Editor’s note: This is Part 2 in a Forum News Service investigative series related to the disappearance of Belinda Van Lith, including an exclusive interview with the main suspect in her case. To see everything published in the investigation, visit the Van Lith investigation page .

MONTICELLO, Minn. — A young woman’s escape from a ‘69 Chrysler Newport on a cold Minnesota evening in December 1974 forever changed the course of Belinda Van Lith’s missing person investigation.

ADVERTISEMENT

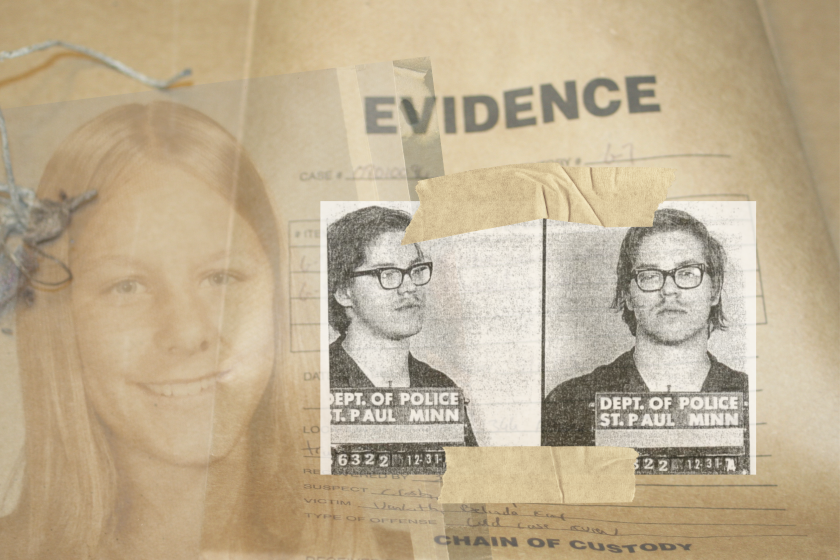

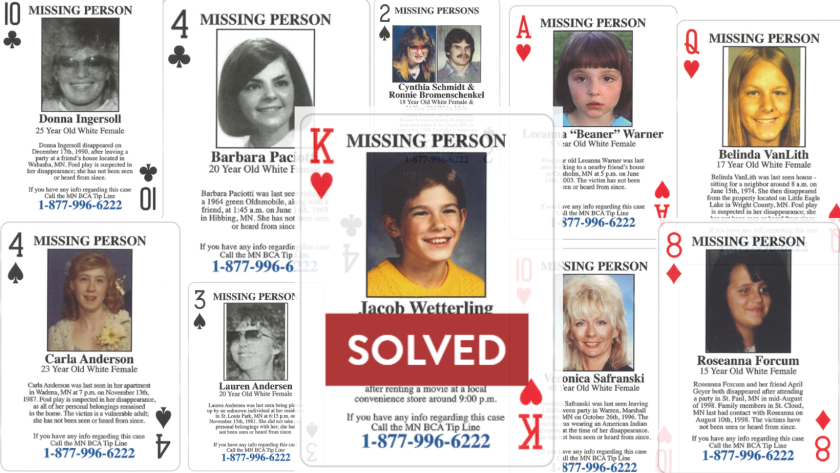

Belinda had vanished just a few months before on June 15, 1974, while the 17-year-old was house-sitting a residence on Eagle Lake, near Monticello. Timothy Crosby, who was staying alone in his parents’ cabin 100 yards away, was the last known person to see her.

Six months after Belinda went missing, Timothy Crosby, the last known person to see her was arrested for abducting a young woman in St. Paul and taking her to his family's cabin on Eagle Lake, where he repeatedly sexually assaulted her.

The victim escaped to tell investigators her story — and provide insight into the mind and capabilities of Timothy Crosby.

What did investigators do when they discovered the last person to see Belinda carried out such a henious attack at the very location where Belinda was last seen? Listen to find out.

This episode is written, narrated and produced by Trisha Taurinskas. The Vault's editor is Jeremy Fugleberg. To read the full story, with images related to the case file, go here: https://www.inforum.com/news/the-vault/he-was-the-last-to-see-belinda-van-lith-alive-when-he-later-attacked-a-woman-he-finally-became-a-suspect

Investigators didn’t initially consider Crosby a suspect. He was the 18-year-old son of a St. Paul police officer. He was quiet, with no known criminal record.

That all changed when the Wright County Sheriff’s Office received a phone call on Dec. 31, 1974, regarding a sexual assault that took place at a familiar cabin the previous day.

Crosby had kidnapped a 19-year-old young woman near the University of Minnesota. He pointed a gun to her head as he forced her into handcuffs, blindfolded her and took her to his cabin on Eagle Lake. He tied her up and sexually assaulted her. Then, he drove her to a nearby park and threatened to kill her.

Yet, she escaped — and the information she provided to law enforcement caused Wright County Sheriff’s Office investigators to consider Crosby as a potential suspect in Belinda’s disappearance.

A months-long Forum News Service investigation, in collaboration with the Van Lith family, led to the recent release of Belinda’s 1,200-page police case file and an exclusive interview with Crosby.

The investigation reveals glaring failures in the early stages of Belinda’s case, including many missed opportunities to fully investigate Crosby’s possible involvement in her disappearance.

ADVERTISEMENT

Many suspicious signs were downplayed or ignored. Law enforcement did not attempt to search the field where Crosby’s vehicle was stranded the night Belinda went missing. They did not examine evidence stemming from Crosby’s December 1974 crimes that could have, potentially, put Belinda’s case to rest.

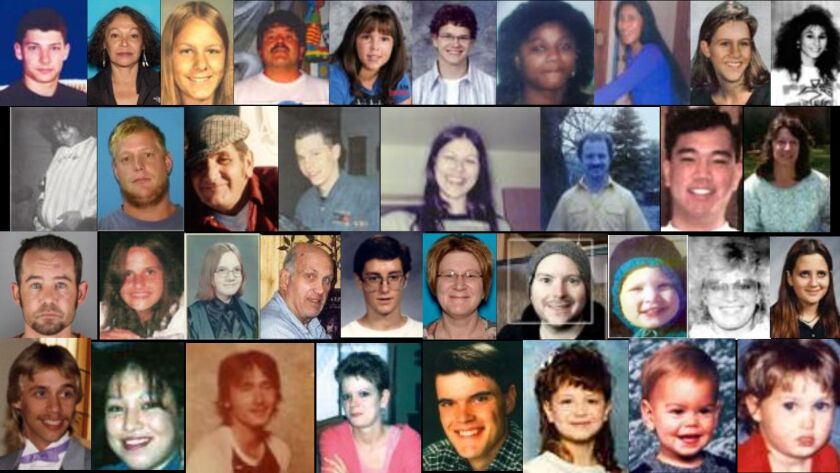

Meanwhile, Belinda’s case file shows, Crosby earned a record over the next decade as a serial criminal, kidnapping and assaulting multiple women. Yet he faced only light punishment, or charges against him were dropped.

The Wright County Sheriff’s Office Investigations Division attempted from 2009 to 2013 to fill the gaps left behind from the initial investigation, yet their efforts did not lead to justice for Belinda or her family.

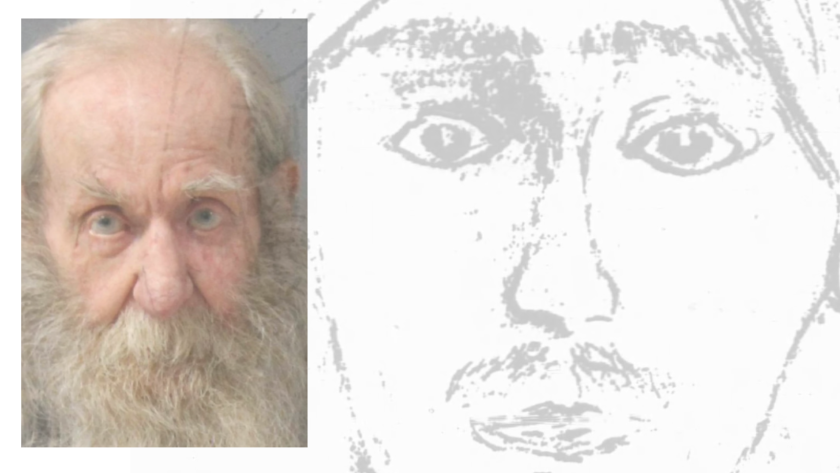

In 2010, the state of Minnesota successfully argued that Crosby was a sexual recidivist and a danger to the public. As a result, he was committed to the secure Moose Lake Sex Offender Program facility, where he is currently locked up. He has not been charged with crimes related to Belinda’s disappearance.

Crosby is named as the sole suspect in the investigative file. In an interview with Forum News Service, he denied having anything to do with Belinda’s disappearance.

The Wright County Sheriff’s Office has declined opportunities to answer questions presented by Forum News Service related to this case.

The case that opened their eyes

The laundry list of items discovered by investigators in Crosby’s vehicle in the early morning hours of Dec. 31, 1974, showed he was prepared for the kidnapping and sexual assault of his victim — and that he was violent.

ADVERTISEMENT

The young woman was hitchhiking near the University of Minnesota when Crosby offered to give her a ride on Dec. 30, 1974. She accepted, yet very quickly realized she was in danger.

She tried to leave through the passenger’s side, but she couldn’t — the door wouldn’t open.

“I turned around and he had a gun pointed at my side and he had handcuffs in the other hand and he told me to put my hands behind my back,” the victim told investigators in a Dec. 31, 1974, interview, after she escaped. “And then he pushed me back and headed out on the freeway and the direction he went was towards St. Cloud.”

Crosby kept his gun out during the one-hour drive to his family cabin on Eagle Lake. He threatened to shoot her if he made her nervous. When they arrived at the cabin, he sexually assaulted her at knifepoint. He poured rubbing alcohol on tissue paper and used it to cover her mouth. He handcuffed her and took photos of her with his Polaroid camera.

Then he took her back to his car and drove to Montissippi Park in nearby Monticello. Women’s clothing and underwear had been found in that very park four months earlier, in August 1974.

Crosby eventually began driving back toward the University of Minnesota that evening. He told her he’d drop her off where she had initially requested. Yet, he didn’t.

The victim saw a cop car and maneuvered her foot onto the gas pedal. The cop followed. She began aggressively honking the horn in an attempt to alert police that she was in trouble.

ADVERTISEMENT

Eventually, Crosby lost control of the car and crashed into the boulevard.

“I knew he was going to kill me because I knew he wasn’t going to let me go,” the victim later told law enforcement.

Inside Crosby’s car, officers discovered a revolver, a long-blade hunting knife, a butcher knife, masking tape, ammonia inhalants, rope and handcuffs. Crosby also had a Polaroid camera and film, which he had used to take photos of his victim while she was restrained at his Eagle Lake cabin.

The photos he took of the victim were found strewn about the floor of the car.

A roll of photos was taken and developed by investigators, but “the film showed no recognizable pictures,” according to the police report.

They, too, noticed Crosby’s passenger’s side door was incredibly difficult to open.

“Part of the door latch is missing and while the door can be opened from the inside, it is quite difficult to do so, requiring both hands to do so,” the report states.

ADVERTISEMENT

All of this information lined up with what the victim told officers: She was unable to initially get out of the passenger door, and that Crosby was prepared.

Inside Crosby’s vehicle, investigators also found an array of women’s clothing, including a yellow halter top, a navy blue shirt with an embroidered frog, women’s underwear and a pink bra that had been cut.

The victim told investigators he forced her to wear women’s clothing while he assaulted and photographed her. Crosby told investigators that the clothing belonged to his sister, yet there were no documented efforts to prove that to be true.

The search warrant

The Wright County Sheriff’s Office, in coordination with the St. Paul Police Department where Crosby’s father worked as a police officer, executed a search warrant on the family’s St. Paul home.

They documented just one item: Crosby’s diary, which began roughly two weeks after Belinda went missing. The diary was returned to Crosby, with no documentation of its contents.

In a letter penned by Crosby on July 11, 1975, he thanked then-Wright County Sheriff Darell Wolff for the swift return of his diary.

“I would like to give you my personal thanks for helping me to receive my diary so quickly from your county,” he wrote.

ADVERTISEMENT

Investigators would learn in 2009 that there could have been other items of interest discovered during that search.

Jim Powers, who worked for the Wright County Sheriff’s Office in 1975, remembers a few other items that weren’t documented: two locked metal case files, and a photocopied list of 50 ways to dispose of a body. One of the items on the list, he recalled, was putting the body in manure.

The Crosby cabin was not subject to a search warrant at that time.

Missed opportunities

It wasn’t clear what Belinda was wearing when she went missing. Investigators didn’t ask Crosby, the last known person to see her, when they knocked on his door days after she vanished.

Her family didn’t know, either.

Belinda’s siblings — and friends — were not shown the clothing Crosby forced his victim to wear. They weren’t shown the clothing found in the park and his vehicle, either.

They didn’t know, at all, about the clothing obtained by law enforcement until they received the investigative file in the summer of 2023.

Now, they’re wondering if they still have a chance.

Forum News Service has filed a records request with the Wright County Sheriff’s Office for information related to the physical evidence list in Belinda’s case. At the time of publication, that request has not been filled, or denied.

The request was made to determine if clothing discovered in Crosby’s vehicle was returned to his father.

In March of 1977, Crosby’s family lawyer requested that the Wright County Sheriff’s Office return the handcuffs, revolver and clothing taken as evidence. The attorney stated the items belonged to Glen, Crosby’s dad.

Correspondence included in the investigative file between then-County Attorney Wyman Nelson and Wright County’s Sheriff Jim Powers on April 8, 1977, indicates Glen might have gotten what he wanted.

“Do you have any objections? The case they were involved in were disposed of,” Nelson typed in the message, referring to Glen’s request. “The father will probably prevail. Let me know.”

Below that printed statement is a handwritten note, addressed to Powers.

“We have no basis to hold these items,” it states.

The field

In the days following the December 1974 kidnapping and sexual assault, Wright County sheriff’s officers went back to the drawing board in Belinda’s case and began asking Crosby’s Eagle Lake neighbors some questions.

Residents of at least two cabins told investigators they remembered Crosby was staying alone on Eagle Lake the weekend Belinda vanished. They also recalled that, on the day she went missing, Crosby had gotten his ‘69 Chrysler Newport stuck in a nearby farm field, which left it covered in manure.

After numerous interviews, officers nailed down the details and timeline of the incident: Crosby had gotten his vehicle stuck in the field during the evening hours of June 15, 1974, and returned back to his cabin in the early hours of June 16.

That’s when neighbors saw Crosby hosing off his car.

Former Wright County Sheriff’s Office Detective Robert Kammer told investigators during a 2009 interview that the farmer who owned the land where Crosby was stuck came forward a couple months after the incident.

Crosby told the land owner on the evening of June 15 that he and his girlfriend were “parking” when his vehicle became stuck, yet there was no one else in the car when the farmer arrived to help.

The check Crosby handed over to the farmer for his services had bounced, and he wanted Crosby to be held accountable.

Crosby had a different explanation, though.

In 1975, Crosby told investigators he had been drinking at a local bar and veered off the road on his way home, causing his car to crash into the manure.

Despite this information, the 1975 investigation into Belinda’s disappearance did not include a search of that field. (That wouldn’t happen until three decades later, which will be further explored in a future part of this series.)

Belinda’s siblings were never given any information related to the crimes Crosby committed in December of 1974 at the last known location where their sister had been seen.

They were not told that Crosby was the last known person to see Belinda — and they certainly were not aware that Crosby had been stuck in a nearby farm field the evening Belinda went missing.

A case gone cold

Crosby was charged with aggravated kidnapping with a dangerous firearm, robbery and sexual assault for his December 1974 crimes.

His legal team cut a deal — he pleaded guilty to aggravated kidnapping while possessing a firearm, a term that carries a minimum of three years in prison. Instead, he was then sent to St. Peter Hospital’s Intensive Treatment Program for Sexual Aggressiveness.

With Crosby behind bars, Belinda’s case seemed to go cold. Crosby, meanwhile, was granted parole in 1982 and released from St. Peter Hospital.

In the years after he was released, two more female victims escaped from Crosby. One woman escaped his vehicle after being held at knifepoint. The other threw herself out of his apartment window after being held captive for 16 hours.

Each woman lived to tell their story. What they told investigators in Belinda’s case exposed Crosby and provided clues to his potential involvement in Belinda's disappearance.

Editor’s note: This is Part 2 in a Forum News Service investigative series related to the disappearance of Belinda Van Lith, including an exclusive interview with the main suspect in her case. To see everything published in the investigation, visit the Van Lith investigation page . To listen to the corresponding podcast series related to this story, check out Forum Communications’ The Vault Podcast wherever you listen to podcasts.