WALL, S.D. — Jim Boensch points out a number of switches and lights on a nearby electronic console. He gives a detailed rundown of what each does as well as gives a demonstration of an ear-piercing alarm. Everything seems to be operating just as it should.

He nods and then turns to the others in the room and prepares to proceed.

ADVERTISEMENT

“OK,” he says with a stark calmness. “Let’s jump into World War III.”

Thankfully, there is no danger of nuclear annihilation on the horizon. Boensch, a retired Air Force major, is in the underground Delta-1 Launch Control Facility at the Minuteman Missile National Historic Site just a short drive down Interstate 90 from Wall in western South Dakota.

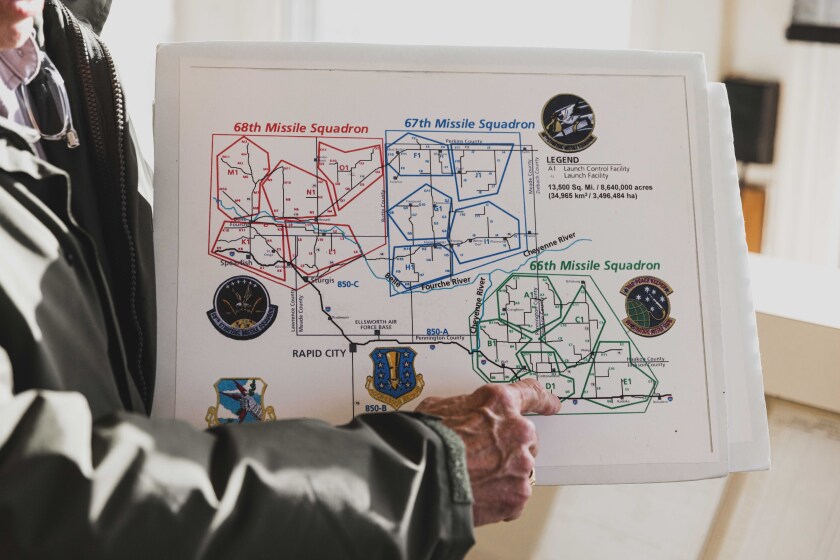

The equipment he is demonstrating is all era-accurate and authentic, though decommissioned, and was one of 15 such facilities in the state that once stood guard every second of every day in the event the president of the United States issued an order for a nuclear strike against a foreign enemy. With the late 1991 dissolution of the Soviet Union, the chief nuclear rival of the United States, the need for the Delta-1 site and its South Dakota sister facilities became less crucial, and with the exception of the one near Wall, all were decommissioned and destroyed.

“This is the last pair of this type in the world. There are no more,” Boensch told the Mitchell Republic during a tour of the grounds earlier this year, referring to the underground launch station and a deactivated missile silo just a few miles away. “They blew up the launch tubes and sold the land back. 149 of 150 missiles are gone.”

Once part of the 44th Strategic Missile Wing at Ellsworth Air Force Base, the site now serves as a museum, open to tours to the public and dedicated to the history of the Cold War and the role South Dakota and the Great Plains states played in the conflict. It is a chance to see the last remnants of the state’s nuclear Minuteman Missile fields.

In 1985, if South Dakota had been ranked apart from the United States based on the number of nuclear warheads located within its borders, the 150 warheads on the Minuteman Missiles would have ranked the state sixth in the world. That would place it right behind China with 243. It had more nuclear warheads than India, Pakistan, Israel, North Korea and South Africa combined.

ADVERTISEMENT

Cold War deterrent

When the United States dropped a pair of atomic bombs on Japan in 1945, it hastened the close of World War II. With Nazi Germany already defeated in Europe, the world breathed a sigh of relief as its armies, navies and air forces were recalled home and the conflict began to recede into the history books.

Though the United States and Soviet Union were allies and on the same victorious side during World War II, a division in military aims and ideology soon began to widen between the superpowers. By 1949, the Soviet Union developed its own nuclear technology, and a decades-long arms race kicked off, with both countries building large nuclear arsenals that threatened to destroy the other side.

Intercontinental ballistic nuclear missiles were part of those arsenals. Able to be launched at a moment’s notice and fly thousands of miles to deliver an atomic warhead payload on the enemy, the Minuteman Missiles were among the first developed by the United States as part of its “nuclear triad,” a series of nuclear warhead delivery methods that, along with the missiles, included missiles launched from submarines and bombs delivered by heavy bombers.

When the United States was looking for a place to establish those nuclear missile launch sites, they turned to a region in the Great Plains that included South Dakota, North Dakota, Wyoming and Montana.

“Most of them were in the middle part of the United States, up north. These missiles would go over the North Pole, and it shortened the distance to your targets without having to build bigger missiles that would be required if you put them down in Texas or Florida,” Boensch said.

The United States struck deals with local landowners, and by 1963 the first silos in South Dakota were active. Over their service life those silos housed the Minuteman I and II series of missiles, the second iteration of which could carry a 1.2 megaton warhead capable of delivering the equivalent devastation of 1.2 million tons of TNT with a range of 7,500 miles. That allowed it to strike virtually any target on Earth. Each one carried 66 times the power of the bomb dropped on Hiroshima, Japan, a bomb that killed 144,000 people. There were 150 such missiles within South Dakota’s borders.

Always at the ready, the missiles were never used and were removed from active status in 1991 before being completely removed later in the early 1990s. Congress established the Minuteman Missile National Historic Site in 1999, the legislation for which was passed after a bill to establish the site was introduced in 1998 by Senators Tom Daschle and Tim Johnson.

ADVERTISEMENT

Hiding in plain sight

Though now more than a quarter century removed from service, the Delta-01 launch facility, and its nearby companion historic site, the Delta-9 Missile Silo, appears much as it did when it was active.

During its service, access to the facility was strictly controlled, but the existence of the missiles and even their locations were not top secret. Local residents were aware of the nature of their neighbors, and even the Soviet Union were keen as to where they were located.

That was by design, said Boensch, who works as an education technician at the Minuteman Missile National Historic Site.

“We were a deterrent force. To have a good deterrent, you have to have a really great weapon, so from the other side they know you’ve got it and they know you can use it,” Boensch said. “It was no secret. All you had to do was follow the power line out to the middle of nowhere and you had a missile.”

The launch facility appears as a relatively small, unremarkable low-slung building surrounded by a chain link fence and gate. A basketball hoop stands just inside the fencing. Entering the building takes one into a receiving area, where missile crews, which were swapped out after every 24 hour shift, would be vetted and checked in.

Through one door in that area, toward the back of the building, is a living area that housed facility personnel, including security. Preserved much as it was during its most recent active period, it features a lounge area with a television, a small dining area, kitchen and sleeping quarters for those on-site.

Space is limited, the accommodations simple but comfortable. For the most part, it does not resemble a military facility.

ADVERTISEMENT

It is through a second door in the receiving area that the perception changes. There, an elevator with highly controlled access leads to the underground bunker that housed the actual launch controls for the missiles at their command. A brief elevator ride descends approximately 30 feet to reveal a dark, concrete bunker area.

A few meters ahead, a 16,000 pound blast door that sealed the missileers from the outside world is propped open. In a display of tongue-in-cheek humor, a mock Domino’s Pizza box has been painted on the front with the slogan “Worldwide delivery in 30 minutes or less or your next one is free.”

Squeezing past the blast door brings visitors into a brightly-lit room full of vintage equipment that was crucial to launch operations. Low frequency and satellite communication systems line the walls, and a pair of chairs bolted to slide rails gave personnel a station from which to tend to it all while remaining strapped in securely. Simple sleeping bunks with a curtain grace the opposite wall.

Staff in the bunker drilled regularly for a number of different scenarios, including launches. But even with constant training, there was a lot of downtime below ground. Boensch said many missileers would spend their time reading textbooks, preparing for exams.

“We read. About half of us got our master’s degree. It was a great place to study. And I had two little girls back at the base. I wanted to play with them when I got off duty (and not study),” Boensch said.

Leadup to launch

Studying aside, they were also prepared in the event of a nuclear emergency.

There is no one button to launch the missiles. Once a confirmed launch order was received, each missileer turned a key from their stations, which were about 12 feet apart. Each key had to be turned within two seconds of each other, which prevented any one person from initiating a launch without the other.

ADVERTISEMENT

On one wall is a small red metal lock box with two combination padlocks. Like the two-person key launch system, the padlocks are another safeguard against any single person going rogue and attempting an unauthorized launch on their own. Both people had to be in agreement to open the box.

“Why in the world would you need a safe up here inside this bank vault? With two locks on it, you did not know the combination of your partner’s locks. You were the only person in the world that knew your opening combination. Trust was a very hard thing to come by when you’re dealing with nuclear weapons. You’ve got to be absolutely sure,” Boensch said.

The box contained materials for authenticating communications to make sure any such launch order received was authorized by the president of the United States or their successor. The content of those authenticators is still classified to this day. The actual launch keys were also inside the box.

Things begin to move quickly once the lock box is opened.

“We lay our keys down on this cabinet. We pick the right one. We do this independently of the other person,” Boensch said. “We go through whatever procedures we do to authenticate the message. Once we agree it is a valid and authentic message, we’re going to war. Nuclear war. And we don’t have a lot of time to do this.”

The hours of practice and drills kick in. The pair are now almost on autopilot, having ceaselessly trained for this exact moment. Each missileer inserts their launch key into the receptacle at their station. They strap their seatbelts on.

At the end of the countdown sequence, both turn their keys. At that point, missile silos like the Delta-9 site preserved a few miles down the road, move into action. The door at the top of the silo is flung off, revealing the weapon underneath.

ADVERTISEMENT

“An explosive squib fires, dragging that whole thing into a recess in that 12-foot diameter launch tube, getting it out of the way of the missile. About the same time, two Howitzer shell-like gas generators drive a piston tied to a pulley down, rolling that massive 180,000-pound door sideways to the south, rolling on 18-inch steel wheels,” Boensch said. “It clears that tube in less than three seconds.”

Moments after the launch order is received, a Minuteman Missile is airborne and bound for its target. World War III has begun.

Reflection

Boensch and his fellow Air Force colleagues never had to take those fateful steps to actually launch a nuclear missile. Cool heads and world-saving diplomacy eventually won the day, and with the collapse of the Soviet Union, a nuclear deterrent on the Cold War scale was no longer needed.

The missile fields in South Dakota were decommissioned and destroyed, with the exception of the facilities at which Boensch and his colleagues give tours to the public. Modern land-based missile facilities are still a part of the United States’ defense forces, with locations still maintained in North Dakota, Montana and Wyoming.

The Cold War may be over, but the need for a nuclear deterrent remains, Boensch said. Geopolitical winds can shift, and leadership changes at the national level can alter defense priorities. Regardless of election results, the safety of America remains paramount, Boensch said. In addition to the current modern land-based missile silos and submarine-based nuclear weapons, the Air Force is expected to purchase 100 new B-21 Raider bombers, the first of which will be hosted at Ellsworth Air Force Base.

The new bomber, which will complement the current fleet of B1 and B2 bombers, represents a generational leap as a dual nuclear and conventionally capable, stealth, penetrating, long-range strike platform, according to a release from the Air Force.

“I think regardless of what political party is in charge, I think everybody realizes it’s a necessity,” Boensch said.

Once a domain strictly off-limits to the general public, the Minuteman Missile National Historic Site now welcomes them with open arms to share the story of the sentinels on the prairie that assured America’s enemies any attack would be met by an equal, if not greater, force in return.

Nearly 100,000 people visited the site in 2020. Some of those are fellow veterans that Boensch gets to interact with, sharing his stories and listening to theirs.

It also offers him a chance to reflect on his own service and the service of his fellow missileers, most of which were no older than their mid-20s when they were stationed here. The technology and procedures are indeed fascinating, but in the end, the life or death actions came at the hand of missileers with a pair of small brass keys.

There was no glory in the role, just a call to serve their country and to be at the forefront of protecting it should it come under attack.

“I had to do some heavy thinking on what I really valued in life, what I really considered important. And I think service is the real reason why we’re here. I really do,” Boensch said. “But it’s just so rewarding to shake the hands of these people. And the folks who never served, too.”

The Minuteman Missile National Historic Site is open to tours to the public. More information on the facilities and tours can be found at www.nps.gov/mimi/index.htm or by calling 605-433-5552.