brother fled to the U.S. in 1936, but his father died at Buchenwald, a Nazi concentration camp, the biography said.

In a news obituary that ran in the Minneapolis Star and Tribune on July 8. 1987, Eldot’s wife, Goldie, said he was driven to advocate for the less fortunate, including when he served on a parole board for young offenders in the state.

“He was always so interested and concerned about the underdog and the poor,” Goldie said.