DULUTH — As far as Roy Hermanson is concerned, a minimum of 50 years in prison was a “bargain sentence” for the man who took the lives of his son and two others at a house party in 1994.

Still, it provided a sense of security knowing that Todd Michael Warren wouldn’t see freedom until at least 2044, at the age of 68, for gunning down Keith Hermanson, Peter Moore and Samuel Witherspoon at an East Hillside home when he was just 18.

ADVERTISEMENT

But now, the victims’ families say they are being forced to relive their trauma as Warren petitions for his release two decades early, on the 30th anniversary of the notorious crime.

“It’s upsetting that this came up,” Roy Hermanson, now 80, told the News Tribune this month. “He killed three young men, all of them about 20 years old. They would’ve had at least 150 years of life left in them. I guess he’s grabbing at whatever to get out, but I don’t think he should ever get out.”

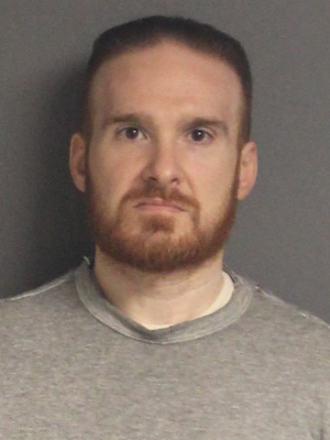

Warren, serving three life sentences for premeditated murder, filed an application this summer with the Minnesota Board of Pardons seeking a commutation of the remaining portion of his court-ordered incarceration.

The 48-year-old said he takes full responsibility for the crime that shocked the city and still resonates with many longtime residents today. But he asserts that he has been humbled by a nearly three-decade prison stay.

“I am no longer the same rash, arrogant boy who resorted to violence to resolve a crisis,” Warren wrote. “Today, I’d reach for a phone, not a gun.”

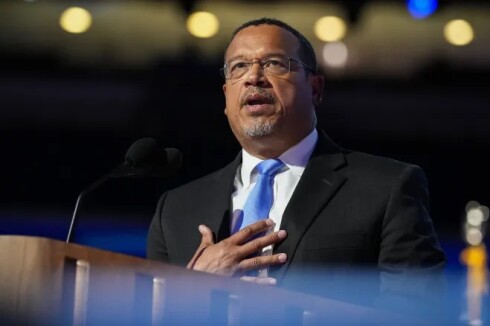

The Board of Pardons — a relatively obscure panel consisting of Minnesota Gov. Tim Walz, Attorney General Keith Ellison and Supreme Court Chief Justice Natalie Hudson — is expected to hear and rule on the application at a meeting Tuesday in St. Paul.

Warren’s request is supported by letters from family, friends and prison associates. But it has received significant pushback from the victims’ families and County Attorney Kim Maki, who called the crime “one of the most grievous in the history of St. Louis County.”

ADVERTISEMENT

“The court recognized then what I urge (the board) to recognize now: That 30 years of imprisonment — a mere 10 years for each life taken — is an unjust and wholly inadequate consequence for the merciless brutality exhibited by Mr. Warren that night,” Maki said.

Victims killed at close range after assault allegations

The essential facts of the case were largely undisputed through the trials of both Warren and a co-defendant — though the teen’s state of mind was a key issue, along with various legal rulings that ultimately led to appeals from both the defense and prosecution.

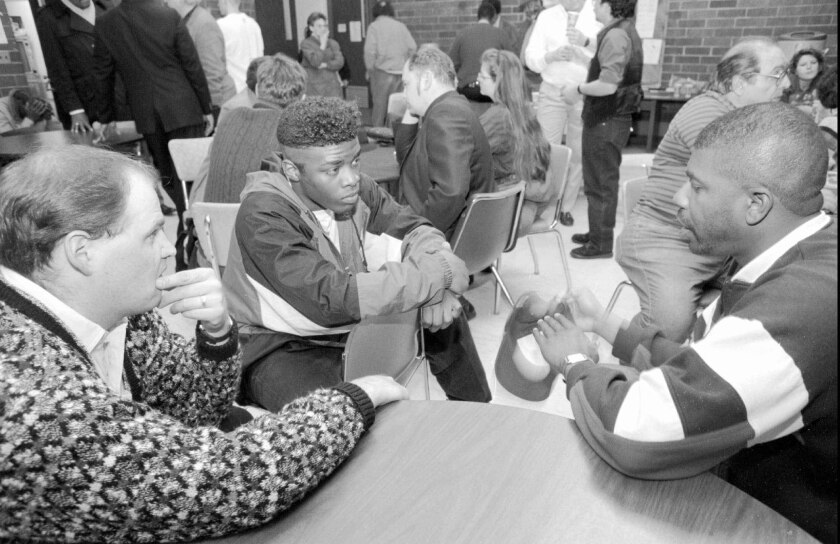

The defendant and all three victims were among many young people at a house party at 816 E. Seventh St. in the early morning hours of March 28, 1994.

Warren, a Proctor High School senior at the time, later testified that he saw his girlfriend’s friend being raped and then found his girlfriend with her clothing partially removed. Enraged, he left with his girlfriend and several other friends, including Doug Towle.

The 18-year-old then drove at least 24 miles to his parents’ home, reportedly making comments about how he was going to shoot whoever was responsible. He retrieved his father’s .44 Magnum revolver and returned to the East Hillside residence.

Inside, witnesses said he shot Witherspoon, who was celebrating his 21st birthday, in the face at close range. He then shot Hermanson, 20, and Moore, 21, who both fell to the ground. Moore denied any wrongdoing and pleaded for his life as Warren fired second fatal shots at both.

Indicted by a grand jury on three counts of premeditated first-degree murder, Warren admitted to shooting the victims but claimed he did not remember many key details. His attorney pursued a heat-of-passion defense, but Judge Galen Wilson ruled Warren could only introduce evidence of the alleged sexual assaults that was known to him prior to the shootings.

ADVERTISEMENT

A Duluth jury in January 1995 found Warren guilty of all three murder charges. Wilson sentenced him to three life terms — but imposed them concurrently, ruling that the defendant could petition for parole after 30 years.

The Minnesota Supreme Court later affirmed the convictions but granted an appeal from prosecutor Mark Rubin, who argued the single sentence failed to recognize the severity of Warren’s actions.

Because Wilson retired by the time the appeals were exhausted, Judge John Oswald presided over the resentencing in 2000. He imposed an unusual combination of sentences — back-to-back-to back life terms carrying minimums of 30, 10 and 10 years in prison.

The structure requires Warren to petition for and be granted parole on three separate occasions before he can be released from custody.

‘There will always be a path for improvement’

Paul Schnell, commissioner of the Minnesota Department of Corrections, provisionally granted parole on the first sentence in 2021.

That means — assuming Warren remains discipline-free and participates in restorative justice programming — he will be eligible to begin serving his second term on March 28.

But he would have to wait until at least 2034 for parole on his second term, and, if successful, 2044 to clear the final hurdle for supervised release.

ADVERTISEMENT

Warren’s clemency application seeks to negate the requirement that he serve the two additional terms.

His request cites his age at the time of the offense, Oswald’s apparent reluctance to impose a stiffer sentence mandated by a higher court, and the fact that his accomplice, Towle, was sentenced to only 11 years for aiding and abetting heat-of-passion manslaughter.

But Warren’s application primarily focuses on his claim that he has “grown out of this tragedy.”

“Through the years, I’ve chosen to help my fellow man, especially young men, as they navigate through the justice system,” he wrote in a six-page letter. “We talk about consequences and ramifications that our actions have, about the interconnectivity of all things. We talk about choosing to live creatively rather than destructively, about taking ownership of our lives, about enriching the lives of others, making better decisions, and putting together concrete plans for successful re-entry into society.

“I will continue to help in any way I can to stop the senseless violence in every community. I have spent nearly 30 years searching for ways to atone for my transgressions and I have made strides, but I know that no matter where I am, there will always be a path for improvement, a path to being (a) better human being.”

Warren is currently at the medium-security state prison in Moose Lake. He has eight minor infractions on file, and none since 2015, according to records obtained by the News Tribune through a data request.

He has completed vocational training in fields including small-engine repair and network cabling, and he has undergone victim-impact and restorative justice programming. He also describes himself as a tutor, mentor and mediator, serving in the prison library and art room, starting a book club and joining a prison writers’ workshop.

ADVERTISEMENT

Warren indicated he has housing and employment prospects if released, but would seek to live away from Duluth “out of respect for the victims’ family and the affected community.”

‘It’s PTSD forever when you kill somebody’

The application, though, has been met with fierce opposition from the families and some authorities.

Peter Moore’s mother, Michele, said Warren deserves neither attention nor leniency.

“The killer needs to stay in prison for killing three people,” she said from her home in Arizona. “It’s pretty obvious. It’s kind of embarrassing, actually, to think that you would let somebody out that killed three people.”

Moore said it does dredge up painful memories, though the grief has been ever-present in the family for the past three decades anyway. She said Warren is “wasting people’s time.”

“It never ends,” Michele Moore said. “It’s just the beginning to a continual cycle. When you murder somebody, you’re a killer for life. It’s PTSD forever when you kill somebody.”

Roy Hermanson, who still lives in Duluth, was brought to tears while discussing his only child’s death. He said others have remarked that he’s never been the same since the killing.

ADVERTISEMENT

“I guess he’s acting within his rights to do what he’s doing,” Hermanson said of Warren. “I just can’t believe that the board would allow it (to be granted).”

Hermanson recalled the initial outpouring of support from the community — an abundance of food, sympathy cards and offers of assistance. But as the attention dried up and the world moved on, a lonely reality began to set in.

Hermanson added that he believes the case would be viewed much differently today. He said his son, who was white, was essentially an “innocent bystander” in a crime that was primarily directed at two men of color, Witherspoon and Moore.

“Those were death penalty actions that he took,” Hermanson said. “There just wasn’t (public awareness of) hate crimes back in those days.”

Witherspoon’s family declined to speak to the News Tribune or submit a formal response to the Board of Pardons. But Maki said she spoke with family members who have struggled with immense distress and depression, finding it too difficult to fully address the application.

Petitions rarely successful, but rules have changed

Receiving a pardon or commutation comes with an uphill battle for anyone actively serving a sentence in Minnesota. In 2022, the board granted only three out of 89 applications in those cases, according to data from the Department of Corrections.

But an overhaul of the process enacted by the state Legislature this spring is expected to increase the number of successful bids.

Minnesota’s unique clemency system long required the governor, attorney general and chief justice to unanimously grant requests. Now, the support of the governor and one other member is sufficient for approval.

The board, which meets twice a year, granted its first non-unanimous pardon in state history in June. Then-Chief Justice Lorie Gildea was the lone dissenter. But she has since retired and been replaced by Hudson, who will participate in her first board meeting.

The board is expected to hear from several speakers, both in support and opposition. Members and their staff have also been provided with at least 124 pages of background information on the crime, court filings, letters and prison records.

Wilson, the judge who presided over the trial and initial sentencing, died in 2018. Current 6th District Chief Judge Leslie Beiers took no position on Warren’s request but told the board: “If Judge Galen Wilson were still living, I believe he would support this.”

Warren’s uncle, Ron Flesvig, said he can understand why the victims’ families “do not see equity in a situation where Todd is not only alive, but lives in freedom.” But he noted any prison release would come with lifetime supervision by the DOC, including a potential return to prison if he ever slips up.

“Todd will continue to live with the memories of his actions on that nightmarish night,” Flesvig wrote. “He will — like all of us — forever live with shame and regret. Being free from incarceration will not free Todd from his thoughts. All any of us can do is to ensure that he spends his remaining years as a productive member of society.”

The county attorney, on the other hand, argued that an early release would “be a miscarriage of justice for the victims, their families and our community.”

“Triple murder cases are exceedingly rare in St. Louis County,” Maki said. “When they happen, they must be treated with the seriousness and gravity they warrant. Life with the possibility of parole might be an acceptable sentence for the taking of one life. It is not acceptable for the taking of three lives, especially in light of Mr. Warren's lengthy premeditation and callous disregard for the victims.”