Editor's note: This story is part five of an eight-part series examining the killings of Gilbert Fassett and Eddie Peltier on the Spirit Lake Nation in North Dakota. Veteran reporter Patrick Springer examines both cases and considers a sobering question: Were the men convicted of these murders guilty?

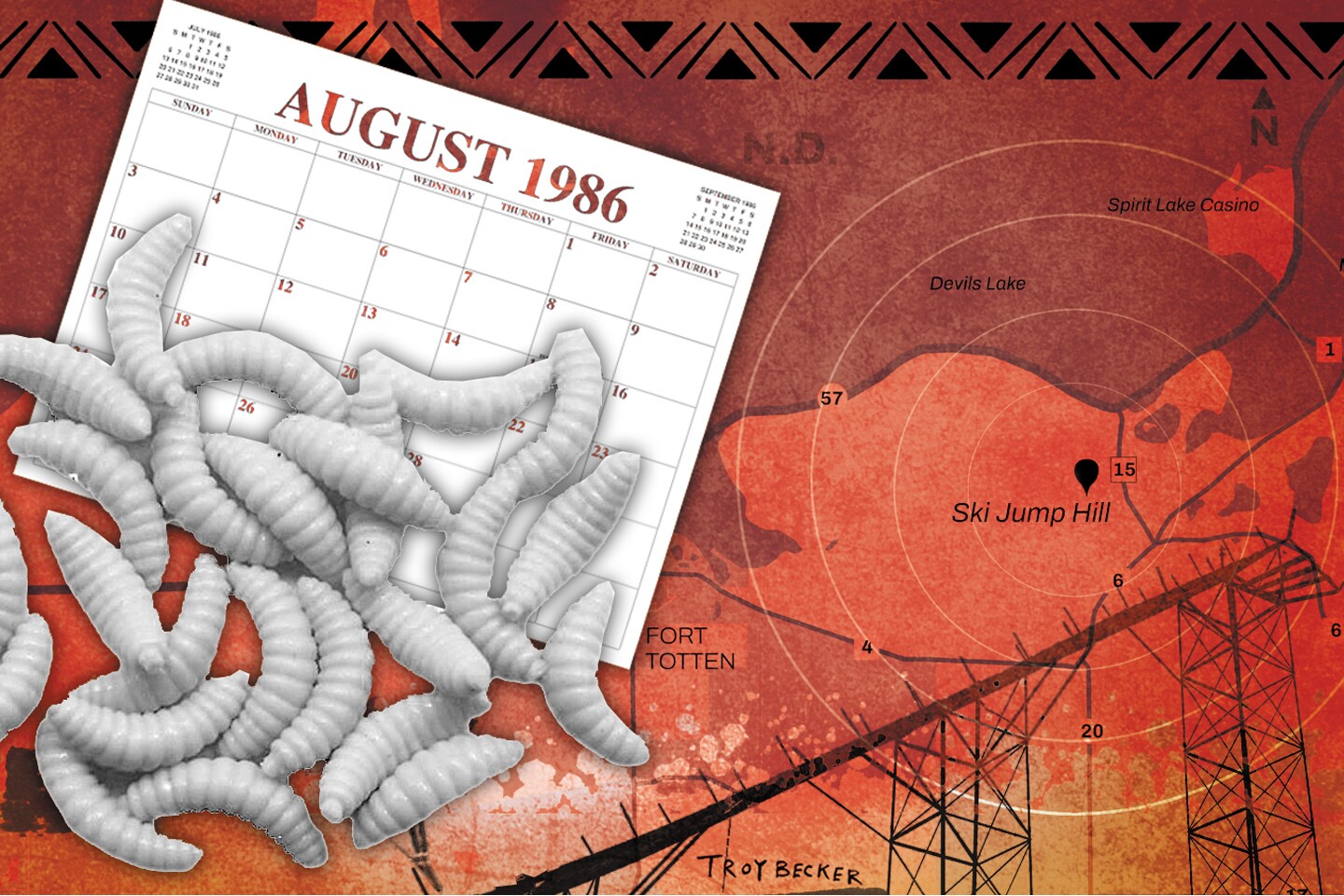

DEVILS LAKE, N.D. — Maggots scraped from the badly decomposed body of Gilbert Fassett were “silent witnesses” critical in establishing when he was murdered.

ADVERTISEMENT

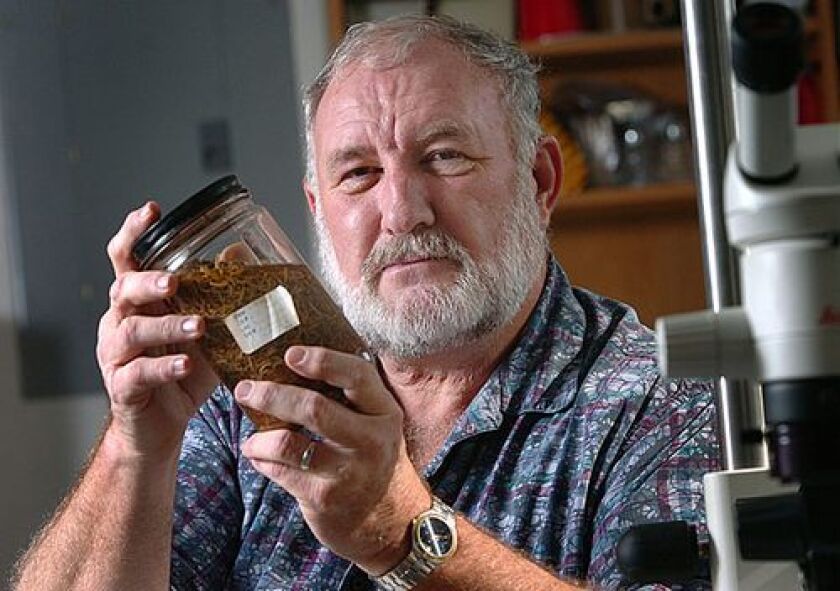

Omer Larson, a zoology professor and parasitologist at the University of North Dakota, was called upon by the prosecution to analyze the maggots in order to estimate Fassett's time of death.

Larson concluded that Fassett had been killed on Aug. 1, 1986 — the last day he had been seen alive.

That determination had dire consequences for Werner Kunkel, who was the last person known to have been with Fassett, an acquaintance he’d given a ride on that date.

Kunkel was convicted in 1995 of Fassett’s murder in a case that was mostly circumstantial and depended heavily on witnesses who claimed that Kunkel had confessed the murder to them.

Kunkel’s lawyer didn’t challenge the forensic entomological evidence — which he dismissed as “fuzzy science” — even though, left unchallenged, the established time of death greatly hindered the defense by leaving a brief, critical period for which Kunkel couldn’t provide alibi witnesses.

The reliability of Larson’s forensic entomological evidence was one of the main issues raised in a 2005 appeal seeking a new trial for Kunkel, who changed his last name to Rümmer after the trial.

The appeal noted that the Aug. 1 estimate for the date of Fassett’s death based on the development of the maggots found on his body conveniently matched the prosecution’s theory that Fassett was murdered shortly after he was last seen with Rümmer on that date.

ADVERTISEMENT

Failure to challenge the forensic entomological evidence and to challenge the credentials of the expert witness meant Rümmer was given ineffective counsel during his murder trial, argued the appeal filed by Douglas Broden.

“ … in this instance the determination of the time of death was extremely crucial as Mr. Rümmer has an alibi for all times other than the time that the State erroneously contends that death occurred,” Broden wrote in his brief. “Failing to fully investigate the accuracy of this expert testimony foreclosed the possibility of asserting an alibi defense.”

Rümmer’s trial lawyer, Todd Burianek, testified at the appeal hearing that he didn’t view Larson’s testimony as significant, coming from a “UND professor who had a hobby of looking at bugs, and I just didn’t believe that it would rise to the level of being that significant in light of all the other evidence of the case.”

Burianek said he didn’t want to “legitimize” Larson’s opinion by dwelling on his testimony. “Look,” he said, recalling his thinking at the trial, “this case isn’t going to be a conviction based on what a bug doctor says.”

Instead, he thought the trial outcome would hinge on the testimony of witnesses who claimed Rümmer confessed committing the murder to them.

For the appeal, Broden hired Neal Haskell as a defense expert to examine the maggots in order to determine the time of Fassett’s death.

Haskell is a board-certified entomologist with the Entomological Society of America and a diplomat of the American Board of Forensic Entomology who has testified as an expert in hundreds of criminal trials. As of 2005, he said he had provided forensic entomology analyses in 1,700 cases.

ADVERTISEMENT

By contrast, Larson, the prosecution’s witness, is not a forensic entomologist and should not have been accepted as an expert in the field, Broden argued. Larson testified that he had been called upon by law enforcement three times before the Fassett murder case, which was the first in which he testified to give his opinion.

Haskell came to a different determination of Fassett’s death. He concluded death occurred after sunrise on Aug. 3 to sunset on Aug. 6.

Fassett’s badly decomposed body was found on Aug. 10. The pathologist who performed the autopsy on Aug. 11 estimated Fassett had been dead for at least seven or eight days, based on the condition of the body.

In Haskell’s opinion, it was not possible that Fassett died before sunset on Aug. 2. Haskell, who said he had examined “hundreds of thousands of specimens,” said Larson failed to meet the standards of a board-certified forensic entomologist.

In calculating his estimate, Haskell used the life cycle of blowflies, which lay eggs on dead bodies. Depending upon temperature, blowfly eggs will hatch within a few hours if it's warm or a couple of days if it's cool.

The eggs then develop and once they reach the larval stage reach larval mass.

Haskell used hourly weather conditions for Devils Lake from the National Weather Service to compute the “energy units” available for the developing larvae.

ADVERTISEMENT

Larson used weather information from a local radio station provided in six-hour increments — not precise enough to come up with a reliable estimate of Fassett’s time of death, Haskett testified.

Also, Haskell said, Larson made computational errors that resulted in an inaccurate time scale of maggot development that in turn made his estimated time of death on Aug. 1 too early.

“I feel that there was an overestimation of the age of the larvae and an underestimation of the energy units available,” Haskell testified in the hearing. “I think if the two analyses were put on the same scale with the same factors, I think that certainly that time would have been shortened from the Aug. 1 date,” to a date ranging between after sunrise on Aug. 3 to before sunset on Aug. 6.

In his testimony, Larson acknowledged that he at first misidentified the insect species, mistaking blowfly larvae for screw worm larvae, an error he caught nine years after his examination, when the FBI asked him to review his findings before Kunkel’s 1995 trial.

Larson also said he did not ask the pathologist for live maggots so they could mature for positive identification.

The North Dakota Supreme Court rejected the appeal, including the argument that the trial lawyer’s failure to investigate the scientific evidence constituted ineffective counsel. Appeals courts are reluctant to second-guess a trial lawyer’s strategy, the justices wrote.

“From our review of the record, we conclude Rümmer’s trial counsel’s representation did not fall below an objective standard of reasonableness and Rümmer has simply not demonstrated the testimony of any of his proposed additional witnesses would have changed the result in his criminal trial,” Justice Mary Maring wrote. “Rümmer was not prejudiced by counsel’s alleged deficient performance and he has failed to establish ineffective assistance of counsel based upon a failure to investigate.”

ADVERTISEMENT

In an interview with The Forum, Haskell said the specificity of Larson’s estimate for the date of Fassett’s death, pinpointing a single day, isn’t scientifically reliable.

“You can’t just get one day and say that’s it,” he said. “You have to have a range. There has to be a lower limit and an upper limit,” to account for variability of conditions.

As a result, given the significance of the time of death in the case, Haskell said Rümmer was deprived of a fair trial. Also, the pathologist who performed the autopsy, Dr. Roel Gallo, had only performed about 120 autopsies and was still in training. There was no indication he had previous experience autopsying badly decomposed bodies, Haskell said.

“He should not have been convicted,” Haskell said, referring to Rümmer. “Definitely not have been convicted.”

Because Rümmer’s defense lawyer didn’t challenge the evidence establishing Fassett’s time of death, Rümmer was left without an alibi defense. His trial lawyer zeroed in on the timeline and argued that Rümmer didn’t have time to do all that prosecutors said he did to commit the murder, move the body, clean up and dispose of evidence.

Witnesses last saw Fassett when he and Kunkel left Fassett’s step-parents’ house at around 10:30 p.m. on Aug. 1. Kunkel told investigators that he dropped off Fassett at a home where he was staying with friends between 11 p.m. and midnight.

He drove around Devils Lake, picking up a girl at around midnight, which the girl corroborated in her trial testimony. She said Kunkel appeared calm and she saw no scratches, scrapes or blood on him.

ADVERTISEMENT

A Highway Patrol officer stopped Kunkel south of Devils Lake at 1:13 a.m. Aug. 2 and gave him a warning. The trooper testified that he saw no blood on Kunkel or his car — which prosecutors argued Kunkel used to transport Fassett’s body — and also observed no scratches or scrapes on Kunkel.

That means Kunkel would have had between 1 1/2 and less than 2 1/2 hours to murder Fassett, drive the body about 10 miles from Devils Lake, about a 15-minute drive, where prosecutors said the murder occurred, to Ski Jump Hill on the reservation, where the body was found.

During those roughly 90 to 165 minutes, Kunkel would have had to load and unload the body, then drag it 25 feet down the hill in the dark, then wash blood off himself and his car as well as dispose of his bloody clothes and the knife used to kill Fassett, which never was recovered, his lawyer argued.