ST. PAUL — The two sisters were in bed but still awake that night in April when one of them heard a noise. It sounded like someone was breaking into their parents' Selby Avenue home in St. Paul.

Katherine Irene McQuillan quickly grabbed the diamond rings worn by her sleeping sister, Alice McQuillan Dunn, thinking the possible intruder might be after them. And suddenly there he was, a man in the doorway. He was wearing a dark suit, a cap pulled low over a white mask across his face. He was wielding a .44 Colt revolver.

ADVERTISEMENT

It happened so fast. Katherine tried to scream, but the man flashed a light in her face, harshly illuminating the sisters in bed. The masked man said a few words to Katherine, something like "Be calm, I'm only here to do a little shooting."

He then hit Alice over the head with the pistol, then stepped back and aimed. He shot her sister, once, twice, then a third time.

He left, seemingly not even interested in Katherine, the diamond rings or the expensive silver dining service downstairs, only taking a check made out for $10.15 and 13 cents in coins from a downstairs room, before fleeing in a getaway car.

It was early April 26, 1917. The murder of Dunn, the daughter of the prominent owner of a plumbing business (which still exists ), shocked the city and the nation as the news rippled across the country.

A meticulous police investigation would quickly reveal a criminal plot that scandalized readers and quickly became one of Minnesota's most notorious murder cases.

Dunn's estranged husband, Frank Dunn, would be charged and convicted of her murder after it was found he had hired hitmen to do the dirty deed in his stead.

From bitterness to hatred

On paper, the Aug. 4, 1914, marriage seemed to be a good match. Frank P. Dunn was a prominent contractor in St. Paul, and Alice McQuillan was the daughter of a wealthy business owner. Yet from the beginning, the marriage seemed cursed.

ADVERTISEMENT

The couple immediately didn't get along, including a honeymoon trip to Duluth that seemed to have gone wrong, and before long, just 70 days after their marriage, Alice and Frank were separated. Frank seemed to have a temper and was very resentful that the marriage wasn't working, and blamed Alice.

When she filed separation papers in June 1915 that required Frank to pay her a monthly allowance and then moved to work as a stenographer out West, Frank's bitterness deepened into hatred. He was Catholic, and he believed divorce wasn't an option or perhaps that his wife would never grant it. So instead he started to consider other solutions, namely murder.

For Minneapolis police, Frank P. Dunn was an immediate person of interest in the murder of his wife. Yet he didn't fit the physical description of the murderer provided by eyewitness Katherine McQuillan. He also seemed to have a solid alibi, having stayed late at the Knights of Columbus club the previous evening, then returning home (his neighbors swore they heard him).

But police weren't convinced, so they locked him up anyway. For the moment, anyway.

The investigation provided a wealth of clues, and troubling elements of the murder that pointed to planning and forethought of a murder, not burglary. The telephone lines to the McQuillan home had been cut, hampering the family's chance to call police after Alice's murder.

The murderer had been completely uninterested in any valuables, had first stepped into a nearby bedroom that had once belonged to Alice before moving to the room where she was in bed, and had escaped in a getaway vehicle, presumably with an accomplice.

The 'tips'

On April 24, just days before the Dunn murder, Patrolman George H. Connery disappeared after arresting two men at a speed trap.

ADVERTISEMENT

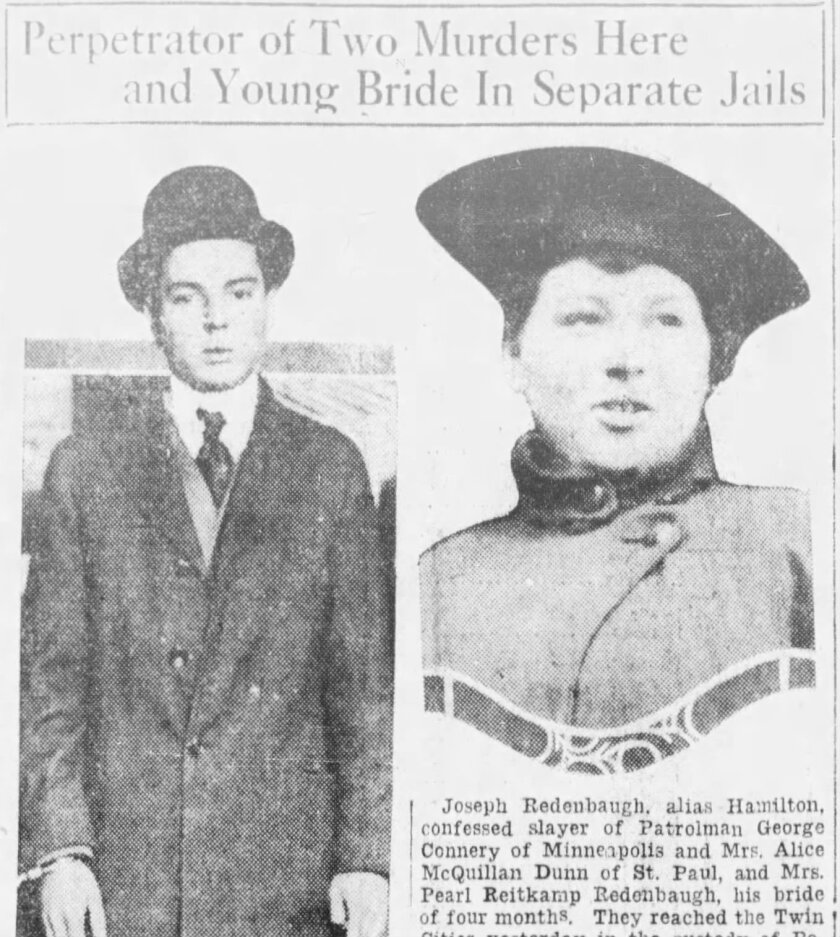

The two men had been stopped by police before, and Police Chief John O'Connor connected a few dots (likely via his numerous connections to the criminal underworld in Minneapolis and St. Paul) and discovered that one of the two was a small, tough criminal named Joseph P. Redenbaugh.

Connery's beaten body was found on May 6 thanks to a tip. He had been shot with a .44, the same caliber used in the Dunn slaying. And tire tracks at the scene matched those of a vehicle abandoned in St. Paul not long after the Dunn murder.

Were the two murders linked?

O'Connor also "gained" a few other tips that proved instrumental in cracking both the Connery and Dunn cases. He was tipped off that police should track down a man named Frank McCool, who had recently been detained as a robbery suspect in Nebraska. As it turned out, McCool was carrying a revolver — one with a serial number that matched the service weapon of Connery.

McCool broke down in a police interview and admitted he had been involved in the Dunn murder, but swore he only drove the getaway car. Redenbaugh was the trigger man, he said.

O'Conner was also "tipped off" that Frank Dunn had met with potential hitmen in Montana in 1915. Brought in to be interviewed by Minneapolis police, they said they had traveled to St. Paul and Dunn had discussed specific plans about how they could kill his wife.

Police detained Redenbaugh, who held out for a while before coming clean about his role in both murders. Redenbaugh said a St. Paul bartender named Mike Moore offered him $2,000 to kill Alice McQuillan Dunn, and he admitted to the murder of Connery, for which he was sentenced to life in prison.

ADVERTISEMENT

Dunn on trial

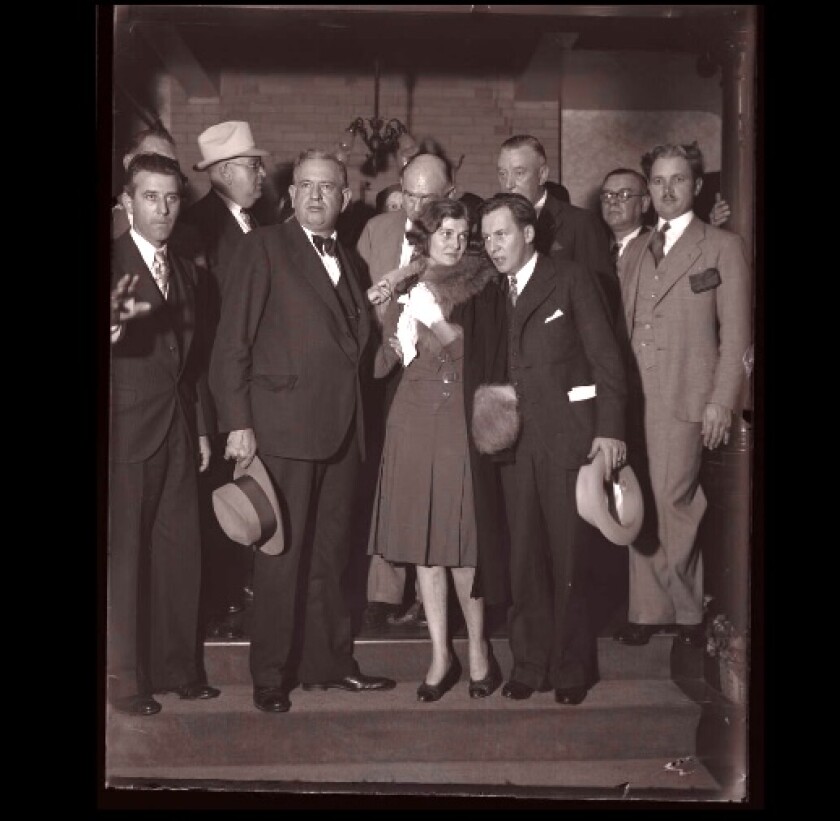

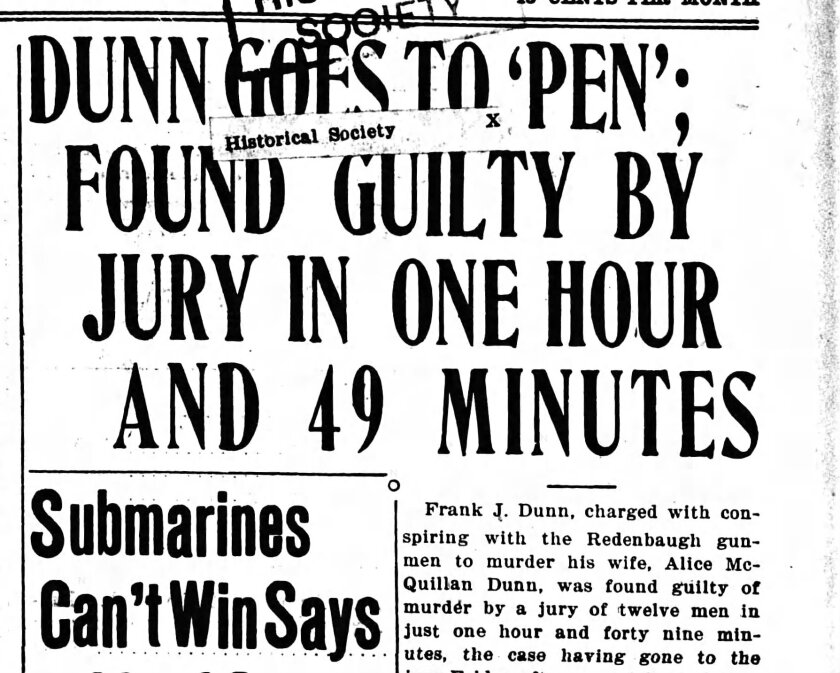

The trial of Frank Dunn started on June 14, 1917. The advance work by police made the sensational 15-day trial an easy decision for the jury, which promptly found him guilty of the premeditated murder of Alice McQuillan Dunn.

Redenbaugh testified as a co-conspirator, as did McCool. Dunn not only had worked through intermediaries to employ the two as hitmen, but he also had withdrawn funds from a safe deposit box after the murder to give to the men, who had promptly fled the city.

Dunn was sentenced to life in prison. The Minnesota Supreme Court rejected his appeal. He died in prison on Feb. 26, 1958.

The research for this article comes from "The Dunn-Connery Murder Mystery" published by J.M. Near in 1917; "Murder in Minnesota" by Walter N. Trennery (1985); and contemporaneous newspaper accounts, including from the Duluth News Tribune, the Bemidji Pioneer, the Minneapolis Journal and the Star Tribune.