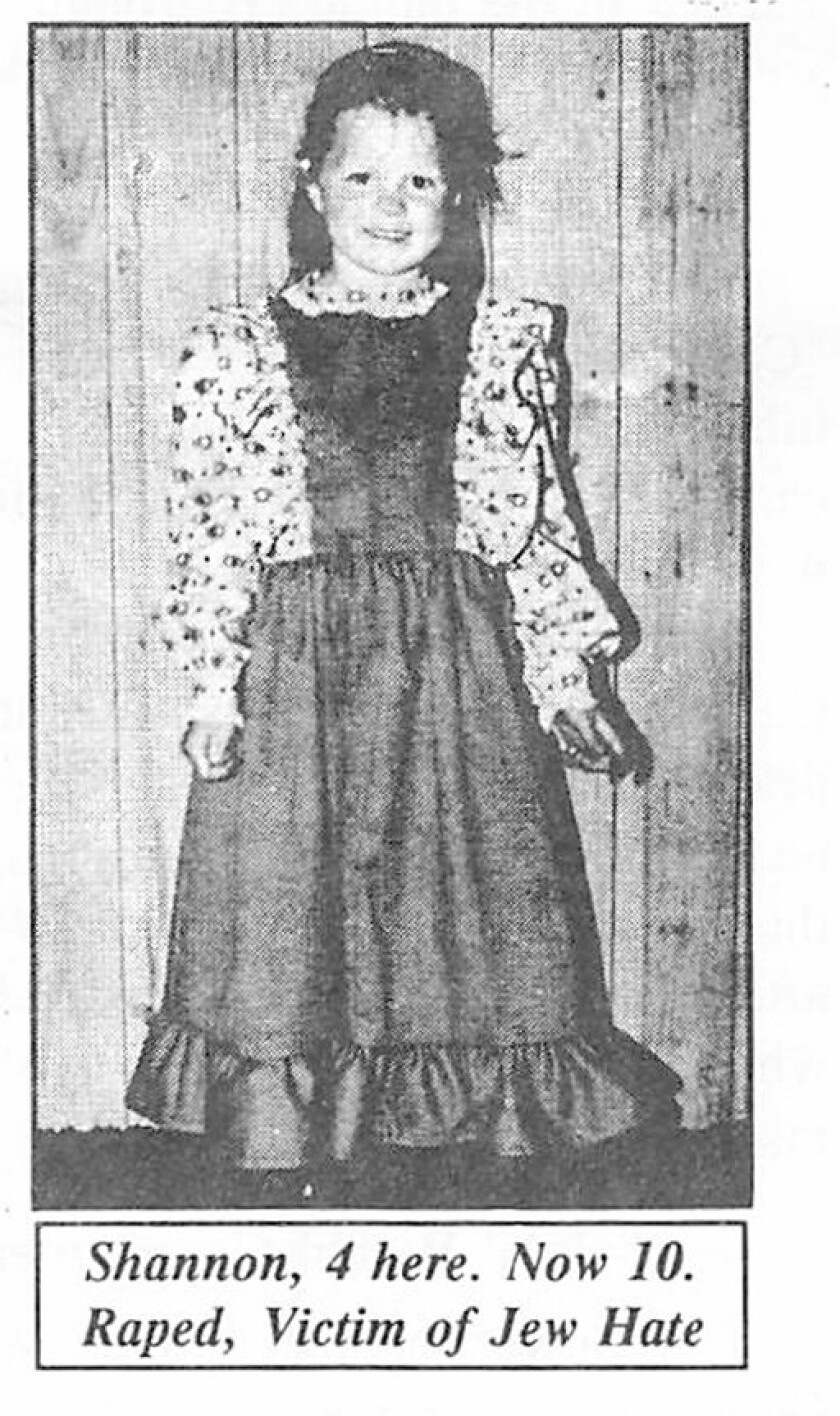

EDGELEY, N.D. — By the summer of 1996, Shannon Ness was lonely. Used to being surrounded by five brothers and sisters, one by one her siblings disappeared, kidnapped by family off their rural LaMoure County farm.

They were taken in the midst of a cult war, a family feud between the Lepperts of North Dakota and the Winrods of Missouri.

ADVERTISEMENT

At 7 years old, Ness — who grew up Shannon Leppert — knew where her brothers and sisters were taken. Followers of the Gordon Winrod cult secreted them into the Ozark Mountains near Gainesville, Missouri, a place she once visited, a place where Winrod, a Jew-hating, defrocked Lutheran preacher, hid her siblings and cousins at times inside a bunker called the “priest hole” until 2000, when authorities raided the 400-acre farm.

Before the raid, however, local authorities and federal agents were reluctant to investigate, Ness told Forum News Service, because they were shadowed by disasters like the 51-day Waco siege in 1993; the 1997 Heaven’s Gate mass suicide with the arrival of the Hale-Bopp comet, even the 1983 shootout between U.S. Marshals and tax protester Gordon Kahl in Medina, North Dakota.

“There were all these cults going on, and there were these massive messes that the government was involved in, essentially. So I do think there was really a reluctance to have law enforcement go in and get us, because they thought it would end up in a similar situation,” said Ness, adding that Missouri law enforcement “miserably” failed the Leppert children.

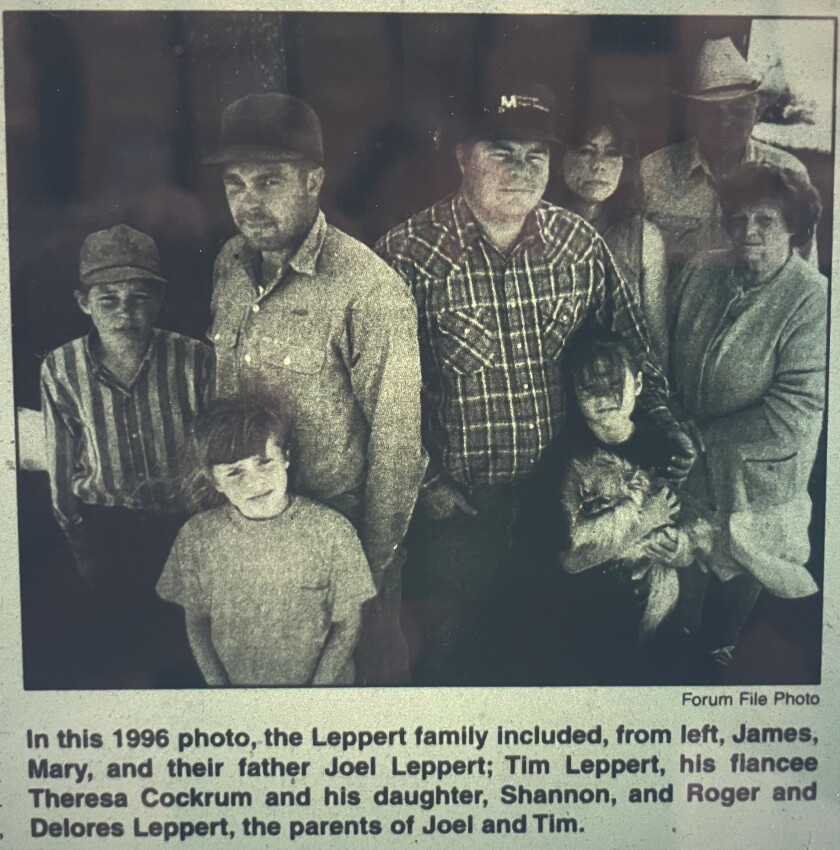

The story of the Leppert family began in 1978 when Roger and Delores Leppert, of Dickey, North Dakota, traveled to Gainesville, Missouri, with Kahl to meet Winrod, who at the time was leader of Our Savior’s Church.

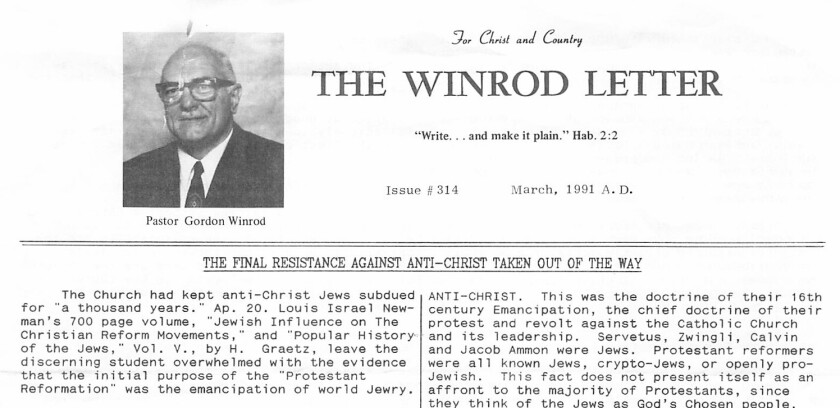

Moving away from mainstream religion, the Lepperts, Kahl and the Winrods were united by a message of hate, Ness said, which Winrod broadcasted over the radio on Mexican airwaves and published in the "Winrod Letters," multi-page documents written by Winrod and mailed to people across North Dakota in the 1990s and early 2000s. His message wasn’t new: anyone who didn’t subscribe to his philosophy were labeled Jews and part of a Zionist conspiracy to subjugate the world.

Urged by Roger’s sister, Inez Leppert, three of Winrod’s daughters married three Leppert brothers, Ness said. Two of the families had a total of 11 children.

But like many religious movements, money was at the cult’s core, Ness said. Around 1991, Winrod demanded that the Lepperts donate their farms to him and Our Savior’s Church, Ness said.

ADVERTISEMENT

At least two brothers — Tim and Joel Leppert — refused, and divorced their Winrod wives. The third, Sam Leppert, is still married to Laura, and ran for state representative in 2022 and lost .

Soon after the divorces, Winrod flooded North Dakota with his Winrod Letters through the mail, spreading what Ness called lies and he began organizing the abductions of the Leppert children.

Ness said the family feud forced her to grow up under the near-constant threat of danger while living with her father and his girlfriend, Theresa Cockrum. Ness couldn’t have friends. Cows were poisoned. Her family’s fields were sabotaged with junk to destroy tractors. Hay was once stacked at the corner of the house in what appeared to be kindling for a fire.

The LaMoure County Sheriff’s Office responded 130 times to the Leppert farm in less than two years, according to the Bismarck Tribune.

Followers of the Winrod cult succeeded in kidnapping eight of the Leppert children. But they wanted them all.

Ness vividly recalls the fourth — and final — time they attempted to abduct her.

ADVERTISEMENT

Shannon’s final abduction

Shortly before 2 p.m. on Aug. 21, 1996, Ness and her father’s girlfriend, Cockrum, had just finished brushing Twigs, a yearling filly. Country music filtered through the barn from an AM/FM radio, and they were “just having a good time, spending time with each other and hanging out with the horses,” Ness said.

Out of the corner of her eye she saw two mares inexplicably running around. “‘What’s going on?’” Ness remembered thinking.

Suddenly, the dimly-lit barn filled with sunlight. Two silhouettes entered.

“I saw the large spray cans in each of their hands, spraying a green substance at me,” wrote Cockrum, in her testimony to Stutsman County District Court.

Ness remembered Theresa pushing her toward a tack room, to a hole in the wall where she could escape.

Cockrum’s eyes adjusted to the brightness as she moved back, still gripping Twigs’ halter. The first mace spray missed her, but the barn was filling quickly with the nauseatingly cloying scent of apple blossoms.

One of the silhouettes rounded Twigs. It was Sharon Leppert, Ness’s mother.

ADVERTISEMENT

Cockrum’s eyes began to sting. Her throat tightened. She fell into a pile of straw, she wrote.

Sharon wasted no time. She ripped the halter from Cockrum’s hands and began spraying mace directly into her face for about half a minute, Cockrum said.

“I had my hands clamped over my face and my eyes shut to try to keep the mace out of my lungs and eyes. I could hear the horse stomping around. I didn’t know where Shannon was or who the other person was,” Cockrum said.

“When she finished spraying me, she took my hands and tied them behind my back,” Cockrum said.

Frightened, Shannon crawled toward the hole in the tack room. “My Uncle Mark grabbed me by the legs and then took me out the end of the barn where there was a four wheeler,” Ness said.

She was placed behind her uncle and they sped toward a cornfield a mile away, where he had hidden a motorbike.

“I was always barefoot as a kid, even in the barn, even around the horses. I had my shoes on the back of the four wheeler… and I remember when he started driving away down the ditch, I tossed off the shoes,” Ness said.

ADVERTISEMENT

The chase

Ness’s father, Tim Leppert, heard the screams as he worked in a nearby field, court documents reported. He rushed home and called the Sheriff’s Department. He cut Cockrum free and got her into the shower.

When LaMoure County Sheriff Marke Roberts arrived 20 minutes later, he called two locals to get Cessna airplanes in the sky.

Ness remembers the spear-shaped corn leaves slashing her face as her uncle — who was a fugitive for previous kidnappings — brought her to a hiding spot, a tarp camouflaged with weeds. It was there that she began asking her uncle questions: “Where are we going? What are we doing?”

“He would just say: ‘Be quiet. You get to see your mom soon. You’ll get to see your mom soon.’ And I’m sure that calmed me down,” Ness said.

“The next thing I remember is hearing vehicles. I remember hearing a plane going back and forth so I knew people were looking for us,” Ness said.

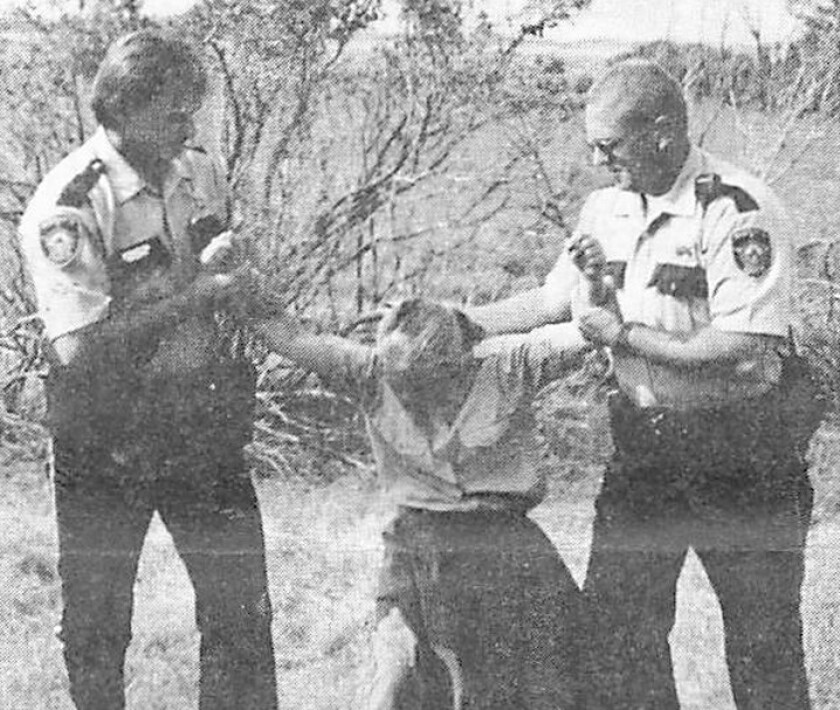

Eventually, Ness's uncle and mother were arrested, and she was rescued. A police officer stayed by her side until her father rode in on his horse.

ADVERTISEMENT

“I remember seeing my dad on my old horse, Cocoa. He had come home as soon as he could, gotten on this horse and he found the shoes. I just remember somebody like handing me up to dad, you know? And just being so happy that I knew I was safe. That look of such concern on his face, which is, yeah, a very, very powerful moment that I will never forget,” Ness said.

The damage

The threat of being kidnapped ended in 1996 after Ness’s mother and uncle — who defended themselves at trial — went to prison, but the feud between the Lepperts and the Winrods left permanent damage on all involved, Ness said.

One brother, Jesse Leppert, was beaten and sexually abused when he was young, and later became addicted to drugs, Ness said. In the end, he “essentially committed suicide by cop,” Ness said.

Ness’s sister, Erika Schumacher, and a cousin escaped the cult under the pretext of enticing Ness to leave, and ended up giving law enforcement enough information to finally spring a raid on Our Savior’s Church property in 2000.

A few of her siblings and family still follow Winrod’s teachings, but Ness has trouble trusting people. Her father became numb, hurt by the loss of his children that he was given sole custody over by the North Dakota Supreme Court.

“He became less loving, less giving and kind. Not to say he’s not a kind person… but you could see it. And, I mean, who wouldn’t be?” Ness said.

“When I was younger, I wanted to believe in Jesus. I would listen to my grandma talk about Jesus and God and all of the things, you know, where women are submissive. Women should never speak over their husbands or men in general, or get in front of a church and preach a sermon or be in leadership roles,” Ness said.

It was when she was testifying in court against her mother that she realized she wanted to become a prosecuting attorney. Today, she works for Redwood County, Minnesota.

“I’m no longer a Christian. I am an atheist, and I blame a lot of what happened to me on religion, on fanatical religion. I look around the world and all I see is religious groups causing problems and not helping, and that’s been since the dawn of religion, so it’s really hard on me,” Ness said.

Once, years after her mother was released from prison, Ness found her near Valley City, North Dakota. Her mother didn’t recognize her.

“I told her I’m here to see if you would like to have some sort of relationship with me. She looked at me and told me that I was not her daughter,” Ness said.

Even though she wishes she had grown up with her brothers and sisters, Ness tries to focus on the good.

“I think it’s better that it happened this way, or I’d be married to some weird, religious dude with 16 children and that’s not a life for me,” Ness said.

'Jayhawk Nazi'

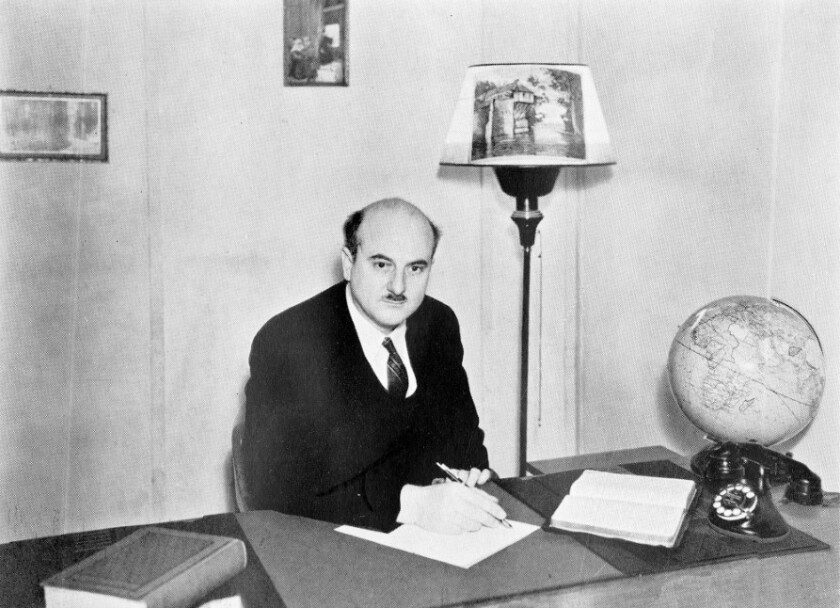

Winrod’s cult didn’t start with him, it began before World War II with Ness’s great-grandfather, Gerald B. Winrod, nicknamed “Kansas Hitler” and the “Jayhawk Nazi” for his antisemitic and white supremacist diatribes over the radio and within publications circulating to more than 110,000 people in the 1930s.

The hatred has lasted for nearly a century covering five generations. Energized by a book written in 1903, later republished by Henry Ford, and acclaimed repeatedly as a forgery throughout its history called “ Protocols of the Elders of Zion ,” Gerald’s hatred for Jews grew after he was invited by Adolf Hitler’s regime in 1935 to visit the Third Reich, according to Barbara Jean Beale in her 1994 Wichita State University thesis.

“Few people today remember Gerald Burton Winrod, but during the first half of the 20th century, he was quite well known throughout the United States and Canada as one of the ‘greatest pulpit orators’ of the fundamentalist Christian faith,” wrote Beale.

Gerald’s “spiritual awakening” began after his mother, Mabel, was “miraculously” cured from an opium addiction and cancer, Johnson wrote, which prompted Gerald — as a teenager — to drop out of school, leave home and go on the road with an itinerant evangelist in the 1910s.

In the 1920s, he began the “Defender Magazine,” and denounced modern trends. In the 1930s, he came across the most "gigantic and diabolical" plots in all history written in the “Protocols of the Elders of Zion,” and he began blaming the world’s problems on Jews.

Gerald passed on his extreme views — at times traveling 15,000 miles around the country in a summer — together with his son, Gordon.

By 1940, he lost a bid for the U.S. Senate in Kansas as a Republican, was tried repeatedly for sedition, and his wife, Frances, divorced him and told authorities he was using his political clout in an attempt to take over the presidency by force, if needed, according to Beale.

“He possibly viewed himself as a ruler appointed by God,” wrote Seth Bate in “Gerald Winrod and the Great Sedition Trial,” published by Wichita State University.

Like father, like son

Like Kahl and Gerald Winrod, Gordon Winrod puppet-ed his father’s hate.

The Winrod Letters are filled with antisemitic vitriol, as well as slanderous attacks on the Leppert family, which continued sporadically until 2002 and Winrod’s incarceration on kidnapping charges.

Court documents included the Lepperts’ defense statements, calling Southeast District Court Judge Richard Grosz head of the “jewdiciary” and the courts a “synagogue of Satan.”

Sharon Leppert claimed in court documents that her former husband, Tim, abused her, and their children, but the court found no evidence of abuse. In the minds of the followers of Winrod’s cult, it was okay to lie, steal or hurt “God’s enemies,” court documents stated.

After the 2000 raid on Winrod’s property, authorities discovered that the grandchildren — ages nine to 16 — barricaded themselves in the secret bunker, the “priest hole.” They were prepared to fight to the death, according to a 2002 article in the Bismarck Tribune.

They had been brainwashed, authorities said at the time.

Eventually, the children came out of hiding and authorities sent some back home to live with their fathers and at least two, Donna and Stephanie Leppert, were sent to mental health institutions, according to Donna’s account, which was published in the Winrod Letters and mailed to North Dakota residents in 2002.

Within her eight-page letter, Donna said she hated her father, Tim Leppert, repeatedly calling him a child molester, and said that her mother, Sharon, and uncle, Mark Leppert, came and freed her.

“The judges stole me from my home where my grandfather cared for me, then they ordered that I be locked in secret mental hospitals to be brainwashed by psychotic Jews for over a year,” Donna wrote.

Gordon was sentenced to 30 years imprisonment for kidnapping six of his grandchildren and keeping them at his rural Ozark County farm to indoctrinate them.

‘Tore apart a whole family’

Ten years into his sentence, Winrod was released . Although he was deeply in debt — owing most of $26 million for actual and punitive damages to Joel and Tim Leppert — many feared Winrod planned to set up his cult once again after Laura and Sam Leppert bought the old Kulm Public School for $5,000 at auction.

Ness alerted the public on Facebook to the sale in 2017, marking the last time media outlets reported on Winrod’s cult.

Winrod visited the school at least once, said LaMoure County Sheriff Robert Fernandes. However, Winrod died a year after the sale, alone in a bathtub on Aug. 29, 2018 in Alabama, and was found several days later, Ness said. He was 91 years old.

The old Kulm Public School building at 105 1st Ave. SW, is still owned by Laura and Sam Leppert, according to Cindy Worrel, county treasurer, but also said the area has been quiet since 2017.

Owners of the building are rarely, if ever, seen, Fernandes told Forum News Service.

“They keep the grass mowed. And in the winter after there are storms they clean the property up,” he said.

Former municipal judge Steven Anderson and his friend, a farmer, Harv Lindgren, sat outside the Kulm Taste Treats & Cafe on Aug. 13, after lunch. Across the street from them was the old Kulm Public School.

Neither man was worried about the cult resurfacing.

"The big concern was that they were going to bring their whole family, you know, about 40 people, up here," said Lindgren.

In the mid-1990s, Anderson received weekly the Winrod Letters.

"It wasn't a good thing for sure. It caused some anxiousness when the town found out the building went up for auction and then bought by them," said Anderson. "They made a big deal of it when he [Winrod] came back, but it was always quiet. He was never an issue."

Ness said she knows that people from the region headed to Kulm to have meetings with Winrod at the time.

And if she hears of any further activity, she will alert the public again.

“I would scream it to the mountains. There’s no way any family should ever have to go through anything like that. It totally tore apart a whole family,” Ness said.