ROSEAU, Minn. — A mysterious rock with curious markings unearthed in northern Minnesota in the early 20th century is a mystery no more — unless you really want it to be.

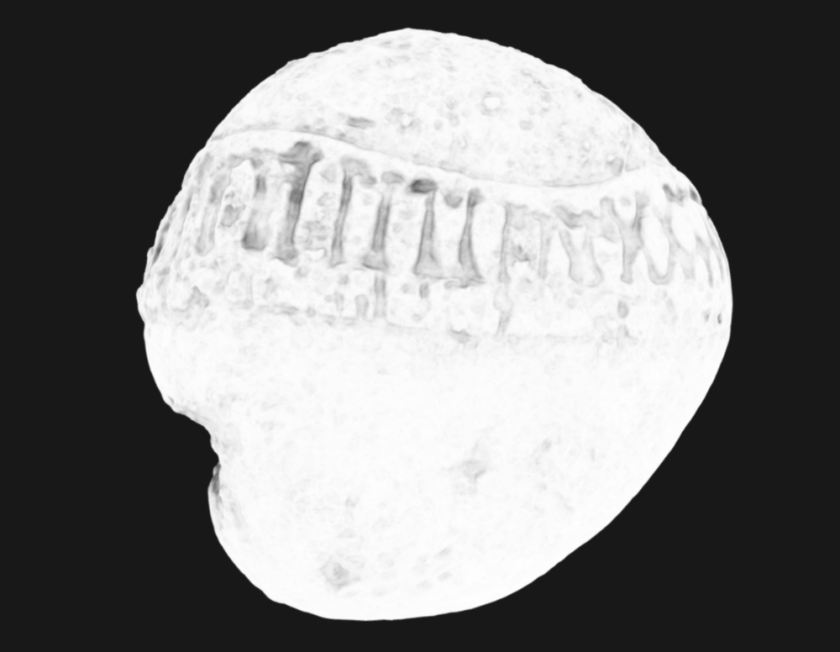

What became known as the "Roseau Runestone" is a small, smooth, golf ball-sized stone with a strip of markings wrapped around it that looks a bit like Viking runic writing. It has fascinated Minnesotans for decades, even as it lay in the archives of the University of Minnesota.

ADVERTISEMENT

Now, according to Erik Moore, head of U of M's University Archives, the central mystery of the runestone has been definitively solved. He documented the stone's decades-long journey and the solution to its enigmatic markings in an article on the U of M's website.

Despite what he says is conclusive evidence that explains the stones, Moore said the stone's markings will likely still continue to intrigue.

"This inch-sized rock has passed through 20 different hands over the course of 100 years, and probably was in the hands of other people years before, and what they thought of it was different for every person," he said. "I think that the interesting story about the Roseau stone is how people interpret and draw their own histories out of something as inert as a limestone rock."

The stone's long journey

The stone was discovered near the town of Roseau sometime between 1916 and 1918 by a man named Jake Nelson, according to a 1928 memo written to former Roseau resident and Minnesota Secretary of State Mike Holm by C.P. Bull, a one-time Roseau County resident and inspector at the Minnesota Department of Agriculture.

The memo is also in the U of M's archives and is a key part of the stone's story, as told by Moore.

According to the Bull memo, Nelson built the first cabin in Roseau County and discovered the stone while working in his garden. A Native American club, arrowheads and hide scraper were also found there.

Sometime after it was discovered, the stone made its way to Holm. From there, it bounced between those interested in it, including John Jager, a Minneapolis architect, and U of M professors Albert E. Jenks and Clinton R. Stauffer, back to the Holm family, with Jager recording each transfer on the small cardboard stationery box that held it.

ADVERTISEMENT

A descendant of Holm later sent the stone to Theodore Blegen, former dean of the University of Minnesota Graduate School. Eventually, it ended up at the university's archives in its humble cardboard box — just one historical artifact among many.

The stone had been an enigma ever since it was discovered. Jenks and Stauffer believed the stone's markings were due to the natural forces of geology. While Moore says Viking rune experts concluded the stone wasn't a rune, Jager seemed convinced it was. He traced the stone's markings on paper and deciphered them as runic writing.

There was additional speculation the Roseau stone could have been a legacy of early Native Americans since it was found in the company of a number of artifacts.

The U of M's archives displayed the stone in 2011 and made it available for view upon request. The stone has gained a minor following among mystery buffs online (including some who think it has Russian markings on it) and it has attracted a steady stream of in-person visitors over the years, according to Moore.

"People interpret what they want to interpret out of them," he said. "Somebody who wants to see a rune in this will see it as obvious examples of people over the past century who have tried to sketch out or draw the letters and make sense of the ribbon itself, and then (there will be) those who see it as more of a natural phenomenon."

The significance of runic writing

If the stone did in fact bear runic writing, it would have been an archaeological sensation, indicating there was European exploration of North America before Christopher Columbus was even born.

Yet there remains no agreed-upon evidence that Europeans such as the Vikings ever explored the interior of North America, although a Viking site was discovered in 1960 at L'Anse Aux Meadows on the Atlantic shore of Newfoundland, Canada.

ADVERTISEMENT

Still, early Scandinavian pioneers in Minnesota and elsewhere in the region discovered, or claimed to discover, a wide variety of artifacts tying Viking travelers to the area.

Perhaps most famous of all of these items is the much-debated and oft-debunked Kensington Runestone, which came to the public's attention in 1898 and remains centrally featured in the Runestone Museum in Alexandria, Minnesota.

The museum also houses a number of less controversial and completely debunked artifacts that early settlers thought might be of Viking origin.

Many historians have placed the origin of this belief in the yearnings of the large wave of Scandinavian settlers who came to the region from the mid-1800s to the early 1900s after it was wrested from its Native American residents.

"Some pioneers sought validation of their ownership of the newly taken land through references to ancient saga claims. By no means were all of these Scandinavian, but latter-day Norse played a major part in this process," wrote author Martyn Whittock in an extensive debunking of supposed Viking artifacts in his book "American Vikings," as excerpted in a 2023 Slate article.

Roseau reclaims the stone

Britt Dahl started working at the Roseau County Historical Society and Museum as a museum assistant and became curator in 2012. The stone was a known item from the area's past, but nobody seemed to know where it was.

"It was known by us, but it was just thought it was lost and destroyed," Dahl said.

ADVERTISEMENT

After the U of M displayed it in 2011, Dahl wrote to the U of M Archives seeking the stone for RCHS's own collection, backing up her request with newly found documentation, and seeking the help of state Rep. Dan Fabian, who represented the Roseau area at the time and is now the town's mayor.

After some consideration, the U of M transferred the stone to RCHS in February 2020. Dahl drove the hundreds of miles from Roseau to the U of M to pick up the stone in person.

"It was in a little baggie, and it was marked 'Roseau runestone,' and there was another arrowhead in there and a box with writings from various first encounters with researchers of it," Dahl said. "It's the size of a golf ball — it's tiny, so it could be easily lost."

The stone was placed on display at the county museum, where visitors are presented with the various hypotheses about the mystery of the stone, and given the chance to draw their own conclusions.

"People are intrigued by it," she said.

The mystery solved

After Moore published his article about the stone on the U of M's website in 2020, he was contacted by a group of geologists and paleontologists from the U of M and elsewhere who said they knew exactly what its markings represented.

ADVERTISEMENT

The stone is an enigma no more.

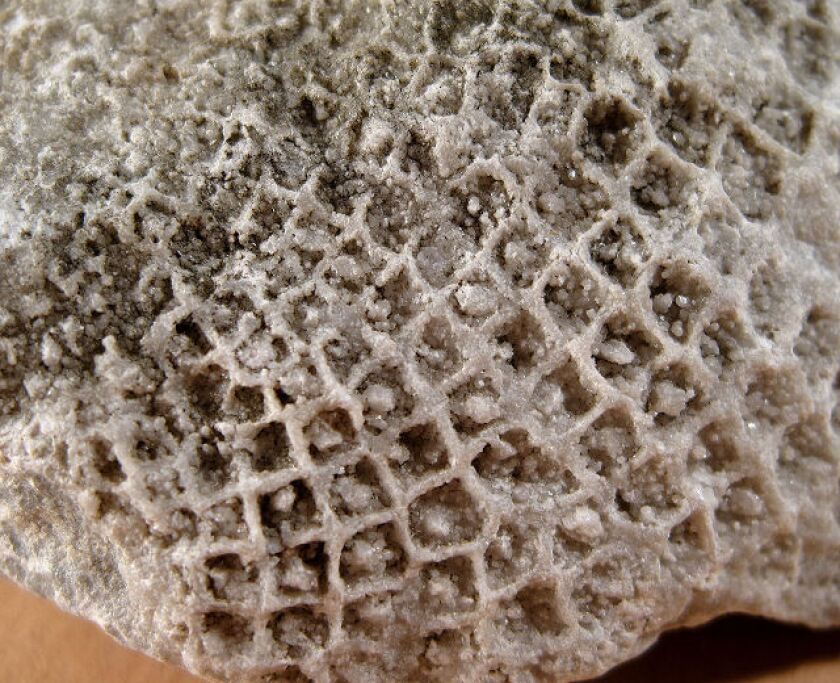

The Roseau "rune" stone is a piece of limestone containing a receptaculites cross-section fossil (Google it for example images). Moore later described this as definitive proof of the stone's identity in an epilogue at the bottom his article.

"The photographic evidence of what these cross-sections look like, having seen the stone in person, seemed to ring pretty true to me," he said.

Receptaculitoids are an extinct group of marine plants that lived between 485-358 million years ago, most commonly accepted to be "calcareous green algae," according to the University of Saskatchewan.

According to the group of scientists who contacted Moore, the fossil-bearing stone was likely carried from Canada via continental ice sheet during the last Ice Age and left behind in what became the Roseau area after the glaciers retreated — just in time to be found and then marveled at for a century.

Moore himself keeps a 3-D printed life-sized replica of the stone in his office, where it's made for an interesting conversation starter.

"It's an enjoyable (story) and I think it has just enough interesting pivots and turns," Moore said. "It may not be true crime, but we used to jokingly say that the stone was cursed, that everybody who's had it has died. But ... we all die at some point."

ADVERTISEMENT