WABASHA COUNTY, Minn. — A mushroom forager’s 1989 discovery in Wabasha County was the key to unlocking a mystery that began an hour away — nearly seven years earlier.

Deana Patnode was 22 years old when she left the Buckboard Saloon in South St. Paul on Tuesday, Oct. 26, 1982, with a friend, according to the Minnesota Bureau of Criminal Apprehension.

ADVERTISEMENT

That was the last Patnode had been seen or heard from — until a group of three men rummaging for wild mushrooms in a wooded median in rural Wabasha County stumbled on a human skull and bones on May 20, 1989.

The three men promptly reported their discovery, resulting in an ongoing investigation that decades later, through the BCA cold case playing card initiative, revealed the remains belonged to Patnode.

The question surrounding what led her to the wooded median separating Highway 61, five miles south of Kellogg, remains unanswered.

Report of human remains

The Wabasha County Sheriff’s Office, along with the Wabasha County deputy coroner, Michael Walton, arrived at the area where the human skull and skeleton were discovered. After inspecting the area and documenting the scene, they extracted the remains and sent them to Ramsey County for an autopsy.

At the site of discovery, Walton declared the skeleton belonged to a young woman, likely in her 20s, according to a 1989 Winona Daily News story. An off-white pullover sweater was found covering a portion of her bones.

Based on bleaching of the bones and portions of the skeleton buried in the dirt, he estimated they had been exposed to the elements for less than five years.

“The reason it has been there for so long has to do with the fact that it was in the median between two highways, north and southbound, and therefore it is not a place where people are going to go, or animals for that matter,” he told the Winona Daily News.

ADVERTISEMENT

The autopsy report conducted in Ramsey County revealed multiple fractures to her right arm and hip. The injuries were significant, yet weren’t enough for officials to determine a cause of death.

Dental records were cross-referenced with missing persons cases in Minnesota and the surrounding states, yet officials received no matches.

In the wake of the discovery, a BCA artist used the skull to create an image of the unnamed young woman.

While they waited for a lead, Jane Doe’s remains were taken into evidence, and the case went cold — until emerging DNA technology breathed new life into the possibility for answers.

Identifying Deana

The BCA began the cold case playing card initiative in 2008 with the purpose of drawing public attention to the state’s cases that had gone under the radar for years.

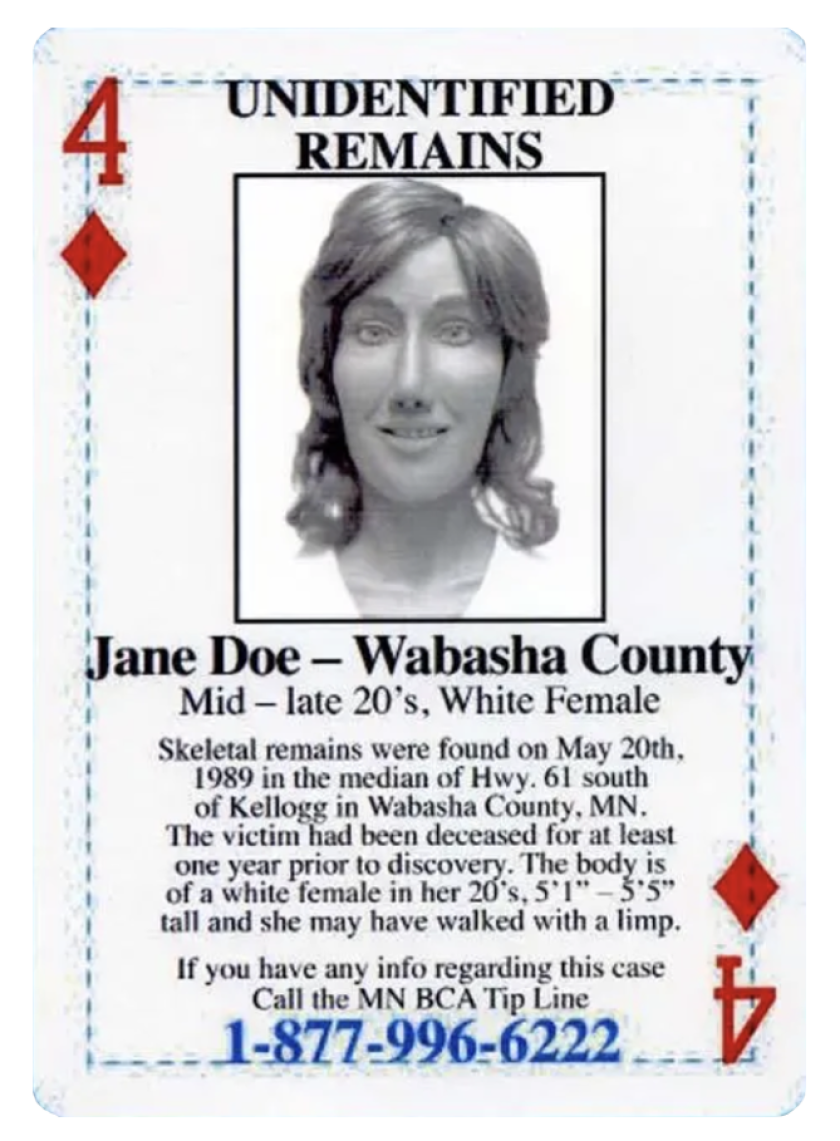

Each card included the victim’s image and a brief description of their case. For unidentified remains, the BCA worked with Louisiana State University’s FACES Lab to create clay facial reconstructions.

The image constructed from the skull discovered in 1989 in rural Wabasha County was used on the playing card for Jane Doe of Wabasha County. She was described as a white female in her 20s who may have walked with a limp.

ADVERTISEMENT

Less than a year after the playing cards were distributed to the public, the BCA received an email from a man who drew a connection between Jane Doe of Wabasha County and a former neighbor who went missing in 1982: Deana Patnode.

Mike Doherty had always wondered what happened to Patnode, who lived near his grandma when he was a child, according to an interview with CBS News. When he saw the playing card depicting Jane Doe of Wabasha County, his began to put the pieces together.

The key to the puzzle was the line stating she may have walked with a limp. Doherty recalled that Patnode had, in fact, walked with a limp as a result of a motorcycle accident.

Doherty’s tip led investigators down a DNA path to discovery. They collected DNA samples from her family members — and, through testing, were able to confirm the remains belonged to Patnode.

The discovery answered one question: Where Patnode ultimately ended up after she was last seen in October 1982. Uncovering her identity left one gaping hole investigators hope to soon fill: What happened to Patnode — and who was responsible?