LITTLE FALLS — With the sky-high costs of flying today, it may be tempting to go it alone and take to the friendly skies by piloting a plane.

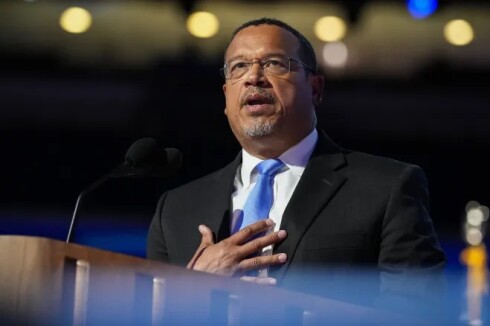

That would have been A-OK with famed aviator Charles A. Lindbergh. who as a boy on a farm in Little Falls during the First World War who dreamed one day of taking to the skies himself.

ADVERTISEMENT

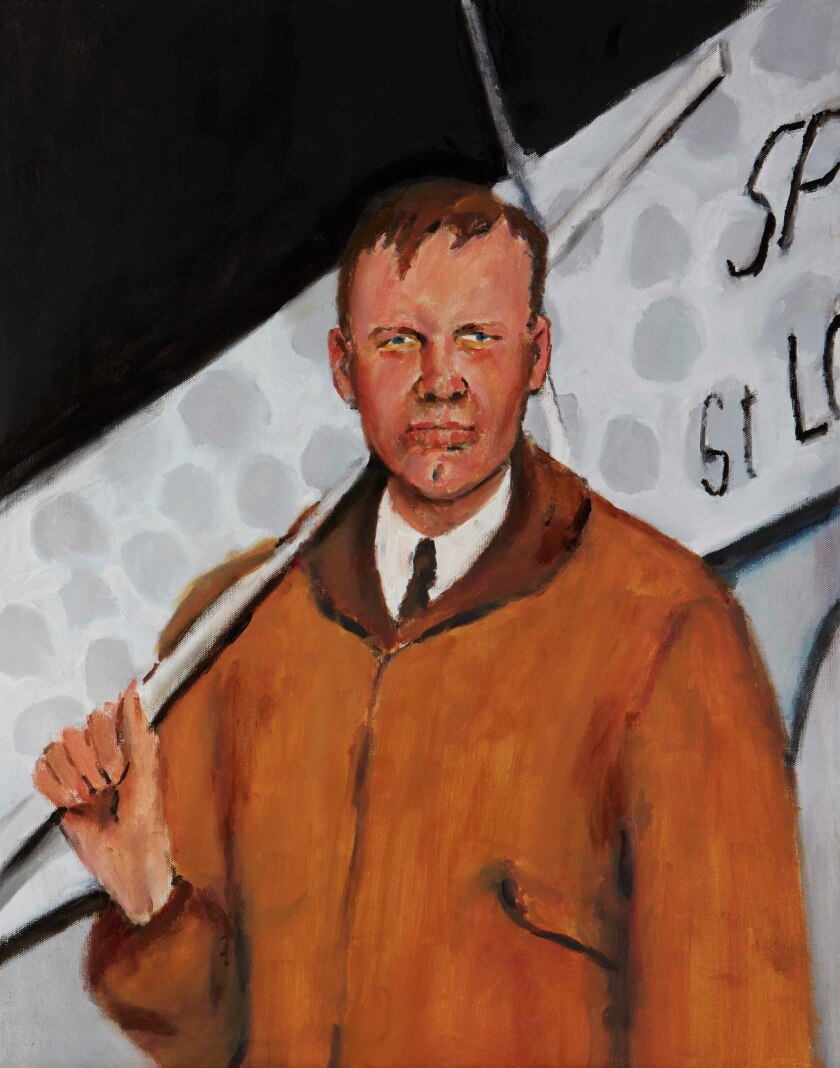

Lindbergh made history by flying nonstop and solo across the Atlantic Ocean from New York City to Paris in 1927. Next month will be the 95th anniversary of that incredible journey.

“Lucky Lindy,” as he came to be known, gained worldwide recognition for that then-remarkable achievement, succeeding where others before him had failed and paid the cost with their lives.

"Lindbergh, a young airmail pilot, was a dark horse when he entered a competition with a $25,000 payoff to fly nonstop from New York to Paris,” according to History.com.

Little Falls upbringing

Lindbergh, the son of a prominent U.S. Congressman, ordered a small monoplane, configured it to his own design and christened it the “Spirit of St. Louis” in tribute to his sponsor, the St. Louis Chamber of Commerce, according to the history-based website.

“In addition to being a skilled aviator, Lindbergh was also an amateur scientist, inventor and leader in the early conservation movement,” according to the Charles Lindbergh House and Museum across from the Charles A. Lindbergh State Park, about a mile south of Little Falls.

“Science, freedom, beauty, adventure: what more could you ask of life? Aviation combined all the elements I loved,” Charles Lindbergh wrote in his book “The Spirit of St. Louis.”

ADVERTISEMENT

Lindbergh was born in his mother’s hometown of Detroit but relocated to a new home in Little Falls on the banks of the Mississippi River on a 110-acre farm outside of town. The farm was also home to Charles's two half-sisters from his father’s first marriage, Lillian and Eva.

“He would often spend his days swimming in the river, climbing trees, interacting with the lumberjacks who brought logs down the river and hunting with his father,” according to the Charles Lindbergh House and Museum.

Little Falls’ favorite son saw his first airplane while growing up in the Morrison County city.

“One day I was playing upstairs in our house on the riverbank. The sound of a distant engine drifted in through an open window. … No automobile engine made that noise. ... I ran to the window and climbed out onto the tarry roof. It was an airplane!” he recounted in his book.

Airmail pilot

Robertson Aircraft Corp. was one of five companies in 1925 to obtain a U.S. airmail contract, according to the Smithsonian, and among its stable of pilots was a 23-year-old Lindbergh, who received flying instructions at a Nebraska flying school from veteran airmail pilot Ira O. Biffle.

On Friday, April 15, it will be the 96th anniversary of when Lindbergh first flew the airmail on that Chicago-to-St. Louis route after the Robertson Aircraft Corp. successfully bid to secure the government contract for the service.

“Lindbergh earned his nickname, ‘Lucky Lindy,’ years before his trans-Atlantic flight. While flying the mail for the Robertson brothers, Lindbergh was forced to bail out of his mail plane not once, but twice!” according to the Smithsonian.

Lindbergh turned his attention to the Orteig Prize for the first aviator to fly nonstop across the Atlantic from Paris to New York or New York to Paris. Raymond Orteig, a French-born American businessman, announced the competition for the $25,000 prize in 1919.

“On Sep. 15, 1926, French flying ace René Fonck and his crew attempted to take off from Roosevelt Field in New York, only to crash at the end of the runway, killing two of the four crew members,” according to the Charles Lindbergh House and Museum.

ADVERTISEMENT

Upon reading about Fonck’s failure, Lindbergh began to plan his own flight to Paris, figuring that "a nonstop flight between New York and Paris would be less hazardous than flying mail for a single winter."

The weight of the airplane was a primary concern for the fledgling daredevil, who wanted to make the trip across the Atlantic by himself and reportedly told Ryan Aeronautical Co. chief engineer Donald Hall that "I’d rather have extra gasoline than an extra man."

“Everything that was too heavy was left behind, including a parachute and radio,” according to the Charles Lindbergh House and Museum.

Making history

The 25-year-old Lindbergh landed his airplane at Le Bourget Aerodrome in Paris on May 21, 1927, after taking off from Roosevelt Field on Long Island, New York, about 33 hours and 30 minutes earlier and 3,610 miles away.

“His greatest challenge was staying awake; he had to hold his eyelids open with his fingers and hallucinated ghosts passing through the cockpit,” according to History.com.

Charles Lindbergh facts

- His father was a U.S. Congressman. When Lindbergh was 4 years old, Minnesota’s Sixth Congressional District elected his father, Charles August Lindbergh, to the U.S. House of Representatives.

- He worked as a daredevil and stunt pilot. After learning to fly at the Nebraska Aircraft Corporation in Lincoln, Lindbergh spent two years as an itinerant stuntman and aerial daredevil.

- He wasn’t the first person to make a transatlantic crossing in an airplane. Lindbergh’s major achievement was not that he was the first person to cross the Atlantic by airplane, but rather that he did it alone and between two major international cities.

- He experienced hallucinations and saw mirages during his famous flight. Between his pre-flight preparations and the 33.5-hour journey itself, he went some 55 hours without sleep.

- He helped invent an early artificial heart. By 1935, Lindbergh had developed a perfusion pump made of Pyrex glass that was capable of moving air and life-giving fluids through excised organs to keep them working and infection-free.

Source: History.com

ADVERTISEMENT

FRANK LEE may be reached at 218-855-5863 or at frank.lee@brainerddispatch.com . Follow him on Twitter at www.twitter.com/DispatchFL .