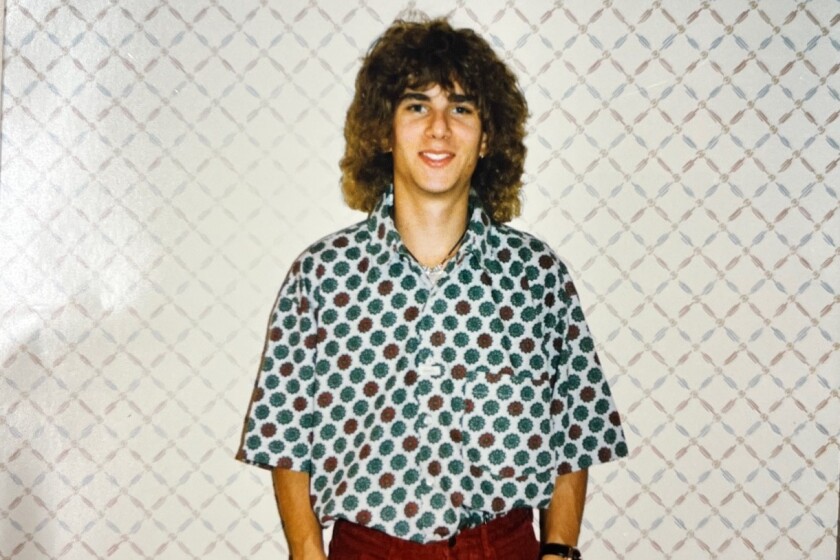

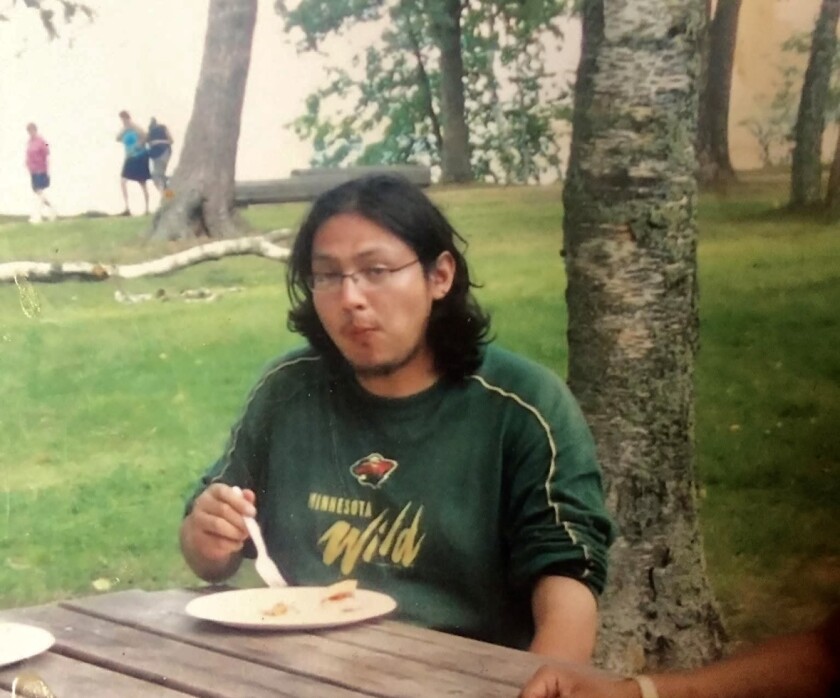

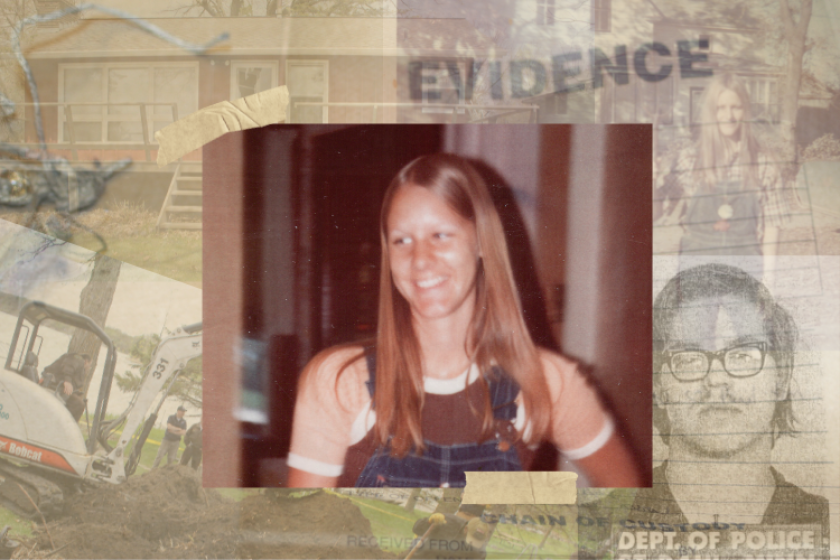

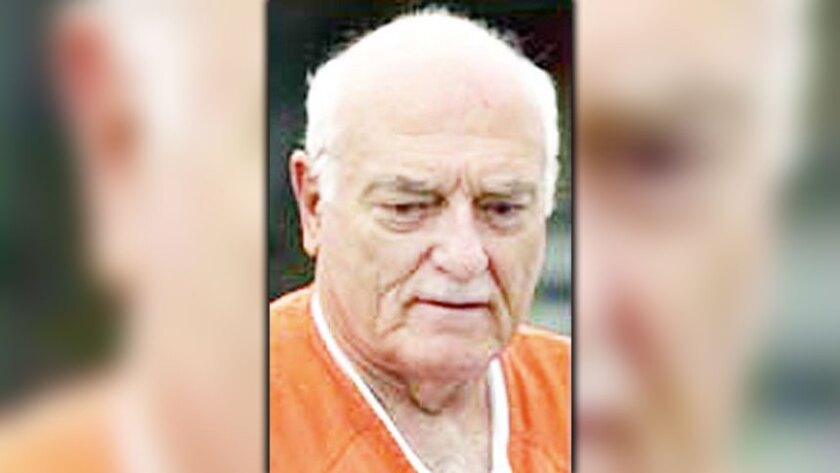

JACOBSON, Minn. — Just five days after his 18th birthday, James “Jamie” Tennison, of Grand Rapids, entered the Savannah State Forest, never to be seen or heard from again.

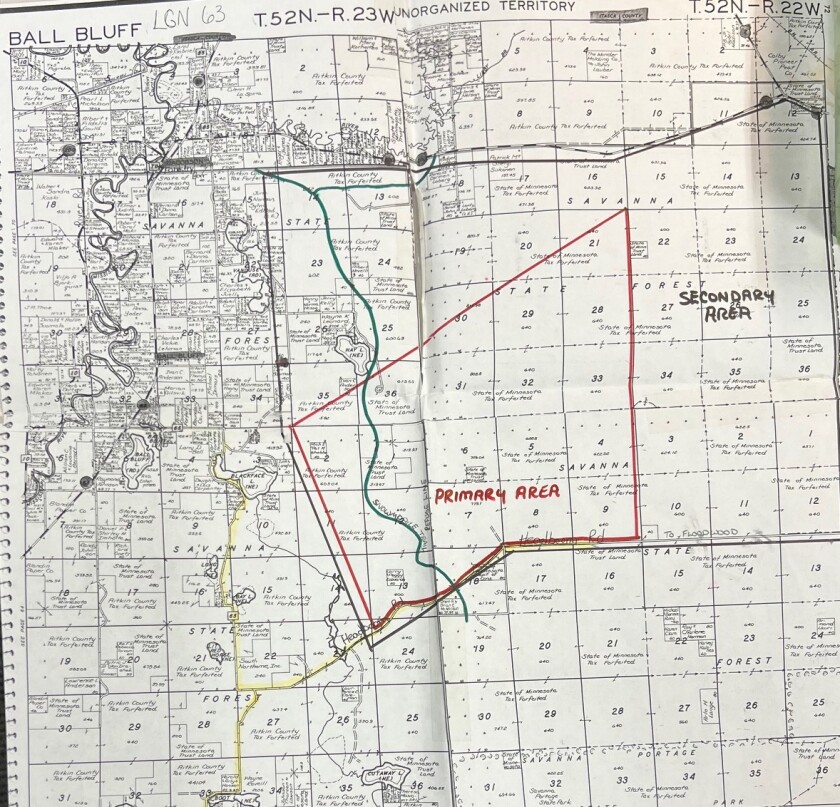

It was a warm, overcast afternoon Oct. 15, 1992, when Jamie and his father, James “Jim” Tennison, and friend, Jeff Wohlrabe, set out to hunt grouse.

ADVERTISEMENT

“I grew up in the Jacobson area and went to high school at McGregor, so that was a familiar area,” Jim said. “We were both fairly familiar with that area that we were hunting, which was about 3 miles south and 6 miles in on the Hedbom Forest Road.”

Furthering Jamie’s confidence in the woods was the training he received during a three-day survival course and Minnesota Deer Hunters Association Forkhorn Camp, and he frequently camped in the woods alone, Jim said.

“He was supposed to be meeting up with a girl in Grand Rapids to go out that evening,” Jim recalled. “He reminded me of that, and we parted ways.”

The hunting party agreed to meet back at the truck at 4 p.m. before Jim and his friend headed south on the reserve line while Jamie went north.

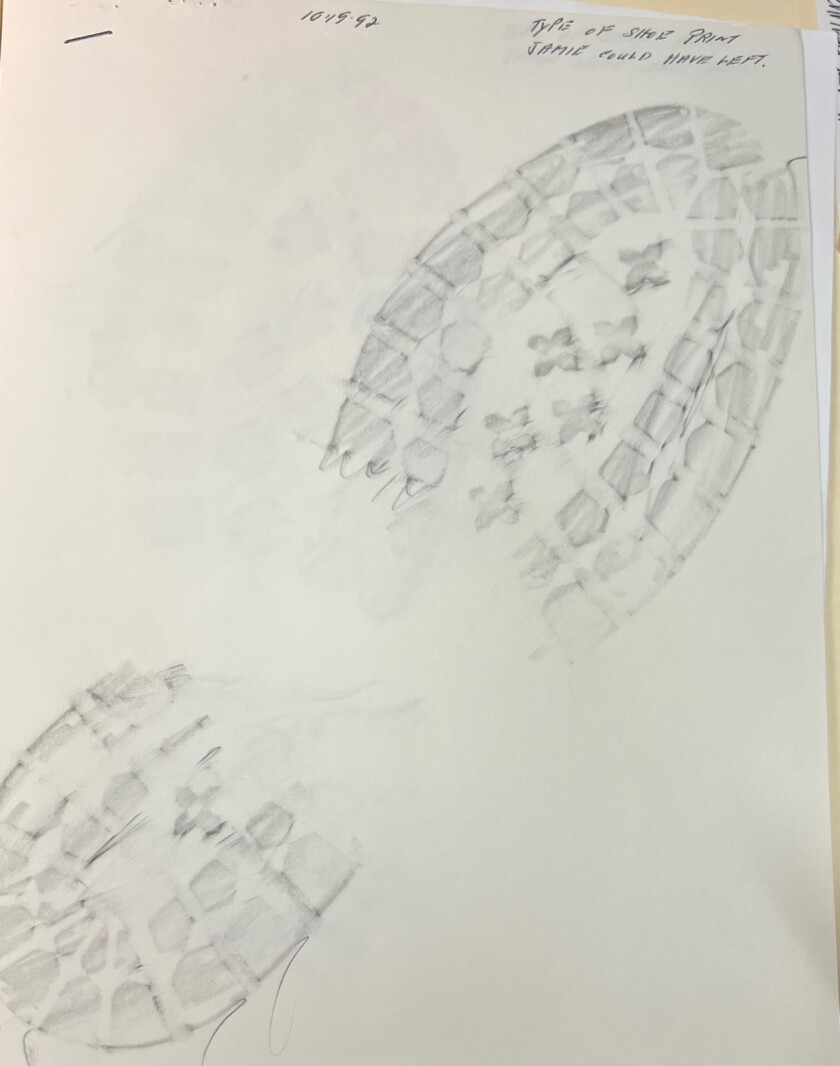

Dressed in ripstop camouflage pants, a lightweight green camouflage jacket with a vest, a red-and-blue flannel shirt and a Los Angeles Kings ball cap, Jamie walked alone with his brand-new Remington 870 Express 12-gauge shotgun in hand.

A billfold containing money and Jamie’s ID and a new pistol his father had given him for his birthday were left behind at the family hunting shack, Jim said.

When 4 p.m. rolled around, Jamie didn’t show. The temperature dropped, and by 6 p.m., cold rain turned into wind and snow. A large fire was built. Shouts and shots were fired, but no reply.

ADVERTISEMENT

Jim would later discover Jamie’s compass was still lying in the ammo box back at the shack.

“We did hear some shots, so he probably shot some grouse. He got off the trail, off the road, and he got confused,” Jim presumed. “Without a compass in the woods on a cloudy day, you could get really disorientated as far as sense of direction, and I think that he was lost.”

Excursions into the woods showed no sign of Jamie, and the sheriff’s office was notified at around 10:45 p.m.

”I think he looked around, and he found someplace he could hunker down and get as much shelter as he could," Jim suggested, "whether it be an upturned tree or something like that. He dug himself in, and he covered himself up with leaves, and he went to sleep and never woke up.”

According to a deputy’s report on file at the Aitkin County Sheriff’s Office, the responding officer stated: “I went out to where they last saw him, sat near that area with my siren going at intervals of 15-20 minutes, at which time, I would shut it off and listen. I did this for approximately 1 1/2 hours.”

Meanwhile, Jim and Wohlrabe stoked the fire 1 mile away, yet reportedly could not hear the siren due to the heavy snowfall.

“Aitkin County basically did not run any kind of search and rescue,” Jim claimed. “They never set foot in the woods at all, didn't do any organizing. It was all done by friends of mine, or volunteers or Minnesota Power.”

ADVERTISEMENT

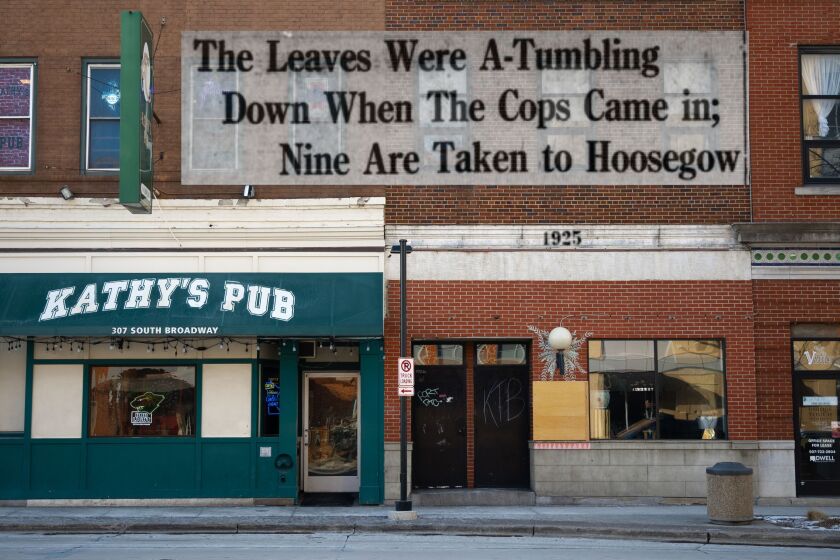

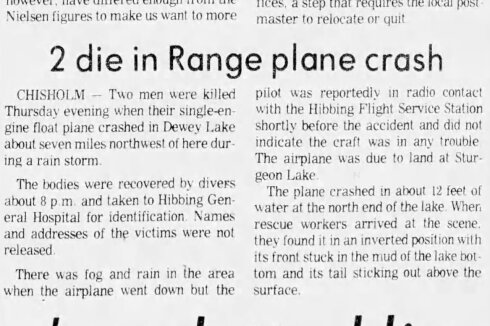

The sheriff’s office called off its search for Jamie on the morning of Oct. 20, 1992, according to an article in the Aitkin Independent Age newspaper.

Over the next 10 days, the Tennison family, friends and co-workers conducted extensive searches in the thick, swampy brush and timber-filled woods with floating bogs and numerous predators. Volunteers used dogs, horses and helicopters to comb the area in a grid-style search, Jim said.

“People that suffer from hypothermia, what they do is they run, they start shedding items,” Jim said. “Caps, vests, guns, whatever. We never found anything. So wherever Jamie ended up, all his stuff ended up with him.”

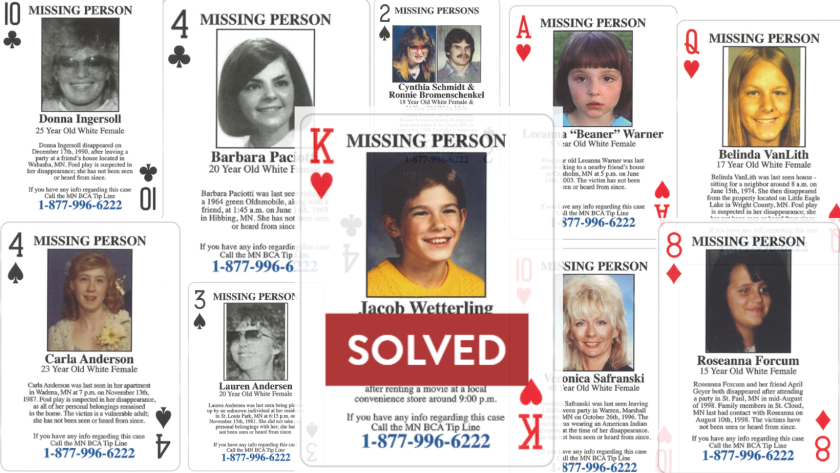

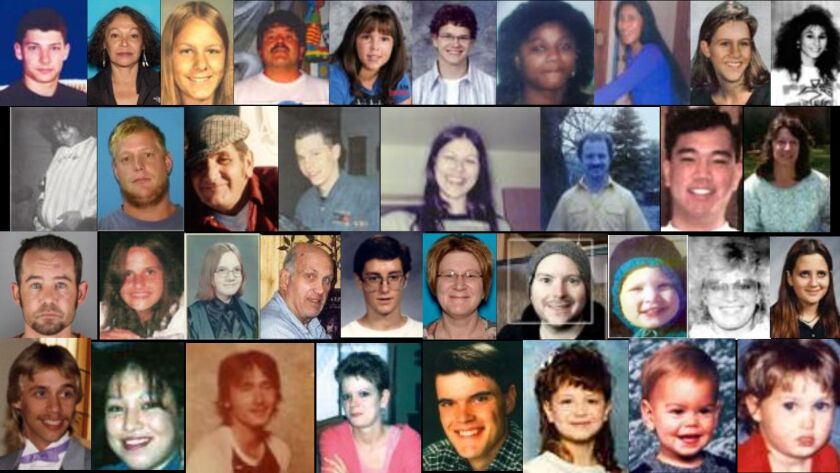

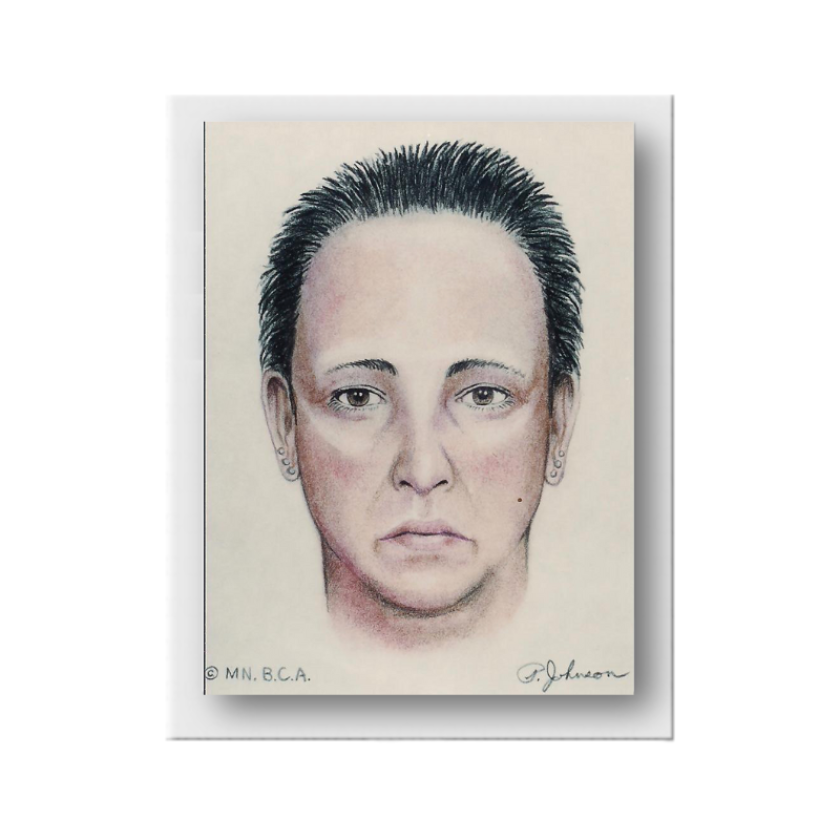

According to the Bureau of Criminal Apprehension's missing-person poster, Jamie is described as a 5-foot, 9-inch white male weighing 120 pounds with brown hair and blue eyes.

The 12-gauge Remington shotgun (with serial number A442608M) that Jamie was carrying at the time of his disappearance was registered with authorities.

The family also enlisted the help of a well-known psychic, Greta Alexander.

“She had a premonition on a well site on an island that was kind of down in that area,” Jim said. “This was probably a month or month and a half after. We flew over there and checked that island out, and I made trips back there. My brother actually hunted back in that area for several years, and I made several trips down there, too, but I don't do that anymore.”

ADVERTISEMENT

That winter, the family called off private search efforts for Jamie.

The hunting shack property south of Jacobson was eventually sold. While Jim no longer hunts in that area, he and his daughter, Gina, have an annual tradition of sitting in a deer stand together during each season’s opening weekend.

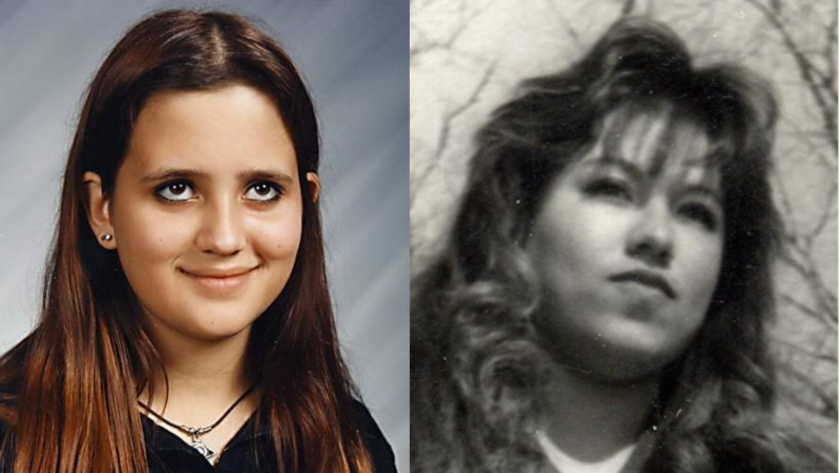

“We drink coffee and eat treats and tell stories as much as we hunt,” Jim said. “Gina has struggled with losing her big brother that she looked up to, but she's turned out to be a very beautiful young woman with a huge circle of supportive friends and a good job.”

Because of Jamie’s past, Jim said there was speculation among some people that his son may have run away, but the thought never entered his mind.

“He was just a fun, adventurous little guy. Loved to try just about anything. He was an outdoors kid. You know — hunting, fishing, camping,” Jim said. “We had no difficulties with Jamie until he got into middle school, and he had trouble with the administration.”

According to a supplemental report by an Aitkin County deputy on the day Jamie was reported missing, his mother stated that when he was 14, he ran away and was found a few miles away in a teepee-type arrangement and seemed quite comfortable.

“My son was a very bright person who liked to press boundaries,” Jim said. “Like any parent-child, when you have a kid that's acting out, you have difficulties. But I would say it was a pretty healthy relationship between the two of us.”

ADVERTISEMENT

Jamie had been placed at Northwest Juvenile Training Center in Bemidji.

After returning to the family home on Pokegama Lake in Grand Rapids, the plan was to have Jamie finish the last few months of high school and graduate with his class.

“But that didn’t happen,” Jim said.

In an Aitkin County Sheriff Investigation Report dated Nov. 1, 1992, an officer had contacted Jamie’s then-girlfriend at the center, who said she had not heard him talking of running away, and she hadn’t heard from him since he disappeared.

Jim firmly believes his son succumbed to the elements, also leaving behind a younger sister, Gina, who was 14 at the time, and mother, Mary Tennison.

“I know a lot of people have been through like circumstances," Jim said, struggling to find the words as he choked up, "and a lot of times it leads to separation and divorce of the parents, and conflicts. In our situation, it didn't do that because my wife never blamed me."

A year following Jamie’s disappearance, a memorial service was held at United Methodist Church. For over a decade, loved ones gathered at the “point last seen” to pay tribute to Jamie.

ADVERTISEMENT

Now, only Jamie’s immediate family gathers each October for a bonfire at their home in Grand Rapids in remembrance of him.

“We still think about him a lot,” Jim said. “You don't come through something like that unscarred, that's for sure.”

While Jamie’s body was never located, a bronze plaque honoring his memory can be found at the family’s plot at Wildwood Cemetery in Cohasset.

To prevent similar tragedies, Jim partnered with the Minnesota Department of Natural Resources to help establish the Jamie Tennison Memorial Compass Fund through the Grand Rapids Area Community Foundation in 1994.

The program receives support from various community partners, including the Itasca County Chapter of the Minnesota Deer Hunters Association. Jim estimates at least 60,000 compasses have been distributed in Itasca County since the program’s inception at a cost of over $100,000, though those numbers are outdated.

In addition to adding survival and orienteering training to firearms safety instruction for youth in Itasca County, students are provided with a compass and brochure of Jamie’s story. Instructors are free to structure the program into their course as they see fit.

“I've had multiple people stop me and thank me and say, ‘You have no idea how many lives this could have potentially saved by all these kids having a compass,'" Jim said.

Anyone with information about Jamie Tennison is asked to call the Aitkin County Sheriff's Office at 218-927-7435.