BEMIDJI, Minn. — Careful not to wake her husband, who according to multiple newspaper accounts had already beaten her three times on May 26, 1983, Lucile Tisland slowly slid her hand under his pillow. In an adjacent room, her surviving three sons slept.

Weather statistics reported a full moon while he slept inside the mobile home, the same place where about two months earlier, their 9-year-old son, Mark, died after a two-year struggle with encephalitis. At times, she spent 16 hours a day with him as he slowly went blind and deaf, watching him waste away to under 25 pounds.

ADVERTISEMENT

Not once did her husband, Robert Tisland — a former Baptist preacher who became the director of Faith Baptist Christian School in Bemidji, Minnesota — ever sit with his dying son. Instead, he whipped him when he whimpered late at night, according to a March 7, 1984, news article in the Minneapolis Star Tribune.

Lucile still loved her husband, but in her mind, she had no other choice, according to newspaper archives. Her hand touched metal under her husband’s pillow. Carefully, she wrapped her fingers around the hilt of a .22-caliber pistol he always kept loaded.

Still sleeping, the man she once called “honey pot” was now a threat to her sons. To him, she was simply his “heifer,” whom he beat regularly.

“I reached for the gun under the pillow … He opened his eyes and he acted like he was going to sit up,” Lucile testified during her trial.

Earlier that day, he was “carrying on like a crazy person. His eyes were wild. I had never seen him like that. He said he was at the breaking point, that I would not see another morning and that he was going to kill me,” Lucile later testified in court.

She pulled the pistol out. She pointed it at him. Robert began sitting up.

No more words. She was scared for her own life. She was scared for the lives of her three children. She no longer recognized the man she met in college in 1970, the man who had later groomed her into becoming a submissive housewife, the man who taught her his failures were her fault.

ADVERTISEMENT

“I sat up and I shot him,” Lucile testified.

The first bullet hit him in the neck. A second round struck her husband in the chest, according to multiple newspaper reports.

The gunshots woke her sons inside the mobile home. No questions. She took her boys to a friend’s house, returned home and called the sheriff’s office.

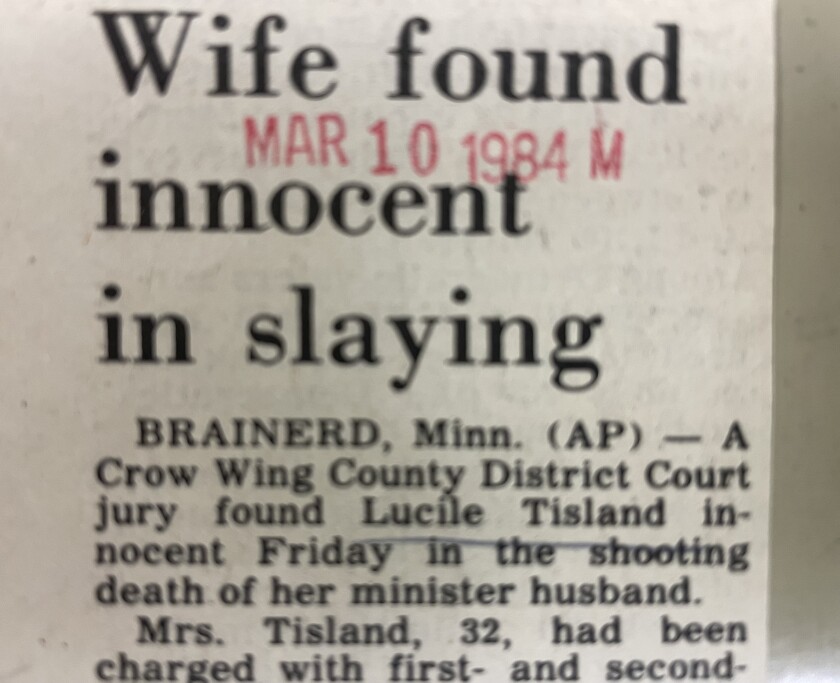

Nearly a year later, after a lengthy trial, where Lucile and her sons testified, the 10-man and two-woman jury sequestered for five hours of deliberations. The verdict on March 10, 1984, made headlines across the country.

“Battered wife acquitted in husband’s slaying,” a UPI headline reported. “Tisland case may have set precedents,” headlined The Forum on March 13, 1984.

‘There is justice’

Robert Tisland’s murder was the second time a wife shot her husband in the Bemidji area in less than a year. On Dec. 31, 1982, a 26-year-old woman named Ann Peters killed her husband, Kevin Peters, by shooting him in the head with a .22-caliber revolver while he slept.

ADVERTISEMENT

Like Tisland, she claimed her husband was abusing her, and for 14 days in 1983, Tisland and Peters were cellmates in Beltrami County Jail, newspaper archives show. Both women shot and killed their sleeping husbands. Both were from Bemidji.

Kevin died at St. Luke’s Hospital in Fargo, North Dakota, two days after he was shot.

Unlike Tisland, however, Ann was found guilty and sentenced to 10 years imprisonment, the Winona Daily News reported.

In a news interview, Peters didn’t resent that Tisland was acquitted and she was serving a prison sentence.

“There is justice after all,” Peters told reporters in 1984.

She met Kevin while studying history at Central Michigan University, and the beatings didn’t start until after they were married in 1980.

“I was raised Catholic and in a family tradition in which the man should be the master of the house. He called me dumb … I started to believe him. I kept my mouth shut because I felt that I deserved it,” Peters told the Star Tribune.

ADVERTISEMENT

On the day she murdered her husband, she woke up from a nightmare of being beaten. She wanted to drive away, but their car wasn’t reliable. She picked up the handgun, intent on killing herself.

Then she heard a voice telling her that her husband deserved to die, according to one newspaper report.

Peters’ memory of the shooting was vague, but she rushed away when she saw blood on her hands. She resisted an insanity plea because she feared mental institutions and a part of her believed she “deserved to be punished,” she said.

“I still feel guilt over what I did. I must admit that although I’m not glad he was shot, I’m not sorry he’s gone.”

Peters and Tisland didn’t speak much while they were cellmates.

“It was pretty raw with Lucy then, and I’m still not really comfortable talking about it. I felt so sorry for her. We each knew what the other had gone through, but in jail, I learned to respect other people’s privacy,” Peters said.

ADVERTISEMENT

The precedents

The matricidal murders in Bemidji prompted thousands of protesters to take to the streets to protest rape and violence against women in America. Carol Ball, vice president of the Bemidji chapter of the National Organization for Women, told a St. Cloud Times reporter that women would not allow society to suppress them any longer.

Hundreds of women gathered in downtown Minneapolis on Aug. 6, 1983, in the Take Back the Night March. On the same day in Bemidji, demonstrators gathered on the lawn of the Beltrami County Courthouse to show support for Tisland and Peters.

“The laws have changed to protect victims … But attitudes change so much more slowly. They are still blaming the victims,” Nancy Biele, a Bemidji march organizer, told the Grand Forks Herald.

The Tisland case also opened wide the doors of spousal and child abuse, according to an editorial published in The Forum shortly after Tisland’s acquittal.

Historically, wives were considered chattel and could be beaten at will, the editorial reported. Adhering to the biblical principle of sparing the rod spoils the child, children were whipped severely “behind closed doors, and no outsider could be expected to intervene in favor of the abused,” the editorial stated.

“The Tisland case helped to brighten another ray in the emerging sunlight of female equality with men. The lesson to be learned is that society no longer tolerates this kind of treatment. Victims are encouraged to seek help,” the editorial stated.

The Tisland trial was also the first experiment conducted by the state to allow media cameras into courtrooms, according to The Forum. Journalists were not allowed to point the cameras toward jurors or children or objecting witnesses, and attorneys said the presence of media and cameras was not distracting, according to an editorial published by The Forum on March 15, 1984.

ADVERTISEMENT

‘A private hell’

Family abuse experts like Lynn Powers, director of the Wilder Child Guidance Clinic in Maplewood, Minnesota, testified during Tisland’s trial that the reverend’s violence produced a “traumatic bond” in the family that led to Lucile murdering her husband while he slept, according to a March 8, 1984, news report in The Forum .

A traumatic bond can be common in families that are isolated, under stress, and dominated by an unpredictable and violent adult, she said during the trial.

Wearing a frilly white dress, twisting a handkerchief in her hands, Lucile took the stand in her own murder trial. She testified that her husband beat her whenever she strayed from being submissive. He dumped his food on the floor and ordered her to clean it up. He blamed the death of their son, Mark, on her sins, according to The Forum’s article.

He shot the family dogs in front of their children, boarded up a rented house from the inside when he thought people were after him, and paced the floor at night with a gun he kept loaded.

He threatened to kill her the night she shot him, the Minneapolis Star reported.

“I was raised that you don’t leave your husband. And I was scared of leaving because he had threatened that if I ever left, he would come and find me and the boys, and all that would be left would be pieces,” she told the court.

Robert Tisland’s 12-year-old son, Robert Tisland Jr., also testified, saying that his father kicked, slapped and choked him and that his mother was beaten frequently, especially when she tried to intervene.

Slender and blond, Robert Tisland Jr., spoke softly during his testimony, describing mixed feelings he had for his father. When he was younger, his father played basketball and softball with his sons. He took them fishing, and occasionally allowed them to shoot the .22-caliber pistol that he kept loaded under his pillow or between the mattress and the box spring of his bed.

He was especially worried about his younger brother, Jeff Tisland.

“It always hurt so bad that he couldn’t stop crying. Dad sometimes spanked him again,” Robert Tisland Jr. said in court.

Jeff confirmed his brother’s testimony during trial, saying there were times he feared his father would kill him.

“Once he had thrown me down on the bed and pounced on me. She (his mother) said, ‘Stop choking him.’ He said, ‘Get out of here, woman. I’ll take care of you later,’ ” Jeff said in court.

The prosecution argued during the trial that Lucile was jealous of a 14-year-old girl her husband admitted to hugging and kissing during counseling sessions, according to a March 8, 1984, news article.

But she was never jealous; it was common for girls and women to develop crushes on pastors, she testified.

Lucile loved her husband deeply, she said during her testimony.

Lucile’s lawyer, William Mauzy, was pleased with the jury’s verdict, saying that Lucile lived in a “private hell” for 12 years as the victim of her husband’s abuse. The case also showed that jurors were willing to accept battered spouse and battered child defenses in court.

After the trial, Lucile planned to return home to her parents in St. Paul and continue being a mother to her boys. Lucile died in 2002, according to her obituary. The epitaph on her headstone reads: “Beloved mother and friend.”