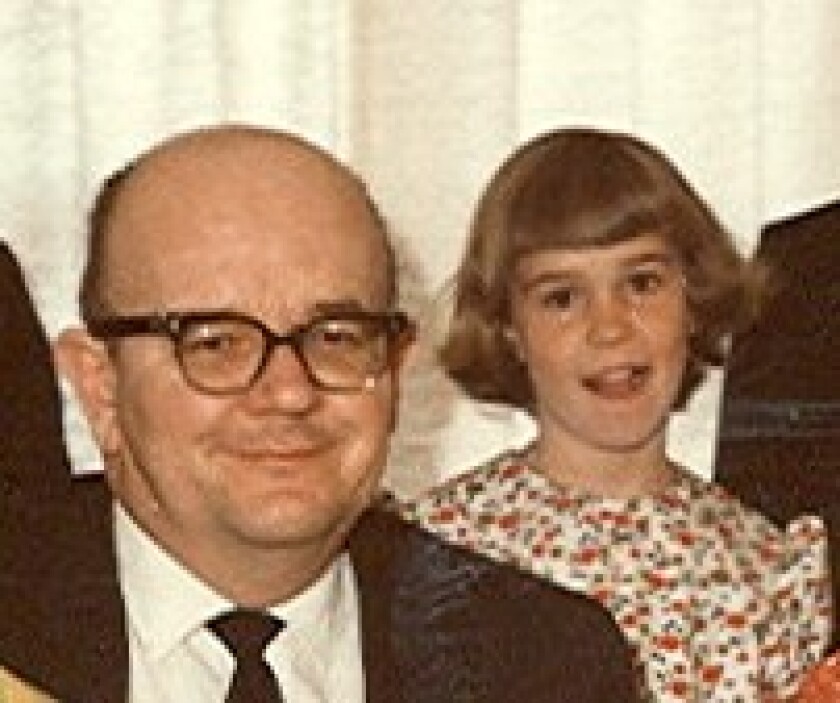

CHOKIO, Minn. — A few years ago, following the death of her father, Julie Stillwell Sorenson and her mother, Donna, were going through some of her father’s belongings. Among the trinkets, mementos and documents, which told the story of his life, was a newspaper clipping that brought back a powerful memory.

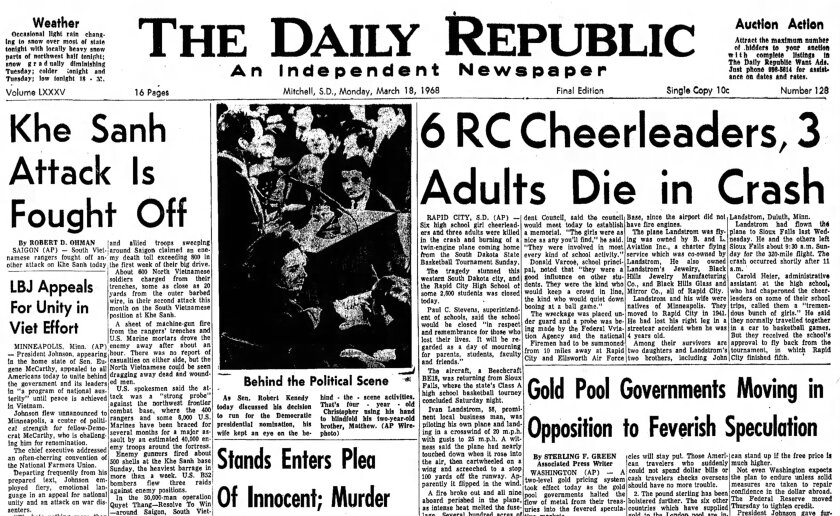

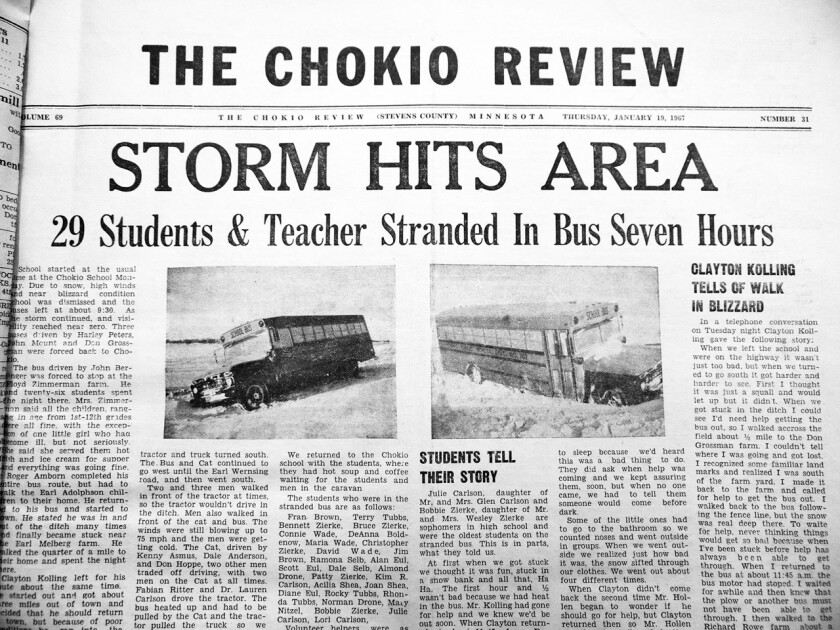

It was The Chokio Review from Jan. 19, 1967, with a headline in big bold print that read “STORM HITS AREA.” The subheadline provided more detail: “29 Students & Teacher Stranded In Bus Seven Hours.”

ADVERTISEMENT

“Closing my eyes, I shivered, recalling the many times in my childhood when I sat with my siblings in the living room, listening to Dad sharing stories with friends and families. This story was most-requested on dark, blizzardy afternoons,” Sorenson recalled.

The Chokio Bus Rescue of Jan. 16, 1967, is legendary in the small Minnesota town 20 minutes west of Morris — a day when schoolchildren narrowly escaped death thanks to townspeople who risked their own lives to save them, including Larry Stillwell, Julie’s father.

Sorenson, now living in Moorhead, figured the story her father first told more than 50 years ago was worth a retelling. She did just that on her website with the help of the teachers, students and heroes who were there.

"I am really shocked that more people don't know about this event,” Sorenson said. “ Because there are quotes from people who said ‘by the time we got to them, those kids wouldn't have lasted much longer.’ That’s a real startling thing to say.”

The storm

The weekend of Jan. 14-15, 1967, was unseasonably warm for Minnesota. With a high of 31 degrees, it was just below the freezing mark. (According to weather reports in 1967, the average high temperature for that day was around 16 degrees.)

It was still in the 20s when children got ready for school on Monday morning, Jan. 16. But that was about to change thanks to a fast-moving blizzard underestimated by forecasting equipment at the time.

“It was balmy weather,” Sorenson said. "So everybody got to school, but as soon as they barely got to school, they turned the buses around within half an hour or so. They sent everybody back home.”

ADVERTISEMENT

Snowfall started light, but visibility was worsening, with winds blowing over 75 mph. Temperatures plunged to 10 degrees below zero, with dangerous wind chills making it feel even colder.

By 9:30 a.m. six buses pulled out of the school parking lot to send the children back home. Some wouldn’t get far.

Three buses turned around almost immediately. Conditions were that bad. The children from those routes were sent to their assigned storm homes in Chokio. (Some rural communities had people who lived in town sign up to be ‘storm homes’ to host farm kids who were stranded in town because of the weather.)

A fourth bus driven by Roger Amborn dropped all of his riders safely home, the last two of whom he had to pick up and carry to their front door. When he tried to make it home himself, the bus repeatedly went into the ditch. Amborn walked a half-mile to stay at the Earl Melberg farm for the night.

The fifth bus driven by John Berlinger was forced to stop at the Floyd Zimmerman farm. He and the 27 students spent the night there.

But 29 other students and one teacher weren’t so lucky. They were stuck on the sixth bus and stranded for seven hours in a life-threatening blizzard.

Stranded

Sorenson, now 63, was attending kindergarten in a neighboring town in 1967. However, she interviewed several students who were on the bus that day for a firsthand account of what happened.

ADVERTISEMENT

According to reports, the bus was only about three miles from town when it went off the road and got stuck. It was 10:30 a.m.

“The front was lower than the back of the bus. And the right side was tipped into the ditch. So the bus was off-kilter,” Sorenson said. “So the kids couldn't even sit on the left side of the bus, they all had to sit on the right side of the bus.”

According to a story in The Chokio Review, driver Clayton Kolling made an effort to get the bus out of the ditch but was unable to do so. He left the bus running as long as he could to keep the students warm. But the motor died around noon. And the bus started getting dangerously cold.

Julie Carlson was a sophomore, and together with Bobbie Zierke, also a sophomore, they were the oldest students on the bus.

“At first, when we got stuck, we thought it was fun, stuck in a snow bank and all that. The first hour-and-a-half wasn’t bad because we had heat. But when the bus motor stopped, we knew it was getting serious,” she said.

She said one of the worst parts was the bus sitting at an angle.

“The snow started shifting in the bus on the seats and melted and ran onto the floor, forming a glaze of ice, making it impossible to walk. We had little girls jumping on the seats of the bus to exercise to keep warm,” she said.

ADVERTISEMENT

Carlson said the older kids took care of the younger ones.

“They were wonderful. They did what we told them to do and didn’t cry or fuss,” she said. “ We didn’t let anyone go to sleep because we’d heard this was a bad thing to do. We just had to keep telling them help was coming soon.”

Carlson said the older kids also took the younger kids outside to go to the bathroom.

“We’d go outside in groups,” Carlson said. “When we went outside, we realized just how bad it was — the snow sifted through our clothes.”

As the afternoon went on, the bus was getting colder and the students were getting hungrier. Most had eaten their sack lunches shortly after they stalled. The older students said they tried not to show fear to the younger kids, but some were losing hope.

“I remember we older children were writing notes to family, thinking we weren’t going to make it,” said Starr Botcet, who was 13 at the time.

ADVERTISEMENT

Getting help

Most school buses back then were not equipped with two-way radios, so shortly after getting stuck in the ditch, bus driver Kolling knew he’d have to leave to get help.

Fortunately, teacher Arnie Hollen was on the bus to supervise the children who would stay behind while he walked to a farm a half-mile away. (Hollen was said to have taken off his winter coat and used it to cover some little girls who were wearing patent leather shoes and tights.)

Despite knowing the area well, Kolling got lost in the whiteout conditions. Eventually, he made it to the farm to call for help and walked back to the bus with blankets and candy for the kids.

“When he returned with the blankets and candy, we all cried. We were so happy to see him and know he was safe. This really renewed our spirits,” Carlson said.

“The bus driver walked three times to different farmsteads to get blankets and to use the phone,” Sorenson said. ”And back in those days, they had party lines. So everybody knew exactly where the bus got stranded.”

Kolling was communicating with school officials to let them know what was going on. They sent out snow plows, but they, too, were getting stuck.

That’s when some men in the community jumped into action.

ADVERTISEMENT

“They got together at the Co-Op and got the vehicles that were going to have to lead the buses out. They actually had men with ropes leading the tractors, because otherwise, the tractors would drive right in the ditch, because they couldn't see,” Sorenson said.

Larry Stillwell was one of the men on the rescue crew, taking on the backbreaking work in subzero temperatures and frigid winds up to 75 mph.

“They could only be out there a few minutes, so they would take turns grabbing that rope and leading the power vehicle out front to keep it out of the ditch and get it down the road,” Sorenson said.

Student Laurie Marlow remembers seeing the rescuers tied together by rope, leading the vehicles between the ditches.

“I also remember the image of the men, 13 of them I believe, who walked out to us, forming a human chain from fence line to fence line,” Marlowe said.

Rescued

The students were rescued and taken back to school, as it was getting dark. Student Julie Carlson said they were hungry and cold.

“When I got to the restroom, ice was frozen in my hair,” she said.

She recalls the school superintendent Burton Nypen meeting them at the door.

“There must be an awful weight on your heart to have to make these kinds of decisions,” she said. “We used to joke that for a while if there was a flake of snow in the air, we would be sent home from school.”

Nypen was grateful to the men who brought the students safely back to school, according to Kevin Asmus, the son of rescuer Kenny Asmus.

“Dad said Supt. Nypen was so excited to see the children arrive at the school that Nypen walked over to my Dad and kissed him right on the lips!” Kevin said.

The students were fed hot soup at school and then paired up with storm homes. The next day, the media attention started. The Associated Press called, and students Julie Carlson and Bobbie Zierke were interviewed on NBC’s “Today” show.

“It even made international news,” Sorenson said. “Somebody had a friend in Germany, who heard the news on German TV.”

The day was difficult, but many look back now with nostalgia. That’s perhaps understandable for the students stranded at storm homes for what some described as “big slumber parties,” especially the busload of kids stranded at the Floyd and Dorothy Zimmerman home.

Son Curt Zimmerman remembers it well.

“It was exciting at first,” he said. “It’s a big old farmhouse, so we had room. I remember the piles of shoes on the floor. Piles and piles of shoes! The coats were heaped on the beds.”

Zimmerman said people sometimes wonder how they fed everyone.

“Back then, people had a full pantry,” he said.

Sorenson noted in her blog, “Coincidentally, a traveling frozen food truck had stopped at the farm earlier in the day and Dorothy had stocked up on wieners, ice cream and other food.”

For breakfast, everyone was fed pancakes, eggs and sausage.

According to Curt Zimmerman's sister Marcia DeNeui, the parents of the kids stranded at her home were so grateful they gave Floyd and Dorothy a pair of sweaters as tokens of their appreciation.

“They wore those sweaters for many years,” Curt said. “They wore them until they were practically worn out. Mom and Dad felt very proud of them.”

However, even those students stranded on the cold bus hold onto positive memories of the community that pulled together to rescue them.

Bitterness and blame were kept at a minimum. Most parents expressed gratitude to the rescuers for saving their children and to bus driver Clayton Kolling for his efforts walking four miles during the freezing blizzard to get help and bring back blankets.

While her family moved away from Chokio a few years later, Sorenson still admires the grit of the people in her former hometown of Chokio.

“It's just such a neat community. It's so strong. They take care of each other. They're just good people,” she said.

Sorenson said by digging deeper into the bus rescue she first heard about during childhood storytime, she learned more than she ever imagined.

“I learned the strength of community is a real thing. It's something that doesn't happen by accident. That communities work at being a community and it's a conscious decision. So that when there's a time of crisis, they don't have to build the support they need. It's there when they need it.”

If you’d like to read Julie Stillwell Sorenson’s full blog post about The Chokio Bus Rescue of 1967, email her at julie@juliesorenson.com for a free downloadable copy.