Editor's note: This story is part four of an eight-part series examining the killings of Gilbert Fassett and Eddie Peltier on the Spirit Lake Nation in North Dakota. Veteran reporter Patrick Springer examines both cases and considers a sobering question: Were the men convicted of these murders guilty?

DEVILS LAKE, N.D. — Mark Demarce wrote a letter tipping authorities that he’d heard Werner Kunkel say something he thought they’d find interesting: Kunkel confessed to the brutal unsolved murder of Gilbert Fassett.

ADVERTISEMENT

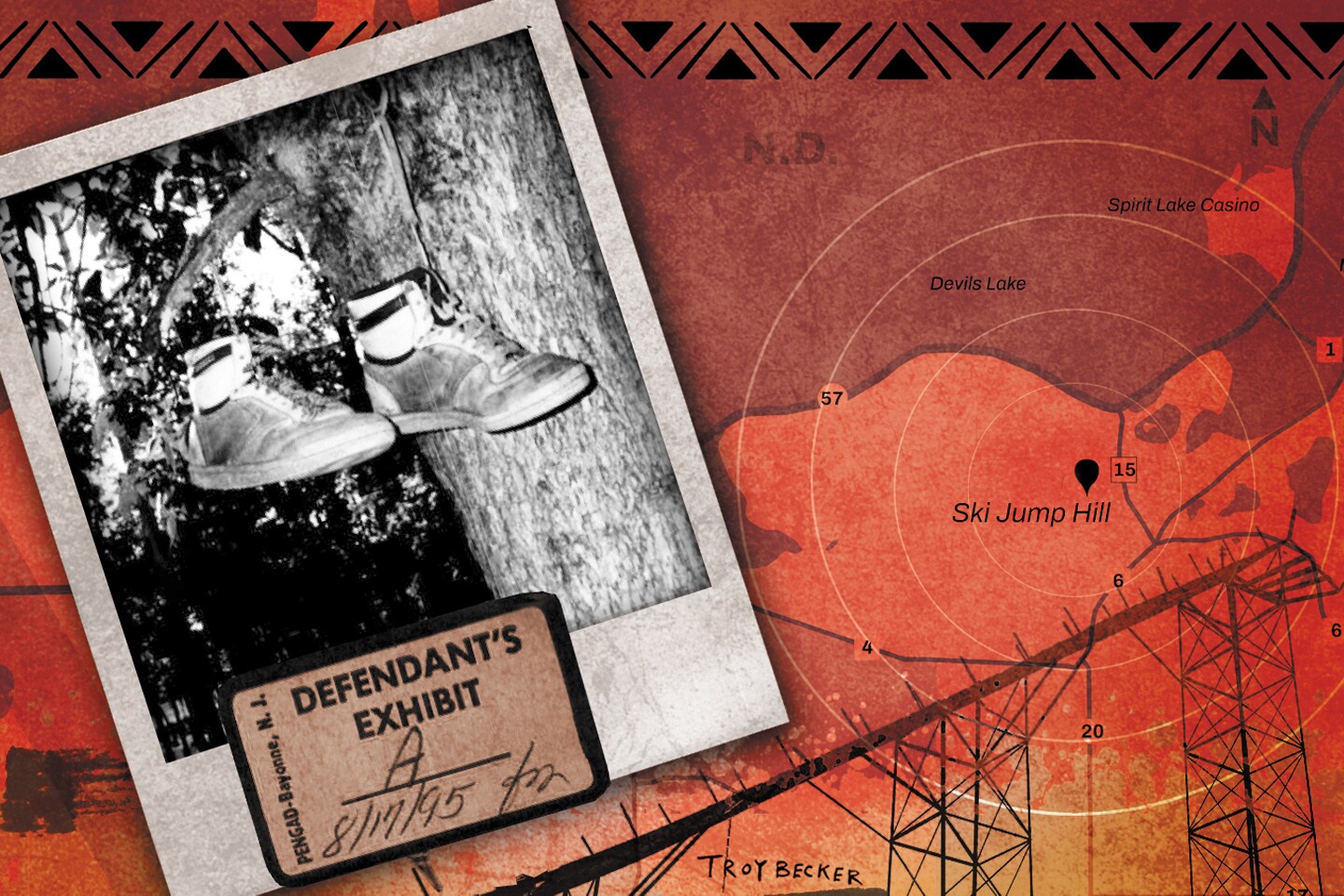

Demarce informed investigators that he could provide details about how Fassett was murdered and how Kunkel disposed of the body, which was found riddled with stab wounds on Ski Jump Hill, a wooded promontory on Spirit Lake Nation along the southern shore of Devils Lake.

Demarce’s letter was written on Dec. 8, 1994 — 11 days before he was scheduled to be sentenced for a felony and misdemeanor that could have kept him behind bars for up to six years.

Before he testified in Kunkel’s trial, Demarce was charged with terrorizing and accused of threatening to kill the family of a law enforcement officer.

In exchange for his testimony in Kunkel’s trial, however, prosecutors later filed for a reduction of sentence, a deal that gave Demarce a sentence of three years, with credit for 176 days served, enabling him to serve just 18 months in the state penitentiary.

Testimony from Demarce — one of four witnesses who testified that Kunkel confessed the murder to them — was important, and not only for the description he gave of the murder.

Demarce’s testimony that Kunkel placed the body on Ski Jump Hill so that Native Americans would be blamed for the murder, and that the murder occurred in Devils Lake, was crucial in giving the Ramsey County state’s attorney jurisdiction for the case.

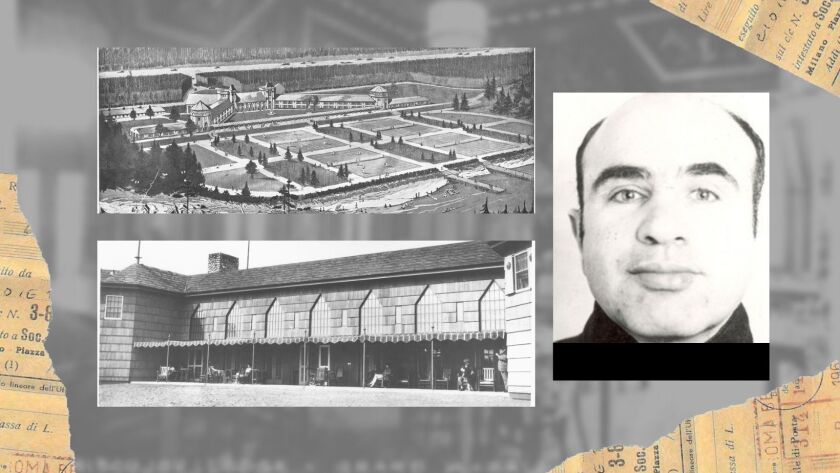

At first, investigators concluded that Fassett had been killed at the scene where berry pickers discovered his decomposing body on Aug. 10, 1986. Federal authorities have jurisdiction for major crimes committed on reservations.

ADVERTISEMENT

The case against Kunkel was circumstantial. There was no physical evidence linking Kunkel to the murder and there were no eyewitnesses. His conviction in 1995 for Fassett’s murder hinged primarily on the strength of the purported confession witnesses.

At trial, Kunkel’s defense lawyer, Todd Burianek, argued that each of the witnesses, especially inmate informants he dismissed as the “pen men,” stood to benefit by testifying for the prosecution.

The prosecutor told jurors that Demarce was the only jailhouse informant who was given a deal for testifying against Kunkel.

“People aren’t getting deals right and left here,” said Lonnie Olson, who was the Ramsey County state’s attorney who prosecuted Kunkel. “People are coming forward.”

Burianek noted that none of the confessions were recorded. “Instead, we have a whole bunch of people making things up,” he argued.

Reliance on jailhouse informants has drawn sharp criticism. Experts and studies have shown that jailhouse informants are often involved in securing wrongful convictions.

“Unreliable and unregulated jailhouse informant testimony is a common contributor of wrongful convictions later overturned by DNA testing and of wrongful convictions stemming from death penalty cases,” according to the Innocence Project, a nonprofit that works to free victims of wrongful convictions.

ADVERTISEMENT

Jailhouse informants who provide information to criminal investigators and prosecutors are “explicitly or implicitly incentivized to do so in exchange for some type of benefit,” an Innocence Project briefing said. “This can include a reduced charge or sentence, financial or other compensation, special privileges while incarcerated or more."

The Great North Innocence Project, based in Minneapolis, is reviewing Kunkel’s conviction.

'I voluntarily gave it up'

Demarce testified at the trial that he and Kunkel had a “one-on-one” conversation in the prison library in August 1993, 15 months before he wrote to authorities offering information.

“So Werner was basically babbling on,” Demarce said. “It was hard to follow him because he kept making different statements. So I wasn’t quite sure where he was trying to lead me."

“He admitted to me in another statement that he had did this homicide in a place in Devils Lake,” Demarce added. “I know nothing about the place; I’ve never been there.”

Demarce told jurors that the murder happened at “some bar” and Kunkel bragged about mutilating the body, which he brought to the “Fort Totten Reservation area.”

Responding to a question from the prosecution, Demarce said he made no personal gain from talking to police. “I wasn’t expecting anything,” he said. “I wasn’t — I voluntarily gave it up.”

ADVERTISEMENT

Then, on defense cross examination, Demarce admitted he asked the judge to reduce his sentence, but denied knowing that a deputy sheriff wrote a letter on his behalf to the judge. The letter was based in part on assisting the deputy in the Kunkel case. Demarce said his lawyer might have written a letter in support of his request.

“And you don’t think that that was done for your testimony,” asked Burianek, Kunkel’s lawyer.

Another penitentiary inmate, Chris Anderson, testified that Kunkel had threatened him while reaching his hand outside his cell bars. Anderson said he saw Kunkel wearing a ring that he recognized as belonging to Fassett, his first cousin, whom he regarded as being “like a brother.”

Asked to explain the threat, Anderson replied: "He said, 'You see this? You're going to get the same thing that Gilbert got.'"

Asked if he ever saw the ring after that, Anderson said no. "I've asked about it a lot, but I've never seen it," he said.

In the defense’s rebuttal case, a pawn shop owner testified that Kunkel pawned a gold lion’s head ring, with diamonds in the eyes, in 1986, and a relative of Kunkel's bought the ring.

In his closing argument, Kunkel’s lawyer noted that the penitentiary was swirling with rumors after Fassett’s mother called to tell Anderson about Fassett’s murder. Anderson made no mention of stabbing, Burianek pointed out, dismissing his testimony as a “big story.”

ADVERTISEMENT

'It bothered me'

Sandra Austin, Kunkel’s former longtime girlfriend and the mother of his two sons, also testified for the prosecution.

Prosecutor Lynn Crooks asked if her going to police had anything to do with testimony Kunkel gave against her husband, Kevin Austin, who was convicted in 1993 of a double-murder near Minot.

In response, Austin said she gave her statement after she was approached by the FBI.

On cross-examination, Burianek asked if it was a coincidence that her husband, Kevin Austin, had been arrested for murder in September 1992 — shortly after Kunkel wore a “wire” and tried to elicit self-incriminating responses from Kevin Austin. Kevin Austin didn’t admit to Kunkel that he murdered Cora and Charley Abernathy in a Minot double-homicide, nor did he deny culpability.

In 2011, 16 years after Kunkel was convicted, a man named Blaine Anderson gave a notarized statement about having an affair with Sandra Austin in Devils Lake during the winter of 1989 to 1990. She was living with Kunkel at the time.

One night, Austin asked Anderson if he knew anything about Fassett’s 1986 murder. He said he told her what he’d been told by a Devils Lake police officer, Peter Belgarde, and a cousin of Fassett’s.

ADVERTISEMENT

“I told her about all the stab wounds,” Anderson said. “She asked me where he was killed and I told her at Lakewood knowing full well it wasn’t there,” a reference to a subdivision near Devils Lake.

“But I was feeling uncomfortable about her questioning and told her I didn’t want to talk about it anymore. She tried to bring up once more asking me where in Lakewood Gilbert was killed and I told her I wasn't sure. It was none of her business and it bothered me to talk about it.”

During the trial, prosecutor Lonnie Olson repeatedly said details about the case were withheld from the public, and argued that Kunkel’s purported confessions contained information that only the killer could have known.

Under cross examination, Sandra Austin acknowledged that she wanted to discredit Kunkel through her testimony. Also, she admitted that she didn’t mention Kunkel’s confession of murder when she wrote a letter to the Parole Board asking to deny his parole, or in any of several protection order applications she filed.

'Something like that'

When Kunkel was awaiting trial, Nicholas Elston was paired with him in a jail cell in Devils Lake.

The following day, May 11, 1995, Elston was talking to an agent of the North Dakota Bureau of Criminal Investigation and a Ramsey County deputy sheriff, claiming that Kunkel had confessed to him.

“Did Werner tell you how he killed Gilbert?” BCI Agent Cindy Graff asked Elston, according to a transcript of the interview.

“No, ah, he says, everyone, they had statements from everyone else that he was strangled or stabbed, and shot in the head, you know, all this stuff.”

Elston added that Kunkel said his only role in Fassett’s killing was to “put a cord around his neck” and that the murder took place in front of a bar.

After Graff asked if Kunkel had killed Fassett by putting a cord around his neck, then asked if Kunkel told him how Fassett was stabbed repeatedly, Elston’s account became more detailed.

After first telling Graff that Kunkel didn’t tell him how Fassett was stabbed repeatedly, Elston then said: “Someone had a cord around his neck. And, but he did tell me he was stabbed.”

At the trial, Elston testified that Kunkel’s jailhouse confession was “all voluntary on his part.” He said the confession came out over a few days, little bits at a time.

On cross examination, Burianek noted that the two had never met before and asked, “And all of a sudden, he started spilling out all this information?”

Elston replied, “Yeah, something like that.”

Kunkel was moved into the same area in the jail where Elston was being held. The two spoke of the Fassett murder over card games, Elston testified. Elston said he had been with Kunkel “about a day” when Kunkel started confessing.

Less than a year after Kunkel’s conviction, in a letter dated March 25, 1996, Doug Mattson, then the Ward County state’s attorney, wrote to Lonnie Olson, who prosecuted the Fassett murder.

Mattson enclosed a copy of a letter from an inmate at the county jail, John Shoecraft, informing Mattson that “Nick Elison” — an apparent reference to Nicholas Elston — said he “framed Warren Conclin” while the two were in lockdown together.

“Apparently, this may be meant to be Warner Kunkel since it is alleged that the crime had occurred somewhere near Devils Lake,” Mattson wrote, misspelling Kunkel’s first name.

“I don’t know what to make of it, but I thought I should bring it to your attention,” Mattson’s letter to Olson concluded.

'Not given a fair trial'

After Kunkel was convicted in 1995 of Fassett’s murder, Mark Demarce returned to the witness stand to testify — this time on Kunkel’s behalf.

In May 2011, in Kunkel’s second case seeking a new trial, he was acting as his own lawyer and called Demarce as a witness.

Kunkel, who had since changed his name to Werner Rümmer, asked Demarce if he believed he had received a fair trial.

“No, I believe that you were not given a fair trial,” Demarce said.

Asked to explain, Demarce said he was studying his statements before testifying in the murder trial “and keeping it fresh in my mind.”

Two other inmates, including Elston, “were more or less feeding off of what my statements were at that time in the county jail,” Demarce said. “So, yeah — I feel that — that you were given an unfair trial.”

He added: “I believe they were fishing to gain some sort of proof they just went up to the state prosecutor. But then that’s just my opinion.”

On cross examination, Demarce said his trial testimony was truthful and wouldn’t alter his testimony.

During the evidentiary hearing, the judge stopped Rümmer, asking him to get to the point rather than rereading trial transcripts.

After a brief recess, Rümmer, who didn’t testify in his earlier trial, took the witness stand and asked himself, “Did you ever confess to anybody that you killed Gilbert Fassett?”

Answering his own question, Rümmer concluded his testimony, “Absolutely not.”

Yet another trial witness who said Kunkel confessed was Fred Nakken, who described himself as a friend of Kunkel’s.

Nakken testified that the two men were drinking in a bar when Kunkel confessed to the murder, demonstrating how he repeatedly stabbed Fassett.

Although not in custody at the time he was interviewed by authorities, Nakken was often in trouble with the law, with a drug habit and a record of burglaries, said Douglas Broden, a lawyer who argued that Kunkel should have a new trial.

As a result, Nakken could have wanted to seek favor from authorities, much like Nicholas Elston. Broden said he knew both men when he provided indigent criminal defense services.

Of Elston, Broden said, “In my opinion, he would say anything if he thought he could get anything out of it. His name appeared frequently on investigative reports when I was doing that kind of work.”

Despite verdicts that rely on testimony from dubious witnesses, judges are very reluctant to overturn a criminal conviction, Broden said.

“Courts value the finality of a court decision, especially in a case where a jury decides something,” he said. “They value that over accuracy.”

The North Dakota Supreme Court rejected Kunkel’s appeal, which argued that there was insufficient evidence to support his conviction.

In a unanimous decision, the justices noted that after “reviewing the evidence in the record in the light most favorable to the verdict,” jurors could reasonably conclude that Kunkel was guilty. Justices also rejected arguments that most of the evidence was circumstantial and that witness accounts were inconsistent and not credible.

“The record also shows that Kunkel made several admissions implicating himself in Fassett’s killing,” and the court cited testimony by witnesses including Demarce and Elston.