MINNEAPOLIS — On a subzero Sunday night in December 1963, Auburn “Pat” Hare held a hot pistol in his hand.

His companion, Mrs. Agnes Winje, 49, lay bleeding on the floor of the south Minneapolis apartment she and Hare, 32, shared. He had shot her, several times.

ADVERTISEMENT

A neighbor had called the police to report a domestic disturbance.

Officer James E. Hendricks responded, coming through the front door of Winje's apartment. Hare shot Hendricks three times, knocking him to the ground. Hendricks’ partner, Patrolman Charles Langaard, was a few paces behind, and he shot Hare.

Hendricks died on the way to the hospital; Winje would survive for a short time before she, too, died.

Hare, described in news reports as a local window cleaner, would recover from his injuries, but would spend the rest of his life behind bars thanks to his violent Dec. 16 spree.

In the coming weeks, it was learned that Hare was not only a window cleaner, but an accomplished guitarist. In fact, as Pat Hare, he had played guitar on some of the most formative blues songs of the 1950s, and had developed an innovative and influential style that presaged rock-and-roll and heavy metal music.

But his legend would be forever tied with a song he recorded in Memphis, Tennessee, nine years earlier. It seemed that Hare predicted his fate — and his crime — in a malicious-sounding track with a devastating title: “I’m Gonna Murder My Baby.”

A frightening, futuristic recording

At Memphis’ iconic Sun Studio on May 14, 1954 (three weeks before a teenaged Elvis Presley was scheduled for his first recording session), the order of the day was to make a couple sides with blues harmonica player James Cotton.

ADVERTISEMENT

Cotton’s guitar player, a talented 23-year-old called Pat Hare, was to follow with a recording of his own.

Hare was suitably warmed up after playing behind Cotton, easily laying down crunching, distorted power chords in the song “Cotton Crop Blues.” The piercing guitar sound would become as influential as it was frightening. Hare had just given everyone in the room a glimpse into the future of rock music.

Now, depending on the story you believe, either Sun Records impresario Sam Phillips or divine inspiration brought the tunes to Hare that day.

But what is a fact is that Hare plugged in his guitar, amplifier buzzing, and sat back as the piano came in. Hare met the melody and then laid down a thick, heavy chord, drawling the first lines:

Good morning judge, and your jury too

I’ve got a few things that I’d like to say to you

I’m gonna murder my baby

Yes, I’m gonna murder my baby (I just thought you’d like to know judge)

Yes, I’m gonna murder my baby

Don’t do nothing but cheat and lie …

With its heavy, deliberate pace, Hare unleashed an apocalyptic three minutes of blues. To match the brutal sound came vivid and violent lyrics, the tongue-in-cheek boasts this raw music needed.

ADVERTISEMENT

The menace of Hare’s guitar was cut by his high-pitched, countrified vocals … a chaotic mix of mayhem and mirth more fitting a comic book villain than a popular music singer.

Phillips decided not to release Hare’s song, for whatever reason (it would be released years later on a black-market record). But the bluntly named “I’m Gonna Murder My Baby” would haunt Auburn "Pat" Hare for the rest of his life.

‘Nagging’ before shooting

The incident would unfold quickly.

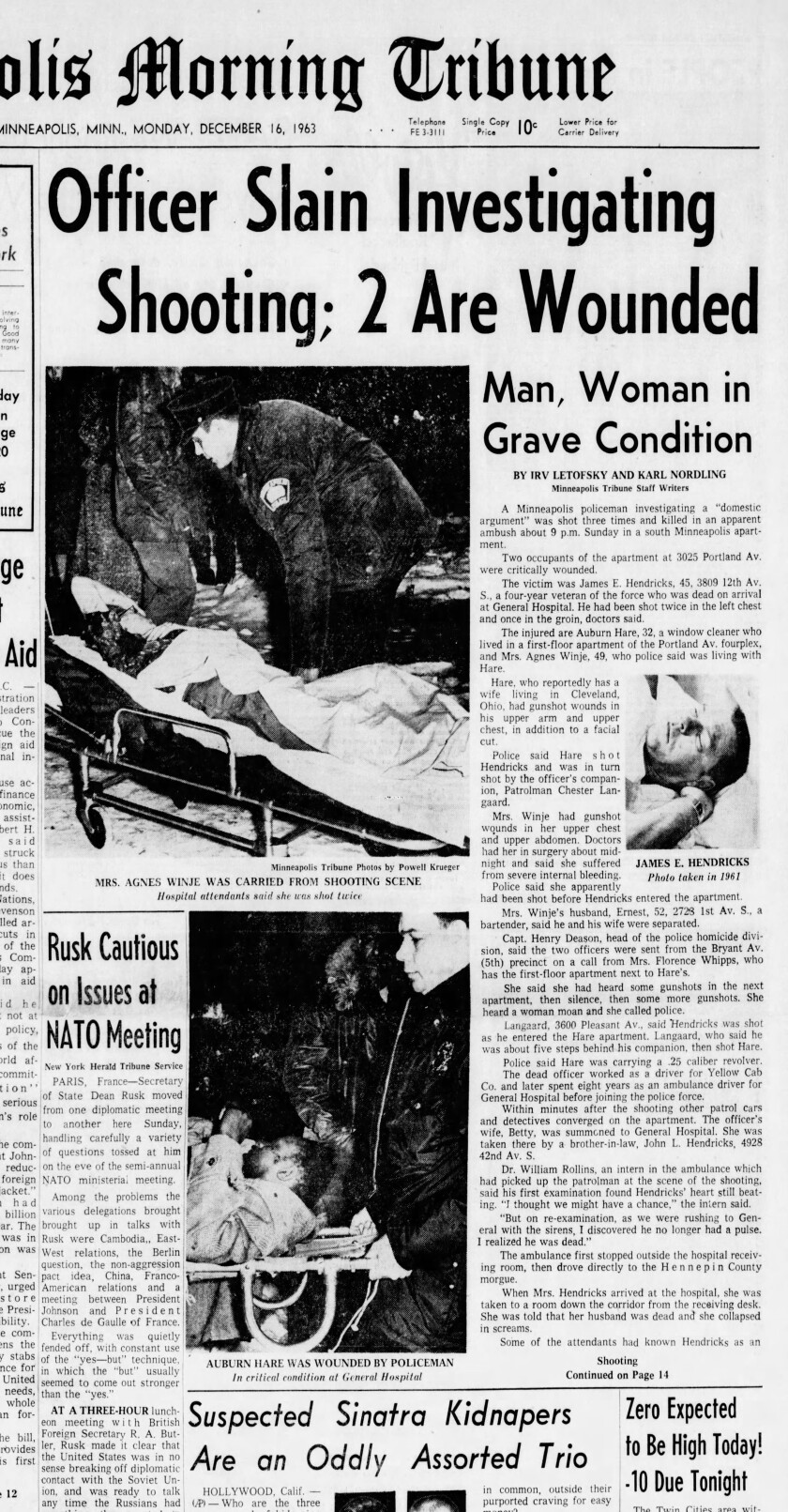

It started with a “domestic quarrel” at about 9 p.m. on Sunday, Dec. 15, 1963, according to contemporary reporting in the Minneapolis Morning Tribune.

Agnes Winje, separated from her husband, had rented an apartment at the fourplex at 3025 Portland Ave. two months earlier. She and Hare were an item, and he was living with her, for all intents and purposes.

According to police statements and court testimony at the time, a female acquaintance had been driving Hare to friends' homes and bars for drinks. Hare came back to the apartment, and that's when Winje started "nagging" him, he told police.

ADVERTISEMENT

He fired several shots into the kitchen wall of the first-floor apartment “just to scare her,” Hare later said. Police would later find five bullets lodged in the kitchen wall.

But when that didn’t stop her “nagging,” Hare shot her several times with a .25 pistol. Winje suffered gunshot wounds in her upper chest and upper abdomen.

A neighbor heard the shots and a woman’s moan, and quickly called police.

When Hendricks and Langaard arrived, Hare met them with gun in hand. Winje was on the floor suffering severe blood loss.

Hendricks, armed with a shotgun, said, “Give me your gun,” Langaard recalled, and Hare quickly fired three shots at the police officers. Hare later told police he didn’t realize Hendricks was a police officer.

Langaard returned fire, hitting Hare.

In the aftermath, both Winje and Hare were taken to the hospital.

ADVERTISEMENT

Doctors, meanwhile, rushed to save Hendricks, but it was too late: He died on the ride to the hospital. The ambulance paused “outside the hospital receiving room, then drove directly to the Hennepin County morgue,” the Tribune reported.

“The only comment I have to make, you couldn’t print,” Minneapolis Police Chief E.I. Walling told reporters that night, his face flushed with anger, according to the Tribune.

Hare comes to Minneapolis

In the macho world of the blues, deals with the devil, casual violence and prison stints over men-and-women-done-wrong stories carried a certain cachet.

Had he never killed two people, however, Hare would still be a notable musical figure.

As a youngster in Arkansas, he learned some guitar, and he became proficient enough to begin playing with blues great Howlin’ Wolf (Chester Burnett) before Hare was 20 years old.

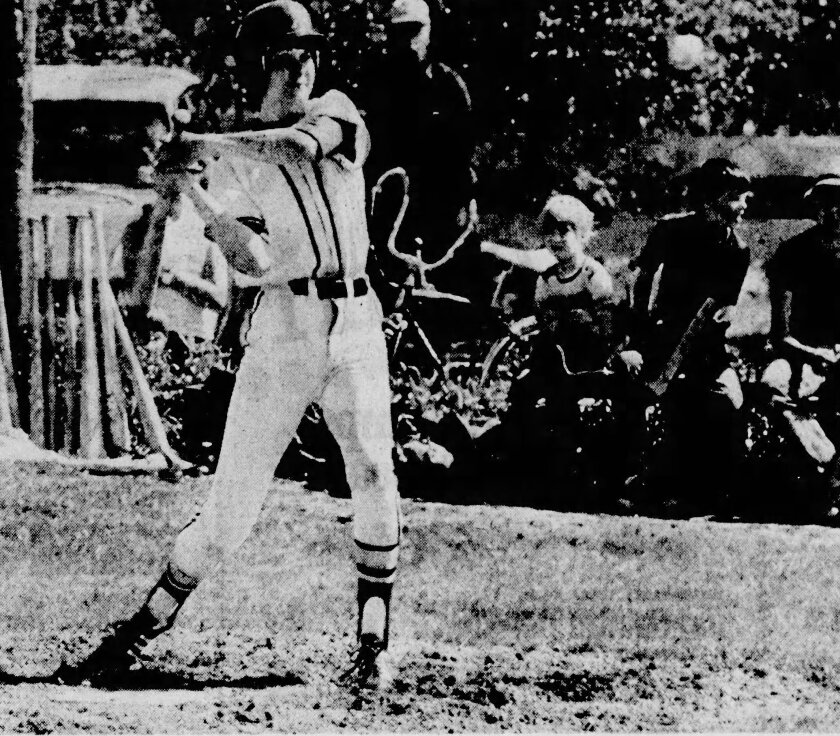

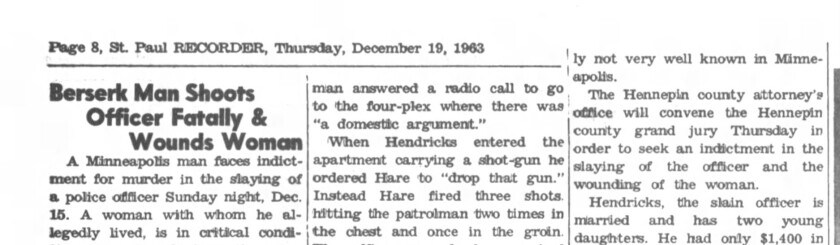

Harmonica player Marion "Little Walter" Jacobs, left, and guitarist Pat Hare are seen performing at Smitty's Corner in Chicago in this 1959 photo by Jacque Demêtre. Hare in 1963 would shoot and kill Minneapolis Police officer James E. Hendricks and Hare's partner, Agnes Winje. Photo by Jacque Demêtre

It was in Memphis where Hare made his name as a sideman on recordings by artists such as Rosco Gordon, James Cotton and others.

ADVERTISEMENT

Eventually, Hare graduated to the guitar chair in the Muddy Waters band — one of the most coveted assignments in the blues. Hare can be heard on legendary Waters recordings such as “Forty Days and Forty Nights” (1956) and “Got My Mojo Working” (1957), among many others on the Chess Records label.

Hare’s last recording with Muddy was one of the greatest: A seminal live recording called “Muddy Waters at Newport 1960.” It showcased Muddy and his crack ensemble at their best. Today, this album is considered an essential blues recording.

Soon after, Hare would be lured to Minneapolis by another Muddy Waters associate, harmonica player George “Mojo” Buford. Buford had persuaded several Chicago blues artists to move to Minneapolis, helping to create an authentic blues scene in the Twin Cities.

But Hare’s time in the spotlight — at least as a musician — would soon come to an abrupt end.

Evolution of a song

“I’m Gonna Murder My Baby” was not an original musical idea of Hare’s.

The song began life in the early 1940s as “Cheating and Lying Blues.” It was written by the singer and entertainer Doctor Clayton (Peter Joe Cleighton) and released as a 78 record in 1941.

In the few photos of Clayton that survive, he wears bold white, round glasses that highlight the knowing twinkle in his eyes. He was a professional musician, performing pop songs and blues alike, peppered with then-current references and slang. Tongue-in-cheek songs about relationship woes would certainly find receptive audiences in nightclubs and near jukeboxes.

Clayton’s “Cheating and Lying Blues” was a stop-time blues song, led by a walking piano style perfect for dancing. While the chorus is the same as sung by Hare, the verses are comical, and meant to elicit whoops and hollers:

‘Bout three or four nights ago

I had to work kinda late

Somebody broke out my back door

Like he was Superman’s mate

The song was covered by many blues artists, in many contexts, but its most famous iteration is as a song alternately called “Goin’ Down to Eli’s,” as performed by Robert Nighthawk (Robert Lee McCollum) and captured on the incendiary blues album “Live on Maxwell Street — 1964.”

Nighthawk's sharp, keening slide guitar cuts through the crowd. Unlike Hare’s version, which picks up the story at trial, Nighthawk memorably begins at Eli's pawnshop:

I went down to Eli’s

To get my pistol out of pawn

When I got back home

My woman had gone

“Goin’ Down to Eli’s” became the version that most blues artists would reference and perform over the years.

It wasn’t until 10 years later, in 1974, that Hare’s unissued version, plainly called “I’m Gonna Murder My Baby,” was finally released on a black-market album called “706 Blues: A Collection of Rare Memphis Blues.” Long talked about in blues circles, the song became a favorite of collectors for its rarity, its innovative sound, and the sad-but-true story of Pat Hare.

‘Good morning judge’

The killing of Officer James Hendricks shocked Minneapolis, still reeling from the assassination of President John F. Kennedy only three weeks earlier, on Nov. 22, 1963.

Hendricks had been on the police force for only four years. The police department started a fund for his family, wife Betty, and his two young children, Kathy, age 12, and Jill, 10.

“He was very devoted to those two little girls of his, and when we’d stop, they would come running out and have a kiss for him,” his friend and partner Caywood Johnson remembered in a Dec. 17, 1963, Minneapolis Morning Tribune story. “He really loved that.”

Hendricks was laid to rest on Dec. 18, 1963, at Fort Snelling National Cemetery.

Meanwhile, Agnes Winje was regaining consciousness and finally gave a statement to police. She said she saw Auburn Hare fire the shots that killed Hendricks, and corroborated much of the statement Hare had earlier given to police.

“She gave her side of the ‘nagging’ business,” said Calvin Hawkinson, inspector of detectives.

Though it seemed her condition had been improving, Winje died on Wednesday, Jan. 22, 1964, leading to a second murder charge against Hare.

But his trial, unlike his boastful murder ballad, was routine. There was no “Good morning judge, and your jury too.” No “I’m gonna murder my baby, don’t do nothing but cheat and lie.”

The fiction of his song ripped away, without a guitar or a gun, Hare was convicted of first-degree murder on Feb. 19, 1964, and sentenced to life in prison. Hare pleaded guilty to third-degree murder in Winje’s death, and received an additional 25 years on that count.

Aftermath and legacy

Pat Hare spent his remaining years in the Minnesota Correction Facility in Stillwater, where he started a band called Sounds Incarcerated.

After his conviction, he would adapt his earlier statements to police. In a 1973 letter from Hare, published in 1991 in the magazine Juke Blues, Hare would claim that the police shot him first, and that Winje was caught in the crossfire with police.

In a 1977 Star Tribune story about the prison band, Hare expressed his desire to be released and go back to music.

“That’s the only thing I do,” Hare said. “That's a must.”

Hare had one more turn in the spotlight for his musical talent, and not his criminal record. Hare was allowed — accompanied by a guard — to see his old bandleader, Muddy Waters, open for Eric Clapton in 1979 at the St. Paul Civic Center. Muddy invited Hare to the stage, and the two played together one last time.

“You got a lot of time to do, so you do it,” Hare said in a 1980 interview with the Twin Cities PBS show “Wyld Ryce.” “You don’t try to do it two or three days at a time, you do it one day at a time. Just one. It turns out much better.”

Just a few months after that program aired, Hare died of lung cancer on Sept. 26, 1980. He is buried in Fairview Cemetery in Stillwater, a quiet ending to a rowdy, distorted life.

Hare was inducted into the Minnesota Blues Hall of Fame in 2015, in the “Blues Legacy” category.

Meanwhile, Hendricks is remembered annually on his end-of-watch anniversary, Dec. 15, by the Minneapolis Police Department and other law enforcement agencies.

Sources: “Pat Hare: A Blues Guitarist” by Kevin Hahn, and Pat Hare discography : www.wirz.de ; Minneapolis Star Tribune/Morning Tribune via newspapers.com .