SIOUX FALLS, S.D. — A desolate ravine in the western section of Sioux Falls, South Dakota, has hoarded the secret of Lt. Naomi Kathleen Cheney’s murder for nearly 82 years.

It was within the ravine that investigators found nearly all of the evidence related to Cheney’s murder, a crime that ended up including at least two suspects and tens of thousands of people questioned, with some even strip searched.

ADVERTISEMENT

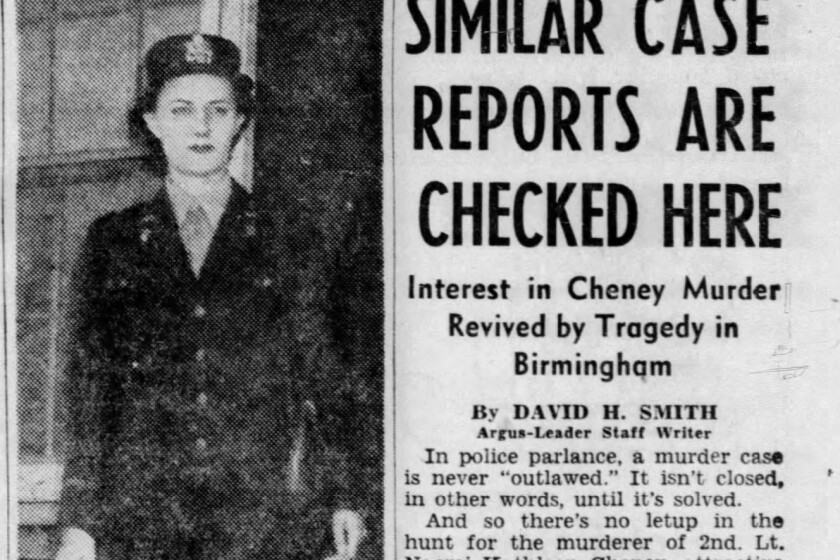

Soldiers, nearby residents and soothsayers were investigated by the military and by the Sioux Falls Police Department, which spent years trying to solve the mystery that began on Oct. 5, 1943, during the height of World War II, when Cheney, a 25-year-old lieutenant in the Women’s Army Corps, or WAC, disappeared.

At first, military personnel thought she had gone AWOL.

Called “one of the most attractive WACs in our camp” by Lt. Luther Evans, an assistant public relations officer at the Army Air Force radio school, Cheney was last seen around 9 p.m. by a gate guard at the Sioux Falls Army Air Field after she visited another WAC officer at the school hospital, according to the Argus Leader.

A stranger to the area as she grew up near Jasper, Alabama, Cheney asked the guard if it was safe to walk home alone. The guard, according to newspaper reports, told her to use her own judgment.

She most likely chose a shortcut — a walk along railroad tracks — on her way home, according to newspaper reports.

She was never seen alive by anyone else but her murderer again.

The next day, 10-year-old Val Rae found Cheney’s battered body in the ravine.

ADVERTISEMENT

“One side of the face reddened by a hemorrhage, the hair matted with dried and darkened gore, one eye sealed shut and the ears, nostrils and mouth filled with caked blood,” the Argus Leader reported in 1945.

“The dead WAC officer lay, face upward, in a weedy hollow south of the bridge, about 40 feet southwest of the railroad tracks and just below a cabin camp at the west end of the bridge and on the south side of the street,” the Argus Leader reported.

A trail of blood led from her murder site to a cabin, about 50 feet away. A suspect was found there, but investigators struggled for definite proof.

Her father, Frank E. Cheney, a veteran of the Great War, or World War I, joined the U.S. Navy three days after his daughter’s death and issued a statement to the press.

“I am going to do my best to fill a niche in the armed services, a niche that Kathleen filled while she lived. She would want it that way,” Frank told reporters with the Lead Daily Call in Leads, North Dakota.

Frank Cheney described his daughter to journalists as: “Always a studious child and athletic; jolly yet serious at any sort of work. Energetic and with plenty initiative. Too venturesome perhaps but serious and careful as a rule withal. She loved the WAC and the army.”

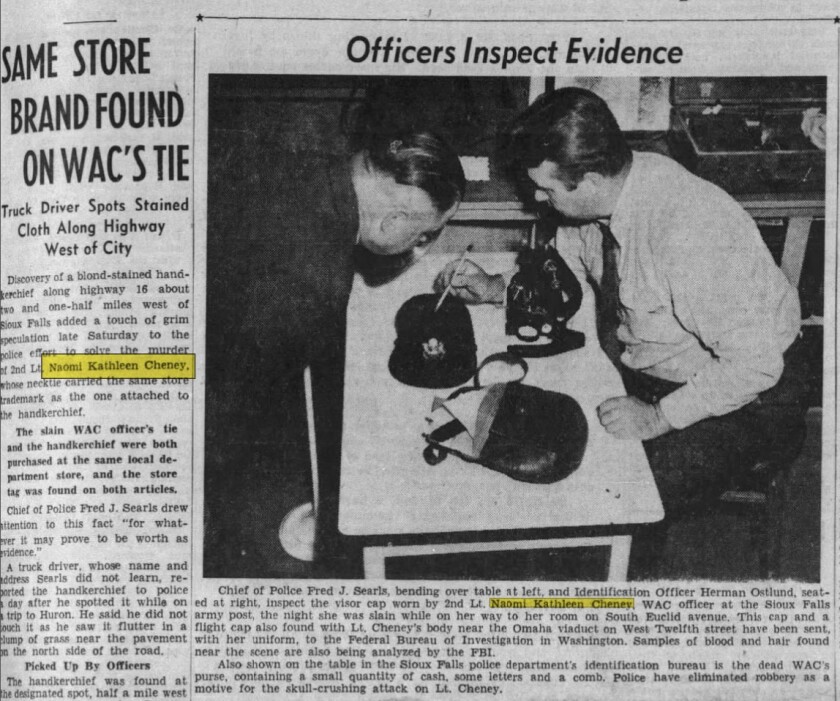

Mystery surrounded the case, and army investigators were “wholly without clues” as to who the killer was, according to the Argus Leader, who also reported that Cheney's murder is the city's oldest cold case . There was no evidence of robbery, as cash was still inside her purse, or of rape, according to authorities at the time. By Oct. 10, military investigators turned the case over to the Sioux Falls Police Department.

ADVERTISEMENT

“Their strongest hunches proved to be taunting will-o’-wisps. An eerie hush still grips the gloomy, forbidding dell, and a mocking wind sighs through the gnarled trees and brush that imprison a shocking secret,” the Argus Leader reported two years after the murder in 1945.

The clues

As soon as young Rae reported her discovery of Cheney’s body, military investigators and policemen swarmed the scene, trampling the area in search of clues: the blood trail; a bloody handkerchief; her cap and flight hat and purse — which was not rifled with — and evidence she put up a struggle, were the only clues they found. The police response at that time ruined, scattered and eliminated “what bits of evidence might have been left among the grass and twigs,” the Argus Leader reported.

The search for her killer “ extended to every scrap of garbage and piece of paper ” found in the area, according to the Argus Leader.

The Army conducted the “greatest mass examination in history” by checking the backs of 40,000 hands from all enlisted soldiers in the area, according to the Evening World-Herald. Several thousand soldiers were also forced to strip so their bodies could be examined for marks.

The day after Cheney was murdered, the blood trail led to one suspect who was arrested. There was blood on his shoes, blood inside and outside the cabin, according to newspaper reports. He was a 31-year-old transient farm worker from an unnamed Iowa town who arrived a week before the murder and was taken into custody as he was preparing to leave the camp, according to the Argus Leader.

Throughout his three-week-long incarceration, police refused to release the suspect’s name, saying only that he was married with two children. He was about 6 feet tall, was “fairly good looking,” with black hair and a black mustache, and was staying at the cabin where suspicious blood and hair was found, Sioux Falls Police Chief Fred J. Searls told reporters at the time.

ADVERTISEMENT

In his possession, he had a draft registration card, the Argus Leader reported.

Disagreement

A coroner’s jury determined that Cheney had been murdered, despite disagreement between two doctors. One doctor believed she had been run over by a car while the second doctor theorized she had been beaten to death, possibly kicked by someone with heavy shoes, according to news reports.

Searls chose to work the theory that Cheney had been murdered by “tremendous force,” according to the Argus Leader.

The difference of opinion between the two doctors still pointed to the inescapable fact that Cheney died from multiple fractures of the skull and brain hemorrhaging.

“There has been no evidence that the death was caused by an automobile. If Lt. Cheney had been struck by a car, there would have been marks on her somewhere in addition to those on her head,” Searls told reporters for the Rapid City Journal.

ADVERTISEMENT

Suspects

Although Searls sent the handkerchief, Cheney’s uniform and cap, as well as blood and hair samples to Federal Bureau of Investigation headquarters in Washington, D.C., for examination, 1940s technology could not provide an accurate enough match to convict the unnamed suspect, who joined the Army and was later killed while fighting overseas.

“The analysis can’t tell if the blood on the handkerchief and the tie is from the same person, but it can tell if the blood is of the same type,” Searls told the Argus Leader at the time.

In January 1944, the murder of a 68-year-old woman named Agda Moline in Omaha, Nebraska, brought Cheney’s case back into the news. Searls sent the police department in Omaha the complete unsolved case file — thicker and heavier than a mail-order catalog — saying that both murders strongly resembled each other.

“Both women were beaten about the head and dragged to a place of concealment. In each case mystery of the assailant has not been solved,” the Rapid City Journal reported.

Moline disappeared while waiting for the bus after dropping her son off at a railroad station as he left to return to military service, the Omaha World-Herald reported on Jan. 11, 1944.

The first real clue in Moline’s case came when detectives found her emptied purse on a rooftop in Omaha on Feb. 3, 1944, according to the Omaha World-Herald. One of the detectives, Robert Green, fell from the roof, injuring his leg.

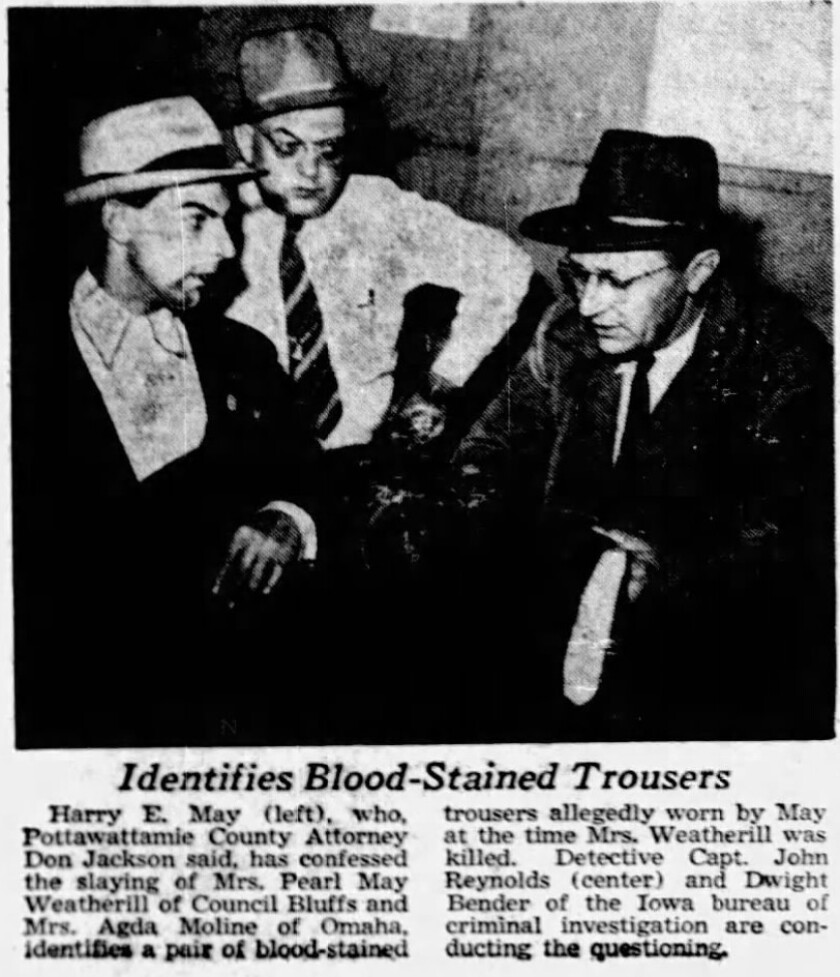

Police charged a 23-year-old man named Harry E. May with Moline’s murder after he confessed to the murder of another woman, the Evening World-Herald reported. They tried to get him to confess to Cheney’s murder, but May later said he was forced into a confession.

ADVERTISEMENT

“I told of killing an Omaha woman and hitting her with a brickbat, but that was a lie, too,” he said. “They told me as long as I had killed one woman, I might as well have killed two [women].”

May, a one-time inmate in an Iowa state mental hospital, reportedly strangled a third woman, Mae Weatherill of Council Bluffs, Nebraska, on Mother’s Day, according to the Omaha World-Herald.

May was eventually convicted of Weatherill’s murder, but not of the murders of Moline and Cheney. He was sentenced to 30 years in prison, according to the Evening World-Herald. During the trial, the courtroom was standing room only, but as District Judge Charles Roe pronounced May’s sentence, only three people were present.

Investigators from Sioux Falls also traveled south to Arkansas, Tennessee and Georgia to interview fortune tellers and spiritualists because of leads that showed Cheney “had faith in them,” Searls told reporters in 1943.

The investigators weren’t asking them to look into the future, or into the past, but wanted to know if Cheney had ever voiced any fears that might offer a clue into the identity of her slayer.

Three of the investigators wanted to know if there was any “grudge motive” from her hometown in Alabama, and they all returned to South Dakota empty-handed.

The father

By 1949, Cheney’s case had still not been solved, although a news story published in the Daily Argus-Leader reported her case wouldn’t be closed until it was solved.

Interest in Cheney’s case was revived after her 53-year-old father, Frank B. Cheney, a postal clerk after the war, shot a woman to death, wounded her husband and 11-month-old son, and then killed himself in Alabama in October 1949, according to the Daily Argus-Leader.

A domestic dispute began between Floyd Greer, his wife, Hazel, and Frank Cheney and his wife, after turning on a gas stove to provide heat for a sick child. Cheney, dressed only in his underwear, woke up from a nap and opened fire on Greer, the Birmingham News reported.

“An enraged veteran of two wars pumped six bullets into a woman, wounded her husband and baby, shot at two ambulance men and then killed himself in a wild pistol spree here yesterday morning,” the Birmingham News reported on Oct. 17, 1949.

“The first shot grazed my neck and he evidently turned the gun immediately on my wife and started pumping bullets into her body,” Greer told reporters with the Birmingham Post after the incident.

Greer was wounded in the shoulder and neck, and his son, Chris, was struck on the right arm. Both were treated at a local hospital, according to the Birmingham News.

Greer ran with his baby — who was sickly — into the yard and cried for help. When police arrived, he turned to go back into the house and “heard a muffled shot.” Cheney had turned the gun on himself, according to the Birmingham Post.

“The last time I saw Hazel was the split second before the flash when she screamed to warn me that Mr. Cheney had a gun,” Greer told the Birmingham Post.

Unsolved, but still open

In January 2025, the case remained open but inactive, Sioux Falls Police Department Spokesperson Sam Clemens told Forum News Service.

“All investigative leads have been exhausted and there’s nothing more detectives can do unless new information is found,” he said.

Cheney’s police case file is still considered confidential, however, and will not be released to the public, Clemens said.