Despite the popular myth playing out on television shows, there is no law requiring a family to wait 24 hours before filing a missing persons report for a minor or adult.

The widely held belief isn’t just false — it’s damaging to missing persons investigations, which require swift action to attempt to locate the individual and determine if they are endangered.

ADVERTISEMENT

“From our experience, making a prompt missing person report without delay allows the best chance for public safety professionals and the public to work together on a common goal of locating the missing person,” Stearns County Sheriff's Office Lt. Zach Sorenson told Forum News Service. “Critical leads are often learned with timely investigations, and that can be hindered by delayed reports.”

The origin of the 24-hour myth isn’t clear — yet multiple missing persons cases covered by The Vault reveal the thought process was alive and active in the 1970s through 2009 in Minnesota.

When 17-year-old Belinda Van Lith went missing in June of 1974, law enforcement waited 24 hours to start their investigation. Despite her leaving a wallet and belongings behind, the original explanation among law enforcement was that Van Lith left willingly.

That theory was reversed a year later when a suspect came into play. Van Lith has never been found.

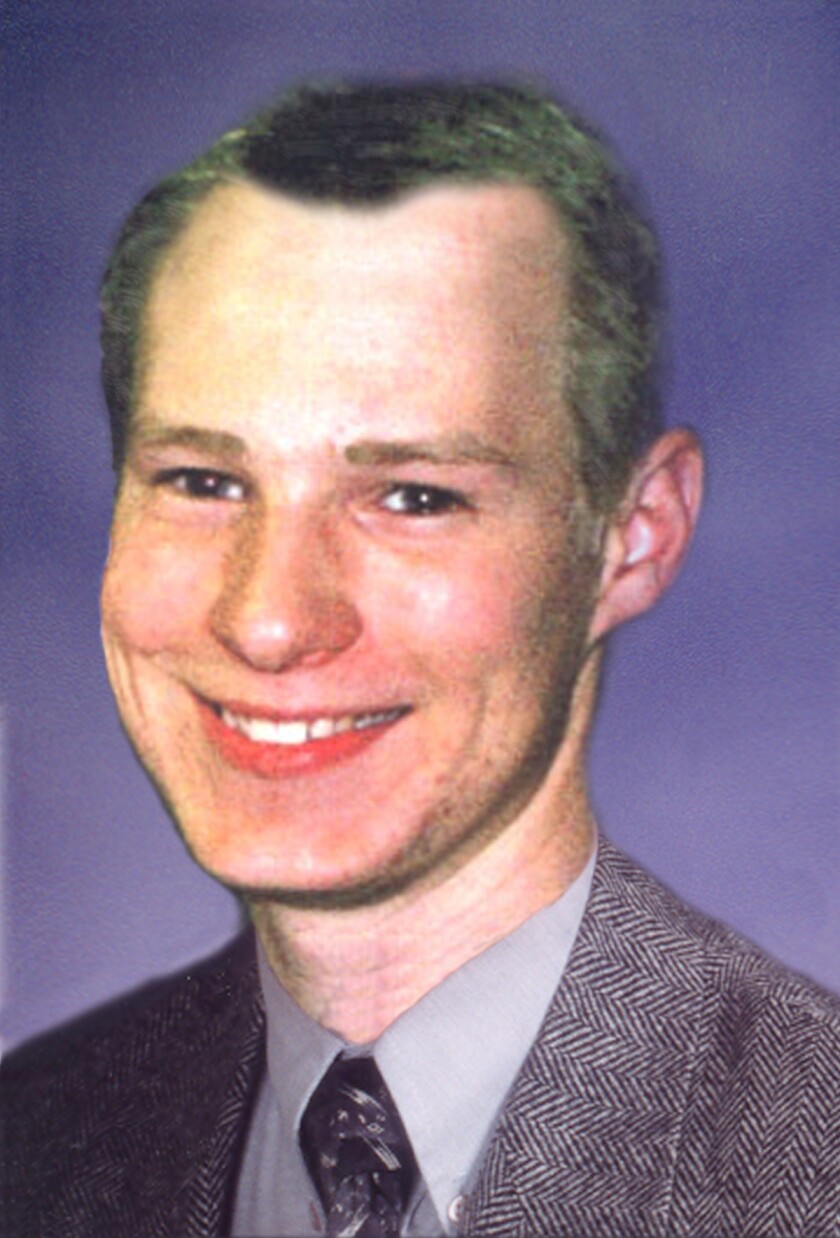

Joshua Guimond was 20 years old when he vanished after attending a party on St. John’s campus near St. Cloud on Saturday, Nov. 9, 2002. After abruptly leaving the party without saying goodbye, his friends discovered the next morning — on Sunday — that he didn’t make it back to his dorm.

Twenty-four hours after he was last seen, his friends reported his disappearance to the Stearns County Sheriff’s Office.

The official investigation did not begin until that Monday, and Guimond has never been found.

ADVERTISEMENT

Brandon Swanson was 19 when he went missing in rural southwestern Minnesota in 2008. Swanson’s vehicle had veered off the road in the early morning hours and he called his parents for help. While on the phone, the call suddenly ended after his parents heard him screaming.

Despite being reported missing by his parents at 6:15 a.m., the investigation was not launched until later that afternoon.

Swanson has never been found.

The list goes on.

Missing person legislation

The nation saw a shift in the way minor missing persons cases are handled, starting in 1990 with the National Child Search Assistant Act of 1990.

The nationwide law requires law enforcement agencies to accept and investigate missing persons cases related to minors without delay.

Six years later, the Amber Alert system was created, which immediately distributes information about missing children.

ADVERTISEMENT

In 2005, the FBI’s Child Abduction Rapid Deployment initiative was launched, providing all law enforcement agencies with the promise of immediate assistance from agents focused entirely on child abductions.

Every state in the country now maintains a missing persons clearinghouse database, available to law enforcement agencies and the public. The databases include both minors and adults who have gone missing.

As the country saw widespread efforts to improve the rapid response to child abductions, law enforcement practices for adult missing persons cases remained the same.

Swanson’s case changed that in Minnesota, though.

His parents successfully lobbied the state legislature in 2009 to adopt a statewide law that requires law enforcement to immediately begin adult missing persons investigations when the report is filed.

Prior to what is now referred to as “Brandon’s Law,” each law enforcement agency was allowed to use its own discretion when investigating adult missing persons reports. The theory to wait was rooted, in part, in the belief that adults have a right to go missing.

South Dakota state law does not explicitly state law enforcement has a legal obligation to immediately launch an investigation. However, the law does require officers to file all missing persons reports into the National Crime Information Center and the missing persons clearing house.

ADVERTISEMENT

“We encourage people to report missing persons to their local law enforcement as soon as possible,” South Dakota Attorney General Communications Director Tony Mangan told Forum News Service.

In Minnesota, state law requires law enforcement agencies to accept missing persons reports without delay. The law is specific in stating what factors do — and do not — need to be met when filing a missing persons report.

State law requires law enforcement agencies to accept missing persons reports, regardless of the jurisdiction in which the person went missing.

Reports must also be accepted regardless of the amount of time that has passed, and even in cases when the missing person is believed to have left voluntarily.

If a missing person is believed to be in danger, law enforcement agencies in Minnesota are required to promptly call in the Bureau of Criminal Apprehension. All cases are required to promptly be reported to the National Crime Information Center and entered into the clearinghouse database.

“If the person is initially determined to be missing and endangered, the agency shall immediately consult the Bureau of Criminal Apprehension during the preliminary investigation, in recognition of the fact that the first two hours are critical,” Minnesota law states.

The same goes for North Dakota, where state law indicates a law enforcement agency is not lawfully allowed to reject a missing persons report on the basis that it’s an adult or if the person has been gone for a short period of time.

ADVERTISEMENT

Minnesota currently has 201 open missing persons cases, according to the National Missing and Identified Persons System. South Dakota is handling 38 open cases, and North Dakota currently has 37 missing persons cases.

Nationwide, there are 25,508 open and active missing persons cases.