CHISHOLM — When a small plane nosedived into an Iron Range lake in 1977, killing two FBI agents, authorities offered little explanation.

The men were merely “conducting routine investigations out of the Duluth office,” the FBI claimed at the time, according to a brief report in the Aug. 26 edition of the Duluth Herald.

ADVERTISEMENT

For decades, that was the accepted story. And, after a few days, the incident was virtually forgotten, the agency never disclosing why two Minneapolis-based agents were flying over the rural area north of Chisholm.

The truth, according to a book released more than 20 years later, was so top secret that even the agents’ families didn’t know. In fact, the case they were working on was known only to the president of the United States, his national security adviser and a handful of other federal officials.

The agents, Trenwith S. Basford and Mark A. Kirkland, had been surveilling a University of Minnesota professor who was spying for the Soviet Union, it was first revealed in the 2000 book “Cassidy’s Run: The Secret Spy War Over Nerve Gas.”

“The bureau could not afford to divulge the truth,” author David Wise wrote, “for the crash of the Cessna threatened to unravel the longest-running espionage case of its kind in the history of the Cold War, an extraordinary drama that had begun two decades earlier.”

Double agent exposed spies

The events leading up to the plane crash may sound like a storyline straight out of a James Bond film.

Operation Shocker, as it was known, was initiated by the FBI in 1959 amid heightened tensions and fears of nuclear war with the Soviet Union. It primarily involved the use of a double agent in a bid to deplete Soviet resources and uncover the rival’s intelligence operations in America.

According to Wise’s book, U.S. Army 1st Sgt. Joseph Cassidy was asked to pose as a fake defector, despite having no training in spycraft. He was able to make contact with the Soviets and established a relationship in which he would provide information in exchange for money.

ADVERTISEMENT

The documents Cassidy produced over the next several years were a mix of both real and fake information about the United States’ efforts to develop a nerve gas agent, Wise wrote. The Americans had determined the formula was too unstable to be used in weapons, but hoped the Soviets would waste time on their own research.

The operation reached a new phase, the book explained, when Cassidy was transferred to a base in Florida. Because Soviet diplomats were limited to the area around their embassy in Washington, they were forced to rely on deep-cover spies to carry out the exchanges with Cassidy.

One mole exposed by the operation was Gilberto Lopez y Rivas, a native of Mexico, who was observed by FBI agents accepting documents from Cassidy in Florida on several occasions — sometimes bringing along his wife and young child.

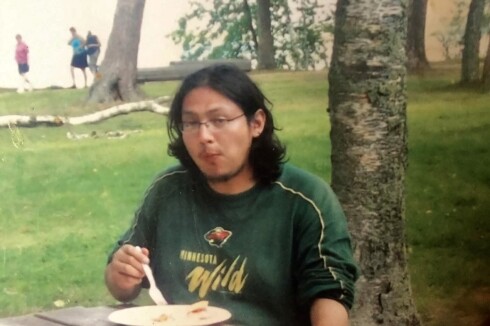

Wise wrote that agents would continue to track Lopez for years, following him as he studied in Texas and Utah, and even deploying a young, Spanish-speaking agent to befriend him. And, in 1976, they followed Lopez north after he was hired to teach Chicano studies at the University of Minnesota.

Plane crashed amid storm

It was around 5 p.m. on Thursday, Aug. 25, 1977, when the Cessna 172 floatplane encountered a sudden summer storm.

At the controls was Basford, 60, an experienced pilot who owned the plane, which had been approved by the FBI for official use. A Minneapolis native, he had worked for the bureau for 35 years and was planning to retire in a matter of months.

His passenger, Kirkland, 33, was the assigned case agent on the Lopez investigation.

ADVERTISEMENT

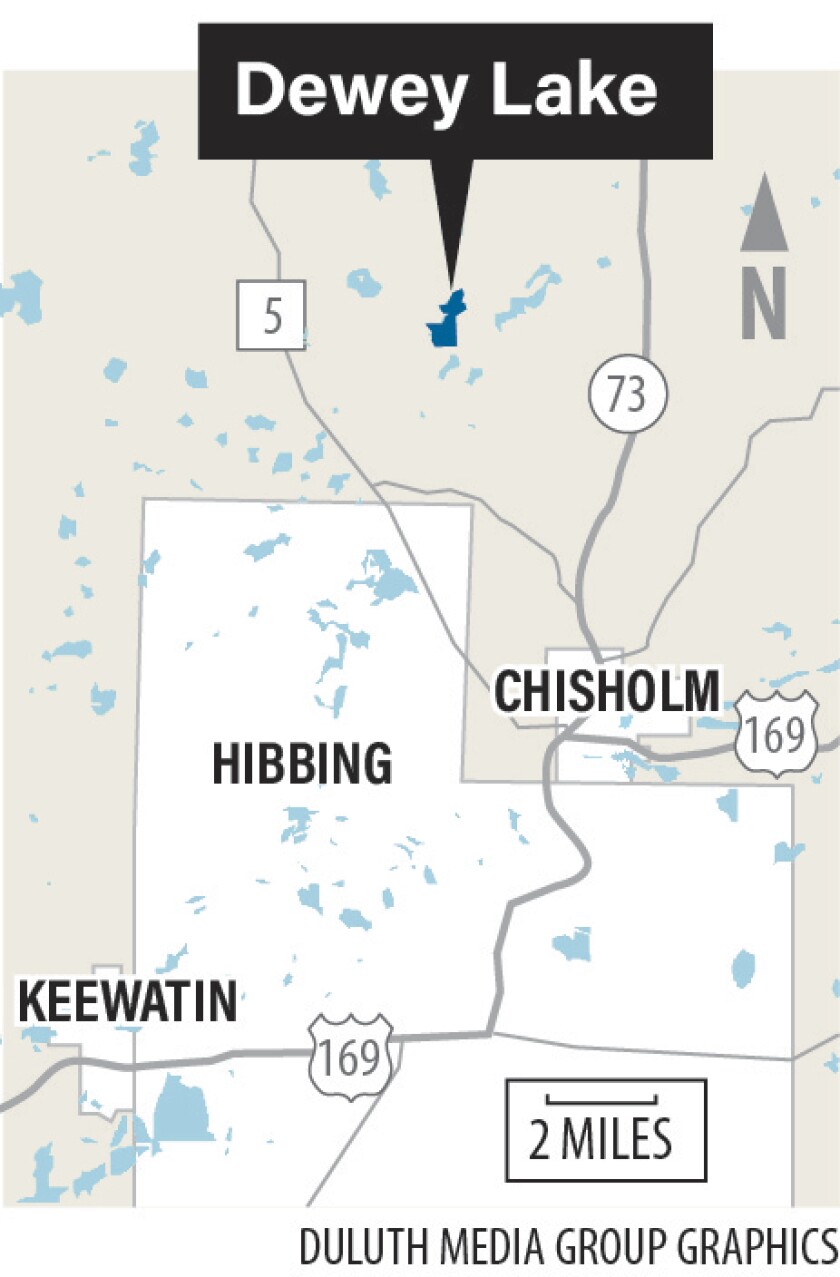

Rain was said to be torrential at the time, combined with strong winds and fog that limited visibility. Basford radioed the Hibbing air traffic tower shortly before the crash, indicating he would land on Sturgeon Lake.

Instead, however, the seaplane crashed in 12 feet of water at the north end of nearby Dewey Lake, about 7 miles northwest of Chisholm. When rescue workers arrived, they found the Cessna in an inverted position with its nose stuck in the mud of the lake bed and its tail sticking out above the surface.

Witnesses said the pilot appeared to be having trouble seeing, aborting two landing attempts before crashing on the third. One reported Basford apparently gunned the motor to avoid some trees or got caught in the wind. Police also took reports from residents who suggested the engine was sputtering.

The two agents were found still strapped in their seat belts, and they were believed to have died on impact.

Both men were married, with Basford having two sons and the younger Kirkland leaving behind two boys and a daughter.

“I do not blame the bureau; it was an act of nature,” widow Tish Basford told Wise years later. “Tren never had to face the ravages of old age, disease and futility. He died in his prime, being useful and doing what he most liked to do.”

While on-duty deaths of FBI agents are rare, the incident never received significant follow-up coverage from the state’s newspapers — almost certainly because of the bureau’s efforts to keep the counterintelligence operation under wraps.

ADVERTISEMENT

One letter-writer to the News Tribune at the time suggested perhaps the bureau was monitoring steelworkers who might be inclined to strike, citing the agency’s troubled reputation following incidents such as the “Chicago Seven” case at the 1968 Democratic National Convention.

But the reality, as unlikely as it seems, is that the Iron Range had been thrust into a decades-long espionage case known only to top government officials.

Truth revealed decades later

The 2000 book first exposed the operation, indicating agents believed the Lopezes were headed toward the Canadian border that day.

“They took some funny trips,” Phillip A. Parker, a former FBI senior counterintelligence official, was quoted as saying. “There were some suspicious activities. Their actions on some of the trips they took to northern Minnesota indicated they were watching for surveillance. But we never saw them clear a drop or meet anyone.”

Still, the Lopezes had been camping nearby, and news of two FBI agents killed in the area could set off alarm bells. Wise wrote that some in the FBI had also been eager to begin arresting the Soviet assets, so Lopez and his wife were confronted by agents in Minneapolis in 1978.

Lopez admitted to spying for the Soviets, according to the account, “because of how the United States has treated Mexico throughout history. And because of the way Chicanos are treated in the U.S.”

Wise wrote that agents hoped to arrest the couple, and perhaps flip them against other spies. But top brass at the Justice Department nixed the idea due to legal concerns.

ADVERTISEMENT

When the couple lived in Texas, agents had installed a secret camera inside a crawlspace above their duplex unit. That was before the Foreign Intelligence Surveillance Act was signed into law establishing procedures for domestic surveillance, and some of the FBI’s actions had not been approved by the attorney general as required at the time.

So, despite the confession, the Lopezes boarded a plane to Mexico City just two days after they were confronted, avoiding prosecution.

By the time “Cassidy’s Run” was released, Lopez was serving as a congressman in Mexico. He maintained his spying wasn’t about a hatred for America or making money, but rather in hopes of spreading a more peaceful style of socialism.

“We don’t regret anything in that historical moment in which we lived,” Lopez told the Associated Press in 2000. “It was an option of struggle. We did nothing of which we would be ashamed.”

Wise, an award-winning journalist who authored several books on the U.S. intelligence community and politics over 50 years, died in 2018.

While the book was not among his most well-known works, he explained in a C-SPAN interview that he spent years working with sources to get the story and felt it was an important story to tell.

“I wanted people to know that the Cold War was not just a video game,” Wise said. “We’re not talking here about Nintendo. This cost lives. In this case, this operation cost the lives of two FBI agents.”

ADVERTISEMENT