GRAND FORKS — Even among 1970s activists, the practice of “pieing” opponents of the gay community was controversial.

Detractors described the pie-throwing practice as “bad guerilla theater,” and claimed it cheapened the growing gay liberation movement in the U.S. Some added that it garnered sympathy for those targeted, and also that it risked alienating the general public.

ADVERTISEMENT

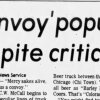

Proponents, however, believed there was power in turning bigots into a spectacle and a laughing stock. By 1977, at least three anti-gay activists had already received pies in the face from members of the Minneapolis-based LGBTQ+ group Target City Coalition. Anita Bryant was, perhaps, the inevitable next target.

In the 1970s, Bryant was, to many, the face of anti-gay sentiment in America. She was a popular singer-turned-spokeswoman for the Florida Citrus Commission and the face of its well-known orange juice ads. She was also a woman on a mission to end “the disintegration of the American family.”

In 1977, Bryant organized a successful and highly-publicized campaign to repeal a Dade County, Florida, law that made it illegal to deny job and housing opportunities to LGBTQ+ people. She called her platform the “Save Our Children” campaign, and hoped it would be the beginning of a movement.

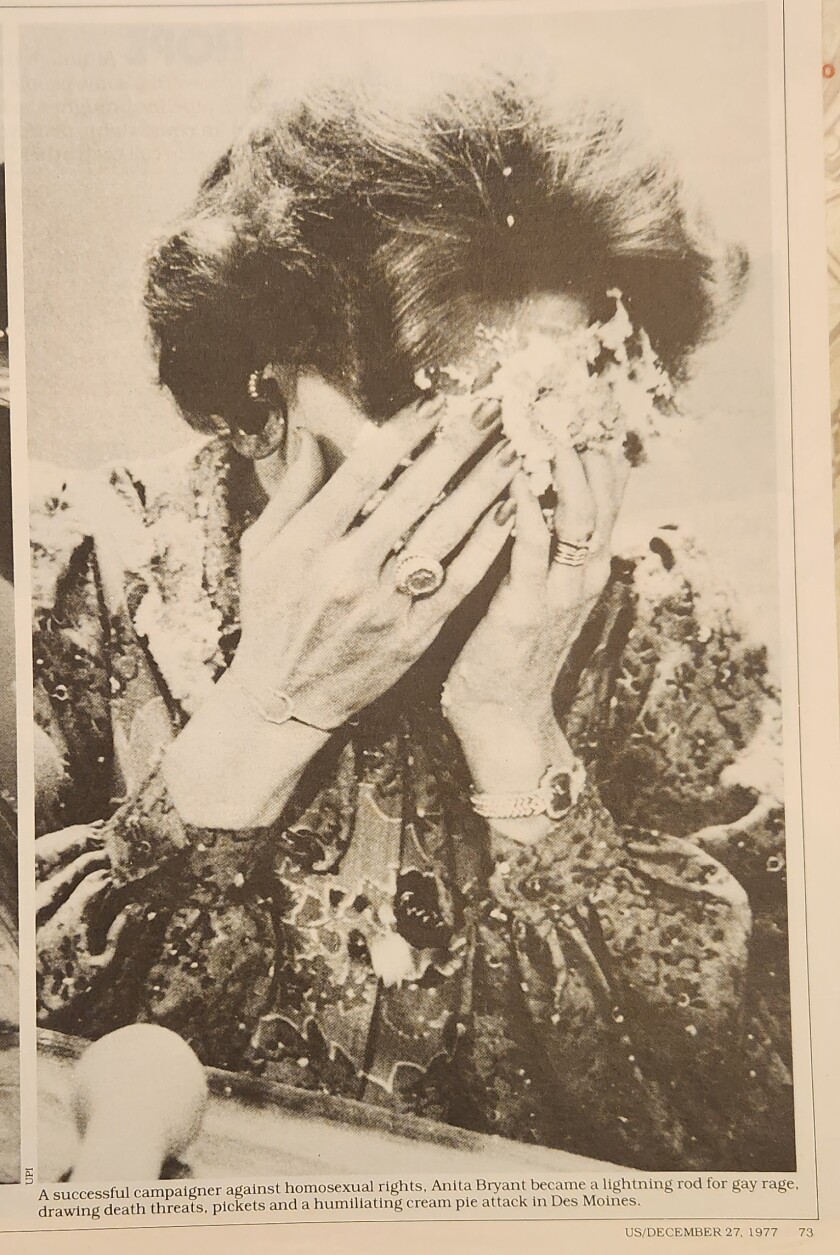

On Oct. 14, 1977, during a live national television press conference in Des Moines, Iowa, where Bryant planned to speak about her recent political victories, came a reckoning: Thom Higgins, a young gay activist from the Twin Cities, aimed for a spot four inches behind Bryant’s nose and threw a banana cream pie into her face.

There were gasps and shutter clicks as cameras spun to face Higgins, who stood with his hands in the air.

“Well,” Bryant quipped, wiping cream filling from her eyes, “at least it’s a fruit pie.”

The singer began to pray, and then began to sob.

ADVERTISEMENT

As Higgins left the room, he turned to Bryant.

“Thus always to bigots,” he declared.

The next day, the moment was splashed in headlines across the country.

“Anita hit: Singer gets a pie in the face, then prays for the thrower,” said The Houston Chronicle.

“Anita Bryant runs out of town after protests,” read the New York Post.

“The Gaycott Turns Ugly,” The Nation reported.

“Is a Pie-in-the-Face Really Violent?” the TV Guide asked.

ADVERTISEMENT

“This is the year of the pie,” Higgins told reporters after the incident. “I saved her a bullet. The pie thing relieved a lot of anger that gays feel towards her. … It left another bigot with a sticky face.”

The moment seems to be widely regarded as the beginning of the end of Bryant and her crusade. She continued her press tour across America, but never really achieved the same momentum. She was fired from her lucrative Florida Citrus Commission contract in 1978, and fell further out of public favor two years later when her husband divorced her. She filed for bankruptcy in 1997, and since then has faded to the footnotes.

In 2024, LGBTQ+ history appears to remember the pieing of Anita Bryant favorably.

But for Higgins’ friends from his days at the University of North Dakota, any cultural or political impact the pieing may or may not have had isn’t really what they remember about the incident.

“We just thought it was funny,” said Mike Jacobs, Higgins’ former classmate at UND. He and every other person interviewed for this story laughed at the mention of Bryant – several said they had forgotten about “the Anita Bryant thing.”

“Pieing Anita Bryant,” crowed another friend, Pat Carney. “Hilarious!”

When Higgins threw the pie in Des Moines, he had already established himself as a prominent gay rights activist in the Twin Cities. But even during his UND days, the way his friends and classmates remembered it, Higgins had always been a bit of a rabble-rouser.

ADVERTISEMENT

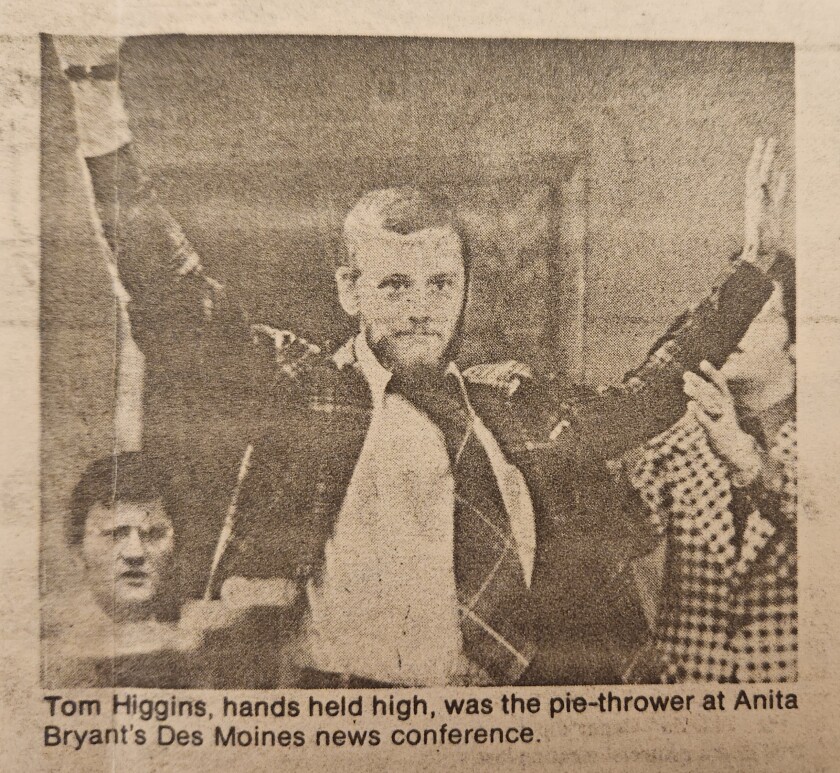

His love of challenging people he believed needed to be challenged had a tendency of getting him into trouble. He was thrown out of the University of North Dakota as a freshman in 1968 for his involvement in an underground newspaper called the Snow Job, which excoriated Greek Life on campus.

‘He liked to be a troublemaker’

In 1967, the war in Vietnam felt very close to Grand Forks. At the time – in Carney’s memory – North Dakota was likely one of the largest nuclear superpowers in the world, due to its large Air Force bases in Minot and Grand Forks. Carney said it resulted in a pipeline to Thai marijuana.

Meanwhile, energies at UND were frenetic.

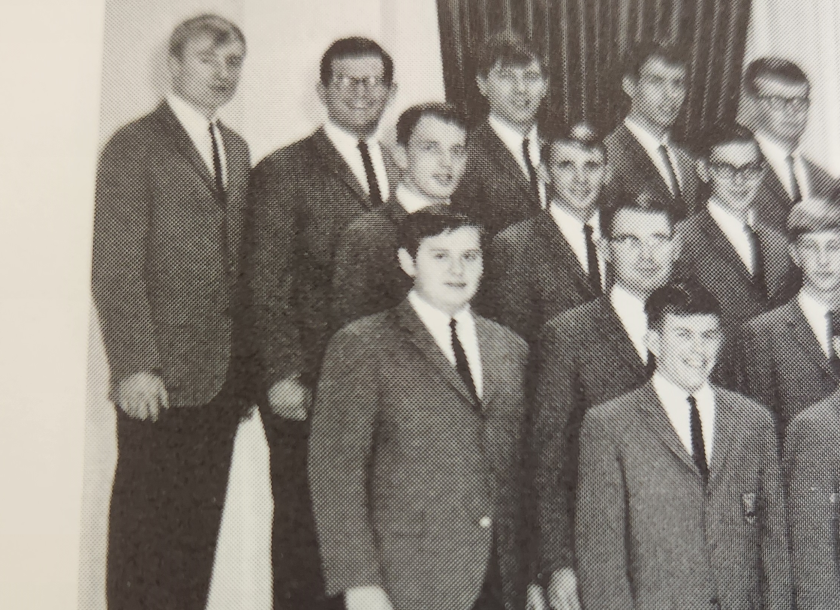

Higgins, who grew up in St. Paul, arrived on campus as a 16-year-old journalism and theater student, admitted through a program for gifted high-schoolers. The political divide on campus was stark, and Higgins was openly anti-war, but he never identified as a hippie, said Carney, a former photographer for the Dakota Student, UND’s student newspaper. As a teen at UND, Higgins was clean cut, and known for walking around campus in a suit with a vest and ascot. He was involved in Catholic student groups, and had little interest in drinking, at least as far as Carney remembered. Although not exactly out yet, Higgins’ sexuality was never a secret.

Those who moved in Higgins’ circles in Grand Forks agreed that, at a time when there was no shortage of colorful characters on the UND campus, he was memorable.

He was “ebullient,” said Lyn Burton, a former editor of the Dakota Student. He was the kind of person who would breeze into a friend’s kitchen the morning after a party, put on a pot of coffee and start making everyone eggs, she recalled.

“I never knew him to knock on a door, because every door that he opened was always open to him,” she said. “You’d definitely invite him to your parties.”

ADVERTISEMENT

Jacobs and Chuck Haga – both former Dakota Student editors – stared thoughtfully at each other as they searched for the right words to describe their former classmate. Proud, maybe? Not arrogant, necessarily.

Not everyone agreed.

“He was super arrogant,” Carney said. “And kind of a pain. … He was sure that he was God’s gift to journalism.”

Carney and Higgins were friends and remained in touch until Higgins’ death in 1994. During their shared time at UND, Carney remembered Higgins as an “instigator” and an enthusiastic prankster. Once, Higgins and Carney and other friends sneaked into the hotel of an opposing athletic team in the dead of night to hang an antagonistic banner. Another time, after conservative student groups took issue with the Dakota Student’s anti-war stance and decided to protest by removing the newspapers from campus, Higgins, Carney and others hatched a counteroffensive. The group hid near the students’ van, and as the conservative students loaded papers into the vehicle, Higgins and his friends stole the papers back one ream at a time to redistribute on campus.

During the fallout from the Snow Job, Higgins was the only student who was suspended because, in Jacobs’ memory, he pretty clearly was the leader – but also, Carney said, because Higgins was the only student who admitted his involvement.

“He didn’t fess up — he was proud of what he did. That’s the difference,” Carney said. “If you said, 'who in the hell caused that riot?' He would be the first to say, ‘oh, that’s me.’ He liked to be a troublemaker.”

The Snow Job

Not everyone remembers the Snow Job incident that way.

ADVERTISEMENT

Based on interviews conducted and documents reviewed for this story, the Snow Job appears to have been universally regarded as in poor taste.

At the time, one school official called the paper “the most vulgar and obscene publication he has seen during his 10 years here,” according to minutes from a UND committee meeting convened to discipline the students involved. But Carney said that today, by modern standards, there aren’t many people who would clutch their pearls over the Snow Job.

“It’s really funny what is scandalous now compared to what was scandalous then,” he said.

Although Jacobs estimated there were probably 30 organizations on campus that could just as well have been the target of the Snow Job, the women of the Alpha Phi sorority were the ones who received the brunt of the satire. Greek Life had reached new heights at UND in those years, and Alpha Phi in particular had a reputation for being self-selecting, Jacobs said. He believes Higgins likely felt like he was punching up.

“They saw themselves as the epitome of Greek Life,” Jacobs said. “They thought that they should be looked up to.”

Official disciplinary proceedings began when the president of Alpha Phi filed a formal complaint with the university.

Meeting minutes show that Higgins said if the Snow Job had been allowed to die a natural death, the scandal would have blown over in days. Jacobs agreed that if the sorority hadn’t pushed back, the Snow Job likely would have become just another outrageous thing that happened at UND in the ’60s.

“But they did push, and they pushed with strength,” he said.

One of the women had a family member who was an important state official with the resources to punish the university. Jacobs said the official did complain, but he doesn’t believe he ever tried to take any action.

“But the Alpha Phis saw themselves as powerful, because they had connections,” Jacobs said. “They saw themselves as powerful enough to take revenge.”

Higgins ultimately admitted to the committee that he wrote two stories for the Snow Job.

There was some argument in favor of expelling Higgins altogether – but ultimately, the committee unanimously voted that Higgins should be suspended for the remainder of the school year and be required to submit evidence of receiving psychiatric counseling before being readmitted.

The committee agreed there wasn’t enough evidence to punish other students who were allegedly involved. There was a motion to suspend a second student – Bruce Pennington, who was allegedly seen stapling copies of the Snow Job in the Dakota Student office but denied his involvement – but the motion did not get a second.

(Pennington, recalled by several sources interviewed for this story as one of the only other known gay students at UND in those years, went on to become an influential gay activist in his own right. His 2003 obituary printed in the Washington Post credited him with founding one of the first gay radio programs in the country.)

In the aftermath of the Snow Job, Higgins was fired from the Dakota Student and the Dakotah Annual. He was openly stung by the severance from both organizations, “his two most important extracurriculars, because his major is journalism,” meeting minutes say. The documents also noted that because he had been invited to stay at the university following his involvement in the program for gifted high school juniors, the now 17-year-old Higgins did not have a high school degree.

According to the documents, Higgins told the committee “he wished he never got involved with the Snow Job.”

A March 17, 1968, Herald article about Higgins’ suspension quoted him saying he was “unjustly suspended” and that he intended to sue the university to force it to reinstate him as a student. It’s not clear if he ever actually attempted legal action against the school.

Following his suspension, Higgins moved back to the Twin Cities. He never returned to UND.

“I mean,” Jacobs said, “why would he?”

Activism

In June 1969, one year after Higgins left UND, the gay liberation movement in America started with the Stonewall Riots in New York City. It was a watershed coming-of-age moment for people of Higgins’ generation, Burton recalled. In a 1977 article in the North Dakota Star – a newspaper published by the UND journalism department – Higgins told a reporter that around the same time, after moving to Minneapolis, he began living openly as a gay man.

After graduating from UND, Carney spent several years traveling the country working as a photographer, but settled in the Twin Cities in 1977. It wasn’t long before he ran into Higgins again.

“First of all, he had come out. And he had had a growth spurt,” Carney recalled. “He was this big, strapping, handsome guy with the biggest laugh you’ve ever heard in your life.”

Since leaving UND, Higgins had found work, at different times, as a copywriter, a staff writer, and as manager at a variety of gay establishments.

At the same time, he had become highly involved in a push for equal protections for LGBTQ+ people. He was a founding member and officer of FREE, an LGBTQ+ activist group. When he was fired from his job at the Minnesota Services for the Blind after telling his supervisor he would appear in a press conference to advocate for gay rights in 1970, FREE organized the first public gay rights demonstration in the state, according to the Minnesota Civil Liberties Union.

Higgins was involved in campaigning for a number of openly gay political candidates. He was also involved in a number of legal disputes on behalf of LGBTQ+ people who claimed they had been discriminated against, and testified in favor of protections for LGBTQ+ people before the Minnesota Legislature. He also worked extensively with the Positively Gay’s Cuban refugee task force, helping to resettle gay refugees.

In his younger days, to the occasional irritation of many of those around him, there wasn’t an argument or a fight Higgins wouldn’t participate in, Carney recalled. As he got older, his energy didn’t subside, but he did get wiser about where he used it.

“He was more businesslike in his activism,” Carney said. “He was always good at pranks – pieing Anita Bryant was one – but he wanted results. … I was always surprised – like, ‘wow, Thom. You’ve grown up.’”

In the late 1970s, Higgins began caring for a neighbor who was terminally ill with cancer, and in the early 1980s, Higgins was inspired to go to nursing school to become a caregiver, the woman’s son, Anthony Trelles, told the Herald.

At the same time, AIDS had begun decimating gay communities across America. Burton said she believes Higgins’ decision to become a nurse and his commitment to his community were intrinsically linked.

“HIV/AIDS was beginning to kill our friends,” Burton said. “It was dreadful. We didn’t have the vaccines. It was horrible. Just absolutely horrible. … It’s hard to explain now, how terrifying HIV/AIDS was in the ’70s.”

Death

Sometime in the twilight of the 1980s, Carney got a call from Higgins.

“I said, ‘hey Thom, how you doing?’” Carney recalled. “And he said, ‘Well, I’m living with my mother, and I’m dying.’ As matter-of-fact as if he had joined a baseball team.”

Higgins approached his death the same way he seemed to approach everything else in life, Carney said.

“It was another project,” he recalled. “The projects were, OK, we’re going to move. We’re going to work on this campaign. I’m going to die.”

Both Carney and Burton said that at the end of his life, more than anything, Higgins seemed nostalgic. Burton said he seemed like he was trying to find meaning by retracing his steps, as if trying to find a way to quantify the impact he had and the difference he made.

Burton recalled the last time she saw him. A few months before his death, they met for lunch. She said she didn’t know he was sick until he told her, but noticed right away that he was very thin, “to the point of almost gone.”

“He wanted to kind of talk about the old days,” Burton said. “You know, did I remember ‘X’ or did I remember ‘Y,’ and he wanted to talk about the Snow Job.”

And he wanted to talk about Anita Bryant.

“It was, in some ways, a celebratory high watermark of his younger days,” she said. “I mean, it was both an act of defiance and an act of courage. And yet, somehow in keeping with that puckish sense of humor. I mean, he didn’t hit her with anything that would hurt her, except her pride, and her designer dress.”

Higgins died on Nov. 10, 1994, at the age of 44, due to complications from AIDS. He would have been 74 last week, on June 17. Before he died, he collected his life’s papers and donated them to the state of Minnesota. They can be viewed at the Minnesota History Center in St. Paul.

“I think he made a difference in the life of anyone that came into his orbit,” Burton said. “He was an attractor. People who come within the orbit are touched.”

“I remember him in two ways,” Carney said. “As an annoying little fat kid at the University of North Dakota, and then as this amazing character in the gay community in Minneapolis. He was both of those, and it was a pretty positive remembrance.”