DULUTH — Until now, making a straightforward movie about Bob Dylan has felt impossible, or at least inadvisable.

Given that Dylan remains an enigma even after six decades of being a world-famous rock star, it has seemed that looking straight into his face could only yield more mystery. Todd Haynes' "I'm Not There" (2007) had six actors take turns in the role, as if only by deconstructing the artist could a dramatization possibly begin to approach him.

ADVERTISEMENT

James Mangold's "A Complete Unknown" (opening Dec. 25), a well-crafted and astonishingly conventional biopic, is thus distinctive just by existing. The director and his enthusiastic star, Timothée Chalamet, assumed a daunting task when they set out to explore how the much-mythologized musician moved as an actual presence among other human beings while making the most influential artistic pivot of the rock era.

Over the four years depicted in the film, 1961-1965, Chalamet increasingly retreats within the Dylan persona: hiding behind shades, adopting an ever more cramped style of speech, visibly distrustful of people surrounding him. From the beginning, though, Chalamet plays Dylan's affect as a proto-punk dare.

This Dylan is alternately charming and abrasive, aware of his talent and trusting that listeners will fall into fascination when he opens his mouth to sing. One of Chalamet's best-observed moments comes when Joan Baez (Monica Barbaro) first calls him out for being a jerk. Delivered after a pregnant pause, his shrugging response plays as at once entirely honest and profoundly disingenuous, implying that the question of whether he's being kind to his own bedmate is too boring to waste time on.

The movie appreciates the manipulative qualities of this performance (both Dylan's own performance of himself, and then Chalamet's take on the same), but Mangold steers clear of the darker corners biographers have chronicled. With a screenplay by Mangold and Jay Cocks, the film is unsurprisingly sympathetic to Dylan, who consulted on the project. It's equally predictable that "Sylvie Russo" (a fictionalized Suze Rotolo, played by Elle Fanning) comes across as a patient saint, and that Baez is accorded a righteous comeuppance after Dylan humiliates her.

In fact, "A Complete Unknown" is somehow sympathetic to nearly everyone in Dylan's orbit, including positively cuddly portrayals of Albert Grossman (Dan Fogler) and Bobby Neuwirth (Will Harrison). Dylan's manager and road manager, respectively, enabled some of the musician's least lovable behavior. Here, though, they come across as stalwart friends who share Dylan's vision — unlike, say, Pete Seeger.

A quietly amusing Edward Norton plays the folk traditionalist who supports Dylan before being disappointed by the younger artist's turn toward abrasive experimentation. Although Mangold does not omit Seeger's temptation to literally ax the power when Dylan "goes electric" at the 1965 Newport Folk Festival, the onetime Weaver emerges as deeply principled, the knowing face of a musical movement that had the temerity to value tradition.

Thanks to the mythos surrounding Dylan's transformation, there are few musical movements assigned a more thankless status in our collective memory than the '50s and '60s folk revival. Even in "A Complete Unknown," with its almost-cool Seeger and its no-bull Baez, the Newport audience greeting Dylan is portrayed as uniformly intolerant of Stratocaster sound, burying Dylan and his band under a hail of debris.

ADVERTISEMENT

The reality was somewhat more nuanced, but Mangold understands that his imperative is to make a compelling movie, not to fine-tune music history. Chalamet acknowledged as much after a Minneapolis screening of the movie earlier this month.

"I took the rock and roll history point of view about a lot of scenes," said the actor. "Jim had his eye on the story."

Thus the film's various creative liberties, which range from folding the "Judas!" moment into Dylan's Newport set (the infamous heckle actually happened the following year, in Manchester) to a concocted TV appearance with Seeger and a fictional bluesman played by Big Bill Morganfield (son of Muddy Waters).

The latter scene turns into one of the movie's comic highlights and makes the pointed musical argument that Dylan's electric blues turn honored American roots music just as surely as Seeger's sincere singalongs.

Mangold's "Walk the Line" is an oft-cited forerunner to "A Complete Unknown." Joaquin Phoenix played Johnny Cash in that 2005 biopic, which boiled the Man in Black's story down to a single relationship at the root of his entire psychology: not Cash's relationship with June Carter, but with his father.

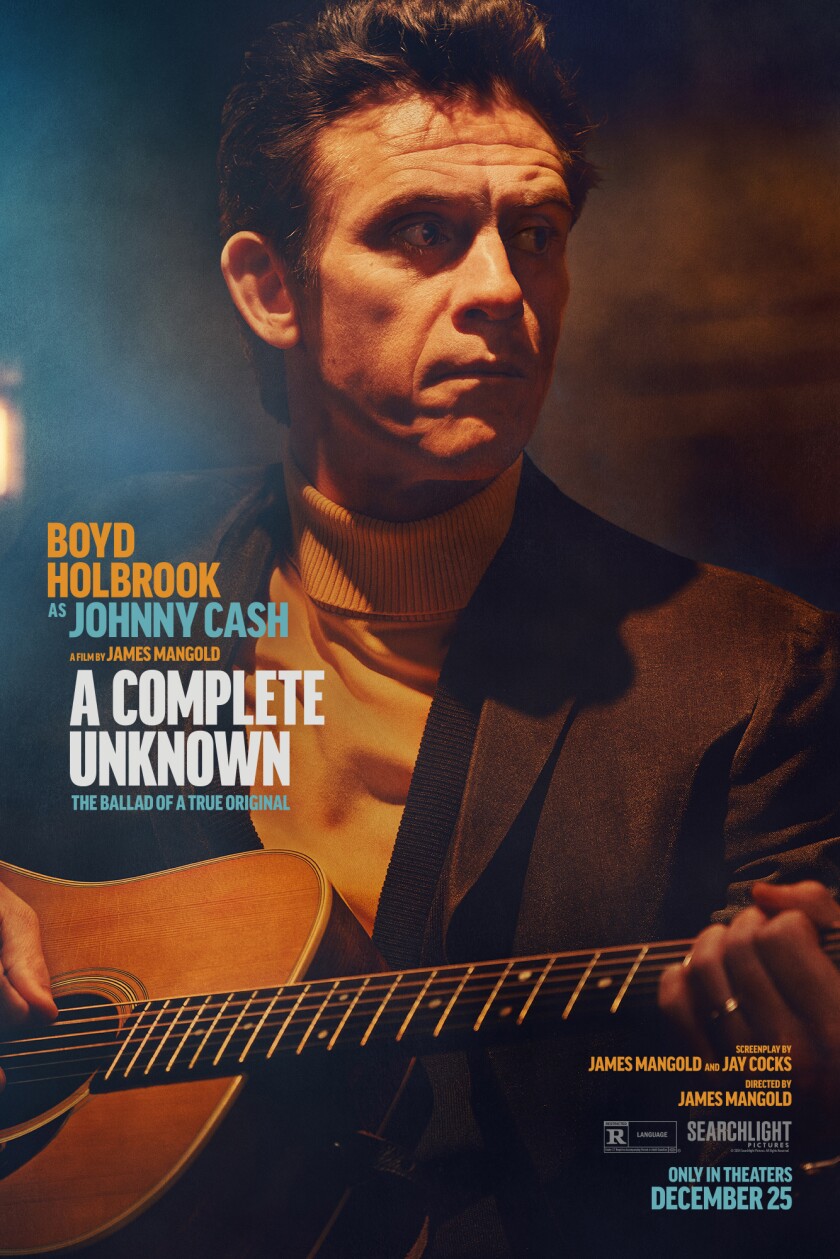

Gratifyingly, "Complete Unknown" gives Dylan a little more freedom of movement — and does the same with Cash, played by a rambunctious Boyd Holbrook. Dylan's own family members intrude only in the form of a scrapbook mailed from Hibbing ("Are those his friends from the circus?" asks one character, lacerating Dylan's outlandish obfuscation of his past), and Mangold holds back from trying to explain the ultimate source of Dylan's musical genius.

Every movie about a great artist has to make an argument about the nature of artistic inspiration, and the vision that emerges here is bracing. For reasons the film doesn't attempt to fathom, the Dylan of "A Complete Unknown" is born with the ability to write world-changing songs. That forecloses a normal life, since if Dylan is to chase his unparalleled muse, he can't meet the expectation to behave like a normal human being or even like a normal artist. He's constantly trying to outrun the narratives people want to pin on him.

ADVERTISEMENT

Chalamet's exceptional performance melds well-studied technical execution with a sense of vulnerability, of being alive to the moment. We truly believe Dylan is making this all up as he goes along, and more importantly, that he believes it needs to be that way.

Where "A Complete Unknown" falls short is in connecting the dots between Dylan's artistic career and his personal life. When Dylan and Sylvie part ways, we're left wondering why. Baez is the stated reason, but given how sour that relationship has already become, it would seem that something bigger is going on.

Could Dylan ever have been vulnerable enough to forge a lasting relationship, or was the split really just a consequence of ordinary rock-star entitlement?

The movie could have delved more deeply into Dylan's complex personal and professional relationship with Baez, instead of rounding historical bases that aren't particularly illuminating. Mangold didn't make Chalamet and Fanning recreate the "Freewheelin' " cover, so why do we need a dramatization of Al Kooper (Charlie Tahan) sneaking onto the organ for "Like a Rolling Stone"? Did the Cuban Missile Crisis really need to be introduced as a plot point in Dylan's romantic history?

Distractions aside, Chalamet's sensitive and alluring performance makes "A Complete Unknown" an absorbing exploration of the costs of creative commitment. The question the film leaves unanswered — the true "unknown" — is just how much of a cost Dylan really paid.

The film implies that what Dylan now calls the "fiasco at Newport" pushed the artist to the breaking point, and seems to point toward the 1966 motorcycle accident that temporarily sidelined the musician and led to a rootsy retrenchment.

Was the newly electric Dylan only hurt as a frustrated artist, or was the pain personal as well? The movie makes clear that Dylan couldn't keep Sylvie or Joan, but doesn't have as much to say about what exactly he might miss from those relationships — or, for that matter, from his fractured relationship with the folk scene the movie brings so lovingly to life.

ADVERTISEMENT

In the end, Dylan's inner life remains opaque, which indeed feels authentic. Chalamet's Dylan is funny, smart and magnetic, with a devotion to his music that goes well beyond any care he shows to a human being (except, perhaps, Woody Guthrie).

When Dylan tells the bluesman that taking his guitar would be like taking his woman, it may be the most revealing dialogue in the film.