CLAYTON, Calif. — When Dianne Carbine was a little girl, she often asked her mother, Dorothy, about her father, Herman.

Who was he? What was he like?

ADVERTISEMENT

But Dorothy rarely answered.

“She was just so despondent over losing him that it was too hard for her to talk about it and share a lot,” Carbine said. “She always said that my dad was the love of her life.”

Carbine craved that knowledge because she never met her dad. He was killed in WWII six weeks before she was born.

Dorothy was not only pregnant with Diane, but she was also caring for her young son, Denny. To make things even harder, she wasn’t given the chance to properly grieve her husband.

All the family was told was that Herman Sundstad was killed in Burma on June 5, 1944. However, his remains were not identified or returned to the family.

“We never knew anything about him. We never knew exactly where he died, how he died, where his body was and his circumstances. He was gone, and he wasn't even declared dead. He was considered unrecoverable. We had no closure. Is he lying someplace in Burma? Is he there? We had no idea,” Carbine said.

Dorothy went on to remarry, build a life and raise a family while seemingly locking her true love deep inside her heart.

ADVERTISEMENT

Now, 80 years after his death, Herman Sundstad’s family will finally lay him to rest as they grieve his loss and honor his memory thanks to the Army’s persistence, scientists' dedication and DNA, all of which are providing closure to a family who has had so little of it.

'The professor'

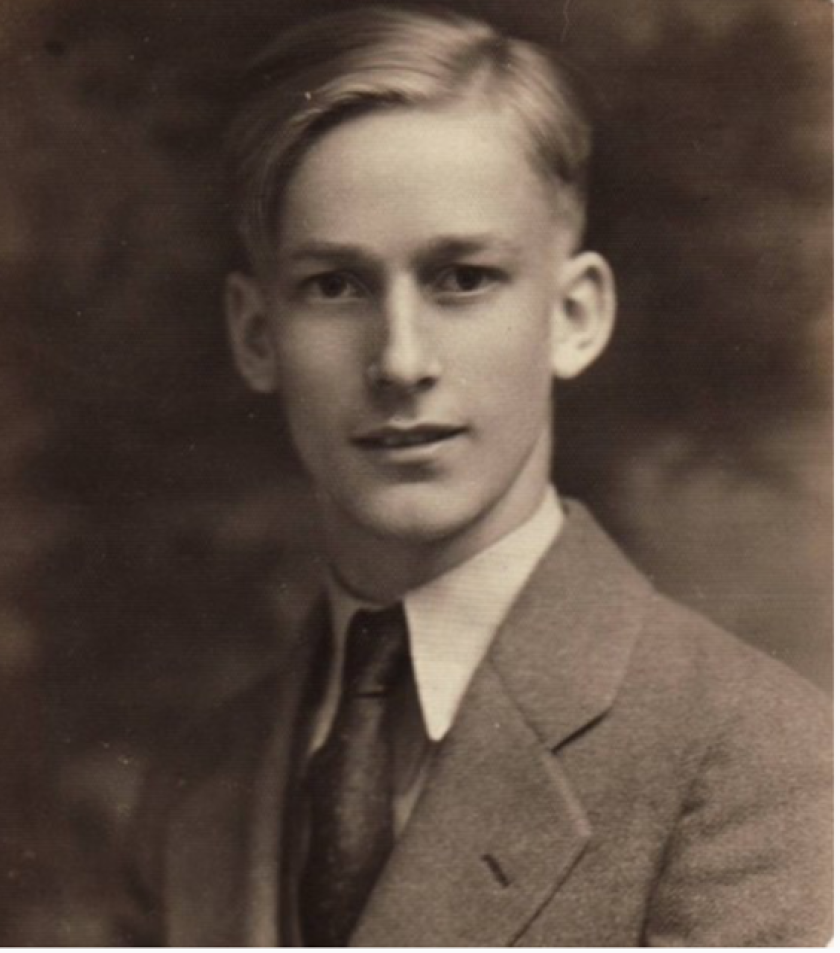

Herman was the sixth of nine children born to Norwegian immigrant parents on a potato farm near Perley in Norman County, Minnesota. While his older brothers left school after eighth grade, he was the first Sundstad boy to graduate from high school. He was even nicknamed “the professor” by some.

“He was very studious, ambitious and kind,” said Mary Sundstad, whose father, Elmer, was Herman’s older brother.

Herman then attended Moorhead State Teacher’s College, now Minnesota State University Moorhead. After earning his degree, he taught school in Minnesota before going to the University of Minnesota to pursue a master’s degree.

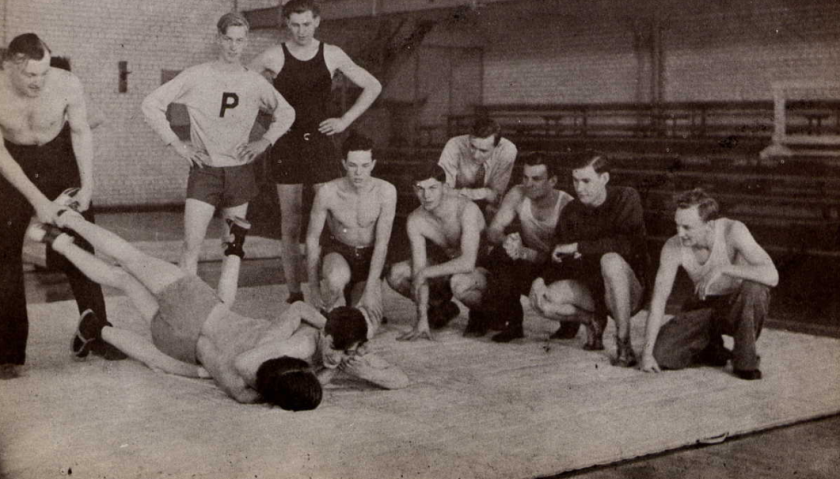

While there, he joined the U.S. Army and served with the 5307th Composite Unit (Provisional), a volunteer-only Special Operations Light Infantry Unit known as Merrill’s Marauders.

Merrill's Marauders — the forerunner to the U.S. Army Rangers — was an elite American military unit that fought in the China-Burma-India Theater of World War II. Named after and led by Brig. Gen. Frank Merrill, the group became legendary for its grueling jungle warfare against Japanese forces in Burma, which is now Myanmar. Malaria, dysentery and other tropical diseases were as deadly as the combat itself.

The unit relied on volunteer soldiers, like Herman Sundstad, while hoping to retake Burma from Japanese occupation.

ADVERTISEMENT

The survival rate was low. Sundstad didn’t need to enlist.

“But he was a leader, I think that was in his nature. He wanted to serve,” Mary Sundstad said.

In May of 1944, the Marauders seized a strategic airfield near the village of Myitkyina, which started a major battle to drive out Japanese forces from the area. It’s believed Sundstad was killed while on patrol behind enemy lines.

Of the 2,600 Merrill’s Marauders who crossed into Burma in 1944, just 130 able-bodied soldiers remained three months later.

Sad news comes to Norman County

Mary Sundstad said her father never forgot that day in 1944 when the family learned Herman had been killed.

Elmer, who was two years older than Herman, wasn't in the Army because he was given a deferment to run the family farm following the death of their father, Einer, in 1941.

In addition to Herman, three other Sundstad sons were off at war.

ADVERTISEMENT

“My dad was in the field and saw a jeep driving up to the farmhouse," Mary Sundstad said. "He knew right away that one of his brothers was either dead or injured, so he stopped the tractor and ran to the farmhouse."

He wanted to get to his mother before the men in the Jeep could. Mary gets emotional imagining how heartbroken the family must have been when those men gave Clara Sundstad the heartbreaking news about Herman.

“I remember when I was young, we could never mention my uncle around my dad because he would get too upset, you know, kind of a Norwegian thing, not to voice how much you miss someone,” she said.

DNA Samples

Fast forward decades. Herman Sundstad’s parents and wife died, and Carbine continued to think about her dad.

“I never got to know him, but I have felt him through my life, especially when I've had my children,” she said. “I don't know if it’s my imagination, but I felt like he's been with me a lot during my life.”

Thanks to advances in DNA technology, the Army had greater hope to reunite the remains of unidentified WWII soldiers, like Sundstad, with their loved ones back home.

In 2018, the Defense POW/MIA Accounting Agency began exhuming remains associated with the Battle of Myitkyina, which had been buried at the National Memorial Cemetery of the Pacific in Honolulu for the last 80 years. Could these remains belong to Sundstad?

ADVERTISEMENT

The agency contacted Carbine and some of her cousins, who had once lived in Gardner, North Dakota, to obtain DNA samples.

Carbine said she didn’t think much would come of it; her son, Ben Porter, stayed in communication with the Army, hoping for answers and doing more research about his grandfather.

“I’ve always had a weird connection with him (Herman). I can’t explain it. For some reason, I felt like I had some inner connection to him,” Porter said.

He even gave his youngest son the middle name of Herman.

Then word came on June 24 of this year, just over 80 years since Herman Sundstad died in Burma. Thanks to the DNA samples from Carbine and the cousins, Herman’s remains were positively identified. He would be coming home to the daughter he never met.

The funeral

Carbine said she’s been totally overwhelmed by the range of emotions she felt since getting the news.

ADVERTISEMENT

“It’s all a whirlwind,” she said.

The family started planning to bury Herman in the same cemetery in Lafayette, California, where Carbine and her husband have plots. Herman and Dorothy settled in the area after meeting while he was stationed at Camp Roberts near San Miguel.

When Porter called on behalf of his mom, he was told there were no plots near the family plot.

“A week later, the cemetery guy called me and said, ‘You won't believe this! Those two plots right next to your parents? Well, the owners just called wanting to sell them back to us because they don't want them anymore,’” Porter said.

Herman could be buried right next to his daughter.

Carbine called it “a tender mercy” and “a minor miracle.”

This Veterans Day, Herman Sundstad, 80 years unaccounted for, will receive a hero's welcome home to California with all the military honors, pomp and circumstance befitting a Purple Heart and Bronze Star recipient. The Army recently gave Carbine those awards along with eight others.

Several family members are flying in for the funeral, including Herman’s namesake great-grandson, 7-year-old Benjamin Herman Porter.

“I wish he were a little bit older, but I'm going to talk with him on the plane and tell him this is something you need to put in your long-term memory,” Porter said.

He said his older children are not too pleased that their little brother is the one who gets to take the trip from Massachusetts to California, but fifth grader Max has good reason to stay home.

“They had to do a Veterans Day essay, and the winner gets to read it to the whole assembly. So on Friday, the same day we receive the body, he’ll be reading that essay about his great-grandfather,” Porter said.

He said this has been an emotional chapter in his family’s life, especially for his mom.

“I think she feels like she’s grieving for the first time, even though he’s been gone for 80 years. It’s very visceral, very emotional for her. She and all of us are very appreciative of the military and all of the scientists for everything they’ve gone through to identify him,” Porter said.

The only thing missing this Veterans Day is Dorothy, the wife who grieved her "true love."

“I wish she were here to see this. But the fact that my mom is getting to see this is a huge blessing,” Porter said.

“I've been waiting 80 years for them to bring my dad home, and now they're going to,” Carbine said. "They’re honoring my father after all of these years. I still can’t believe how powerful this has been.”